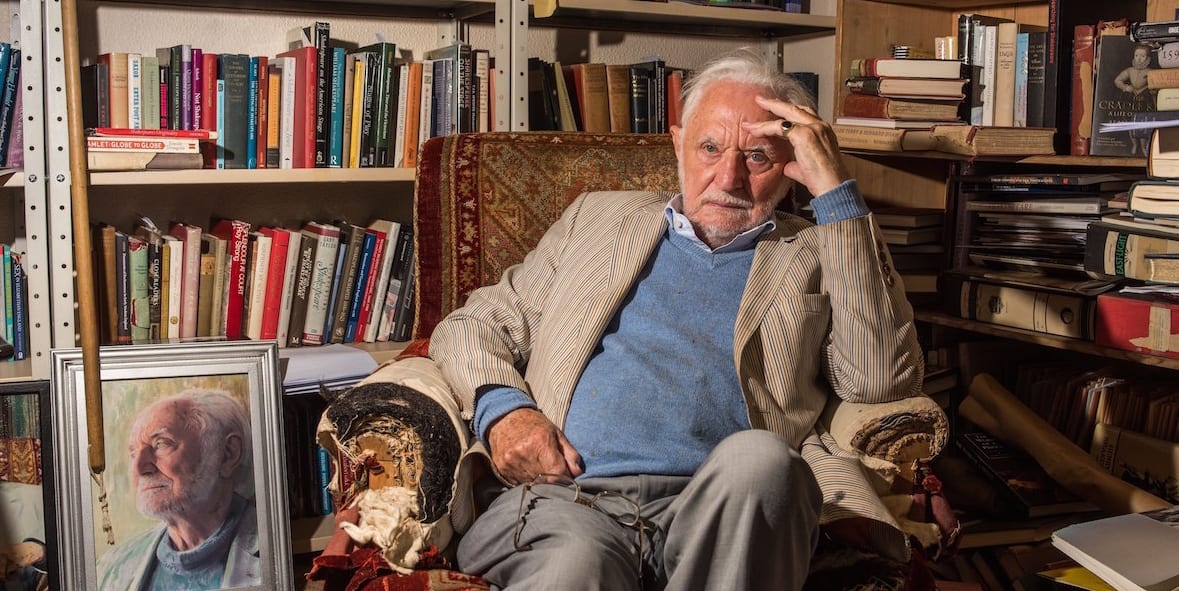

In the Queen’s 90th Birthday Honours Professor Stanley Wells received a knighthood in recognition of his services to Shakespeare scholarship. Today, 21 May 2020, Professor Sir Stanley Wells celebrates his 90th birthday.

He is widely considered to be the world’s foremost Shakespeare scholar.

Due to COVID-19 the following interview was conducted in writing via Q & A format presented to him by Playstosee.com’s reviewers Tim Hochstrasser and Grace Barber.

Professor Wells, how did Shakespeare first enter your life? What are your earliest memories of engaging with theatre and his plays in particular?

