In the digital age, when old school printed newspapers fight for survival, and yellow press journalism has modernized into a soapbox to air celebrities’ dirty laundry and alarmist anti-immigration headlines are a modus operandi, the Daily Clarion newspaper of Mark Jagasia’s play of the same title feels more real than fiction.

Premiering at Hackney’s Arcola Theatre, Clarion is set in the space of one apocalyptic day, darkened by doomsday horoscopes and an impending tempest of political scandal and police investigations. For all intents and purposes, the Daily Clarion is a fated ship, buffeted by the Homeric waves of retribution, captained by a “deeply weird, sexually malfunctioning headcase” of an editor and staffed by a pissed Fleet Street legend out for blood, sailing straight through the mists of mutiny and towards demise.

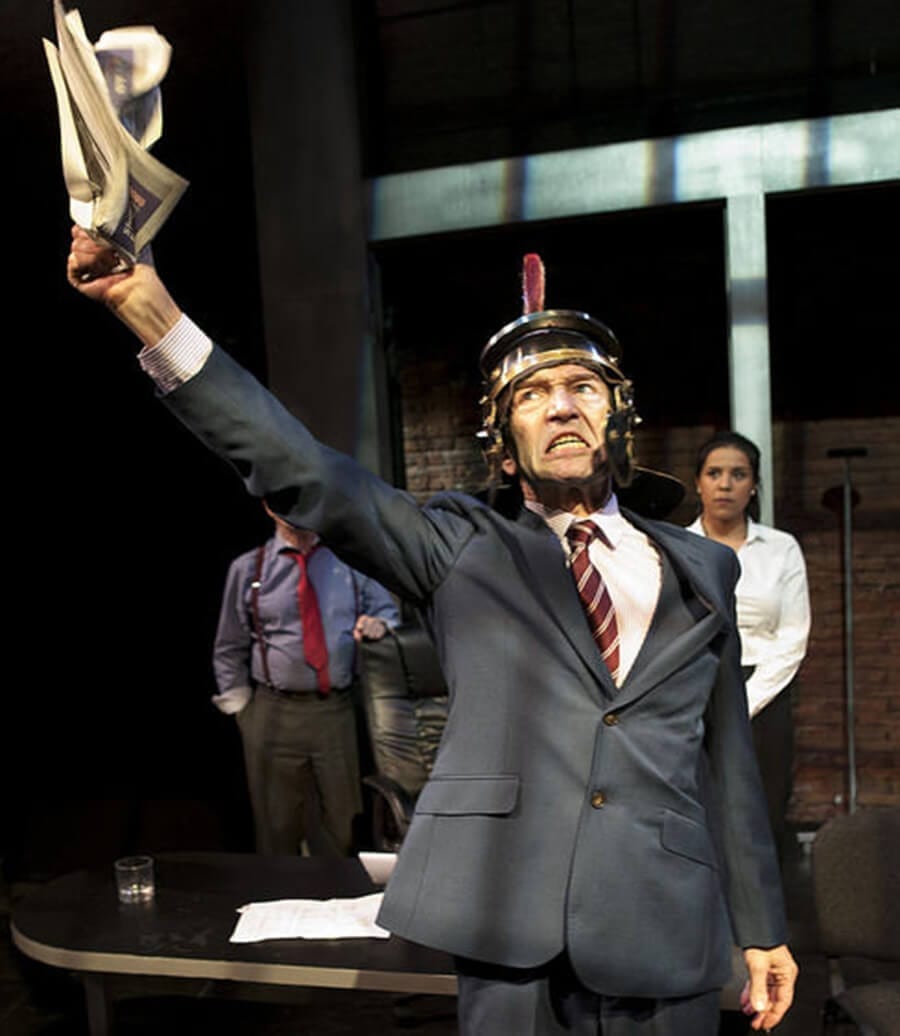

Clare Higgins delivers a remarkably tenacious performance as Verity Stokes, with uncanny air of Dame Judy Dench, and Greg Hicks as the Caesarian helmet-wielding Morris Honeyspoon channels the xenophobic spirit of a newspaper staffed with “the editorial authority of a drunk attempting to punch himself on the nose – and missing”. With such farcically Dickensian characters at the helm, Clarion is serenaded into inception by Greensleeves and induced into conflict with clattering thunder and howling winds, riding an undercurrent of urgency all the way through. The stage is refreshingly intimate for a newsroom setting, yet markedly sibylline. Underneath a beam with Daily Clarion emblazoned in foreboding red letters, and with a gradually darkening London skyline looming ominously, Clarion is a play of quick wit and rapid scene changes in the spirit of similar television programs, but with a moralistic cleaving edge.

The conspiratorial note crescendos in the second act of the play as it whirls into a maelstrom of accusations and vitriolic diatribes. We can only sit and wait for what seems to be the inevitable closing, the call to the bloodthirsty lawyer-hounds and political devouring of a newspaper dead-set against a more liberal world. And we could sit on the edge of our seats, laughing in between scenes changes lit in red like a sinking submarine. While the actors may stumble once or twice over their lines, and even though half the humor is media jargon, and the other half seems to be ripped out of an English Literature student’s notes on the Classic and Hellenistic periods, this play is critical for any member of any generation to see (but most especially if you happen to have studied three years of Anglo-Saxon poetry).