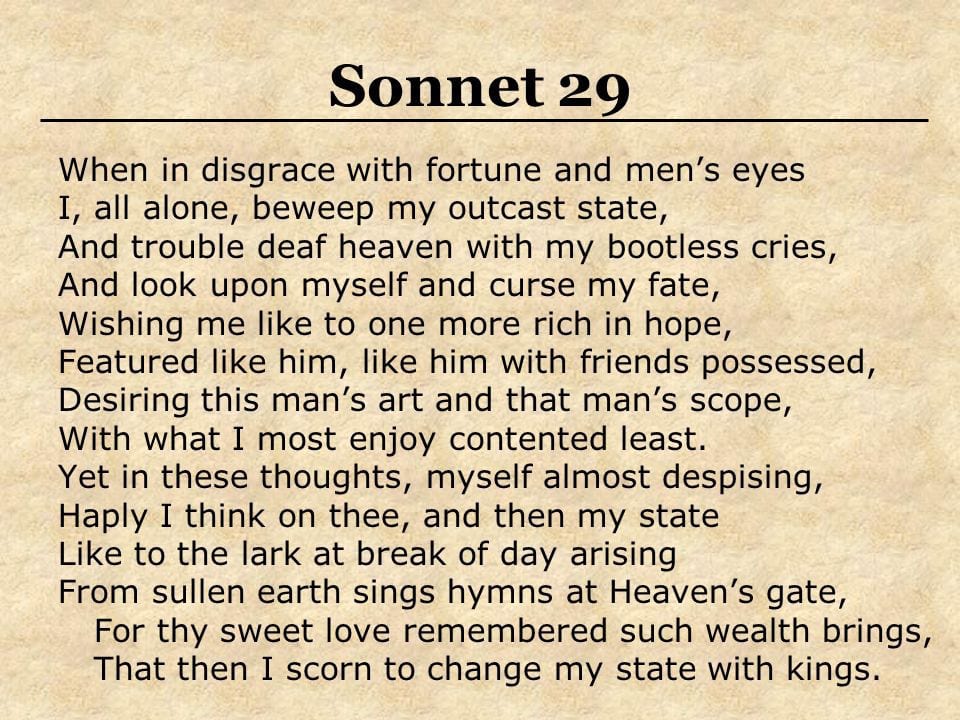

I first encountered Shakespeare when I went to grammar school, in Hull, at the age of eleven. I remember reading the quarrel scene from Julius Caesar in front of the class, brandishing a ruler instead of a sword. I also have an early memory of a classroom reading of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in which I had to read Hermia’s line ‘O hell! To choose love by another’s eyes?’ I felt awkward at having to say the word ‘hell.’ A little further on I read some of the Sonnets and especially liked No. 29 for its celebration of love and friendship. In the sixth form, I had an inspiring English teacher and was deeply moved by classroom readings of King Lear. Also round about this time I saw performances given by Donald Wolfit and his touring company of King Lear and Othello. At the age of eighteen, I went to read English at University College London. There I had fine lectures in the Shakespeare course from Winifred Nowottny and Harold Jenkins. No less important I was able to attend great performances. I saw Laurence Olivier as Richard III, and as Antony with Vivien Leigh as Cleopatra. On my twenty-first birthday, I saw Alec Guinness as Hamlet. It was a great time for Shakespeare on the London stage.

How did Shakespeare then become the focus of your career?

I spent six years as a schoolteacher before going to Stratford-upon-Avon in 1958 to do a PhD, for which I began my career as an editor by editing two short novels by Shakespeare’s early contemporary Robert Greene. At that time, I also taught short courses run by the British Council which involved both, lecturing on the plays and leading discussions of productions.

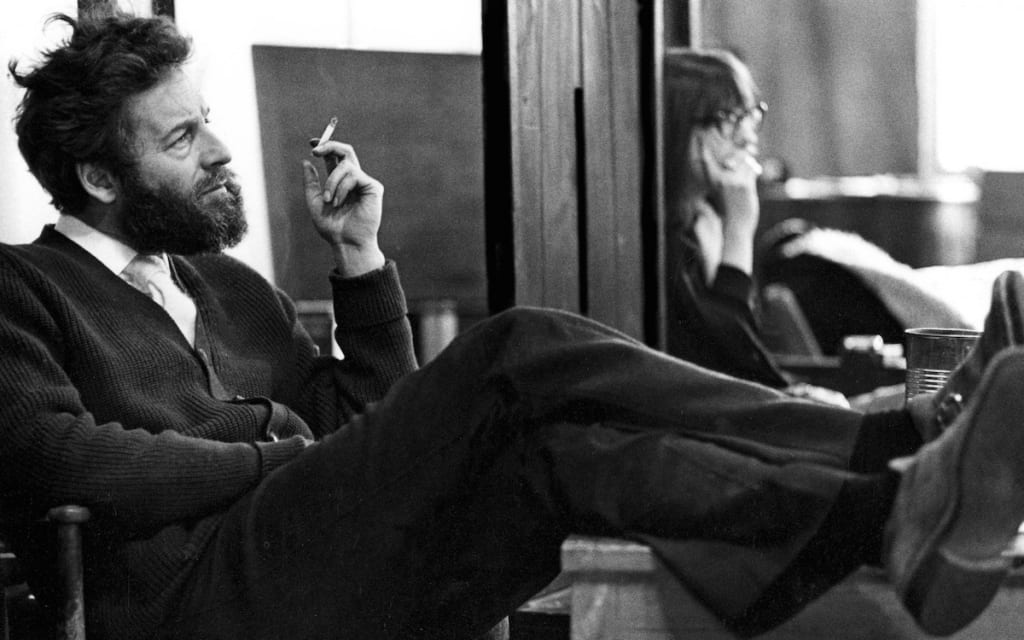

The Director of the Memorial Theatre, soon to become the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, was Peter Hall, soon joined by John Barton. This was all invaluable experience for my later work as a university teacher, a Shakespeare editor, and a reviewer of performances.

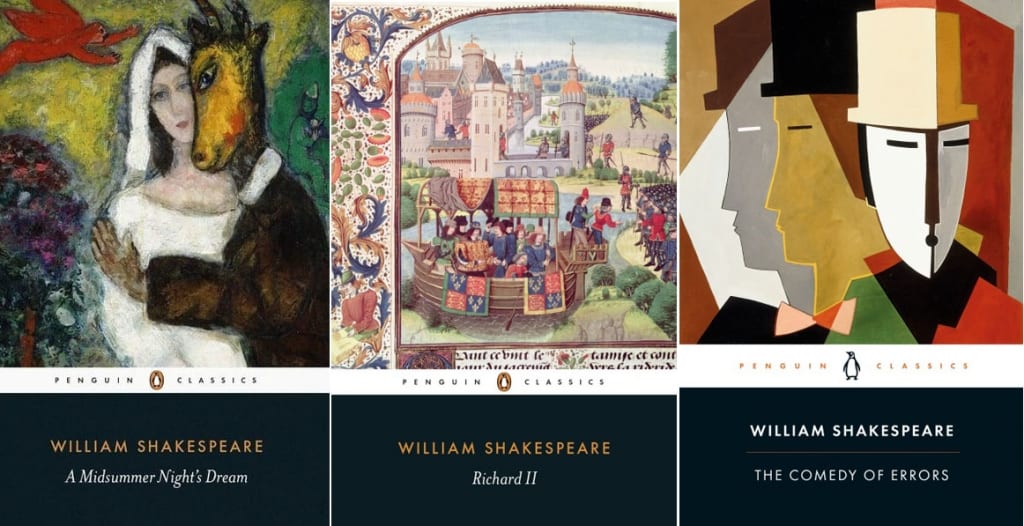

After I completed my degree the Director of the Shakespeare Institute, Professor Terence Spencer, appointed me to a fellowship. When he became General Editor of the New Penguin Shakespeare edition, he appointed me as Assistant Editor. I helped to draw up the editorial principles, checked typescripts as they came in, and read proofs. I was also to edit three plays for the series: A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Comedy of Errors, and Richard II. It was invaluable experience. During these years I taught on undergraduate courses in Birmingham and Stratford and supervised graduate dissertations at both MA and PhD Level on a broad range of subjects.

How did you come to focus on editing Shakespeare’s plays?

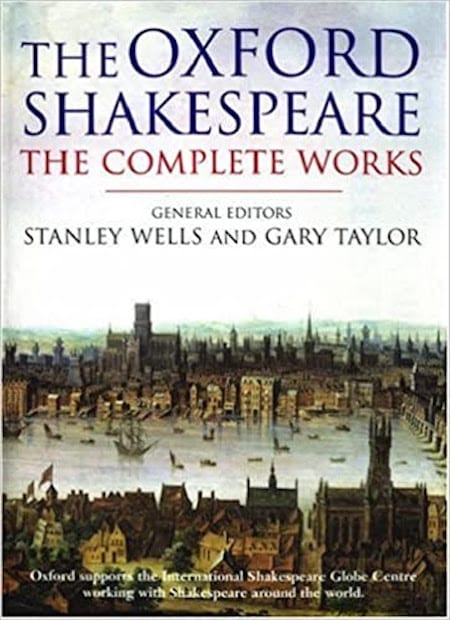

A major change in my career came around 1978 when Oxford University Press invited me to supervise the preparation of an edition of the Complete Works and to do it in-house as a full-time job. I wanted to think through the principles on which an edition should be prepared from the ground upwards. Almost all previous editors – all I think since the eighteenth century – had taken a pre-existing edition and revised it. I began by making a thorough study of the principles of modernising spelling and punctuation, which was published as a monograph. I determined that we would not mindlessly follow precedent but would make reasoned decisions about, for example, the order in which the plays should appear, the placing of the poems and sonnets, the prominence given to act and scene divisions, and so on. We and my colleagues would reconsider the relative importance of the early texts, Quarto and Folio, and rethink changes traditionally made to them.

Can there ever be a definitive edition of Shakespeare or a definitive production of a particular play?

There can of course, be no definite edition of Shakespeare. But is possible and proper for editors to question previous editors’ assumptions and to take account on new theories and of advances of scholarship. We were working at a time when what is known as the revision theory was coming into prominence. Putting it briefly this supposed that when a play exists in two early texts, one Quarto and the other Folio, they do not necessarily (as had previously been assumed) represent one inferior and one more ‘authentic’ text but may each have their own validity, representing the play at different stages in its evolution. The most conspicuous example is King Lear, and as a consequence, we printed two versions of the play, one based on the Quarto the other on the Folio.

Just as there is no definitive edition so, and to a far greater extent, there are no definitive performances. Indeed one might reasonably suggest that there is no such thing as a play – there are only a continuum of performances that take a printed text as their starting point. Each performance varies according to the gender, personality and physique of the actors, cuts and other changes to the text, the set and costumes, the music, and innumerable other factors.

How far have Shakespearean productions in any period relied on the tension between text and context?

From the Restoration onwards, texts were freely adapted, sometimes to make them more topically relevant, often to conform to current theatrical fashion and to showcase the skills of star actors. Just to give one example, Henry Irving sometimes ended The Merchant of Venice with Shylock’s exit.

A major change came with the Harley Granville-Barker (1877-1946) productions of Twelfth Night, The Winter’s Tale, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream at The Savoy Theatre in 1912-1914. Barker used almost complete texts. This practice had a major influence on subsequent productions including those of Peter Hall and John Barton and eventually in our own time on Gregory Doran. I greatly admire their work, and that of Peter Brook, for their probing rethinking of the original texts.

Are there particular features of productions in recent decades that you admire or dislike?

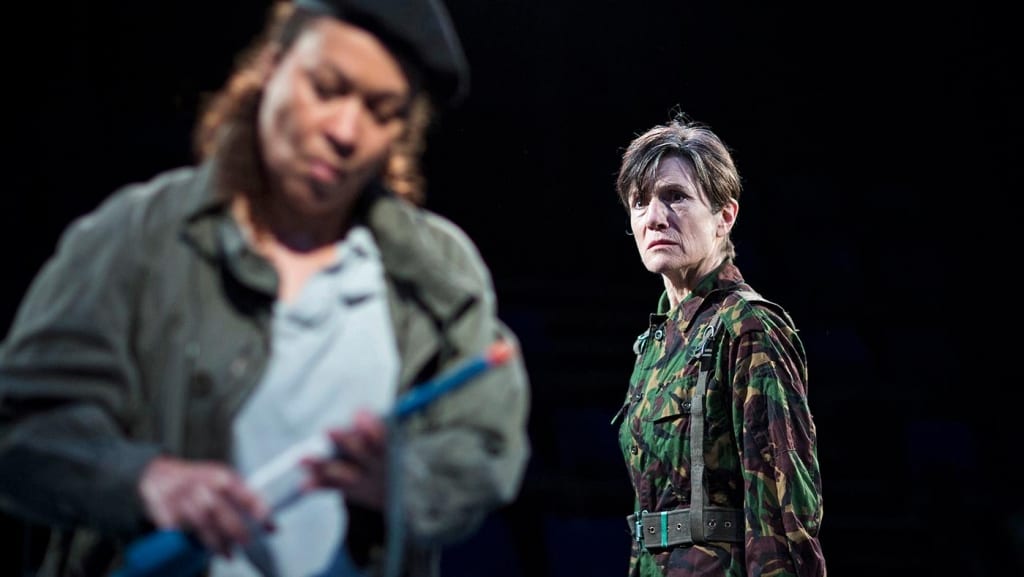

In recent years British directors have experimented with techniques such as gender-blind casting, colour-blind casting, use of physically disadvantaged actors, and so on. Such techniques are often successful and can be ingeniously deployed. For instance, Phyllida Lloyd’s all-female productions justified their originality by proposing that they were put on by the inmates of a woman’s prison. But often productions seem merely gimmicky. For me what matters is whether production techniques serve the play rather than seeming to put social issues above artistic ones. Putting it simply, some productions seem to use Shakespeare for social (and other) ends rather than being concerned to offer an interpretation of what Shakespeare wrote. Having said this, however, one must add that, genuinely creative adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays in many media – theatre, film, opera, television, prose narratives, and so on – may have independent artistic validity.

Why do you often refer to Shakespeare as a ‘romantic’?

I call Shakespeare ‘romantic’ because he doesn’t conform to neo-classical rules. He mixes comedy and tragedy.

Why did Shakespeare follow one play with another of a contrasting mood or mode? Was this sequencing driven by Shakespeare’s own artistic priorities or by the practical needs of his Company?

I think he varied his dramatic modes partly because he wanted to offer audiences variety and partly because every play he embarked on was a new adventure, a response to new challenges and to shifting tastes in his audiences. So it’s a mixture of his own artistic priorities and the company’s needs.

You point out that the division of Shakespeare’s plays into scenes and acts was in many cases an editorial intervention and not part of his writing practice. Does this mean that many of his plays were performed straight through without intervals?

Yes, I think it’s very likely that his plays were originally performed continuously.

You have worked extensively on the Sonnets recently: how does the study of the Sonnets help us to understand the mind of Shakespeare the dramatist?

I see the Sonnets as largely private poems, not related to the plays.

You describe yourself on Twitter as in part a ‘controversialist’? What does this mean in your own case, and why does it help to be controversial?

I describe myself as a controversialist because I have not been shy of taking a stance on disputed issues, especially the challenges to Shakespeare’s authorship (see, for example, the free e-book www.shakespearebitesback.com ), though he certainly collaborated with other writers especially in the early years and towards the end of his career). The question of how much of his work is collaborative is a major topic of current scholarship.

You have been associated for many decades with Stratford’s approach to Shakespeare. Has Stratford been influenced by the performance practice of the Globe Theatre in the last few decades or vice versa? Can/should the two theatre companies collaborate more?

I don’t think there has been much interplay between Stratford and The Globe though both companies have responded in varying degrees to current trends, possibly – and only in the case of the RSC – influenced by the Arts Council’s funding criteria.

With the theatre closed for COVID-19, just as it closed at intervals for the plague in Shakespeare’ day, how can his work help us through this time?

Even now that theatres are closed there is ample opportunity for people to engage with Shakespeare through online performances and through television and film.

Is Shakespeare more of a cultural icon now than at the beginning of your career or has this been a natural progression?

Film and television have helped to spread Shakespeare’s influence worldwide.

We would love to know what sort of man you thought he was.

For my views on what sort of man Shakespeare was you need to listen to my recent lecture series: ‘What was Shakespeare Really Like?’ There are four of them and these are freely available at www.shakespeare.org.uk/wells-lectures

Modest, hard-working, highly intelligent, sexually ambivalent, deeply concerned with his personal relationships, loyal to his family: these are some of the characteristics that come to mind.

Lastly, on your 90th birthday, we were wondering how you would like to celebrate in the style of Shakespeare?

I’d like to take Shakespeare himself, and his patron, The Earl of Southampton, to one of my favourite restaurants, The Ivy, on West Street, in the heart of London’s West End. I would recommend that they have the Roast Devonshire Chicken (for two), followed by the Baked Alaska.

Many thanks for addressing our questions, Professor Wells, and we congratulate you on your birthday. Clearly, you are not planning on slowing down any time soon.

- Thanks to all contributors: Tim Hochstrasser, Grace Barber and Rivka Jacobson.