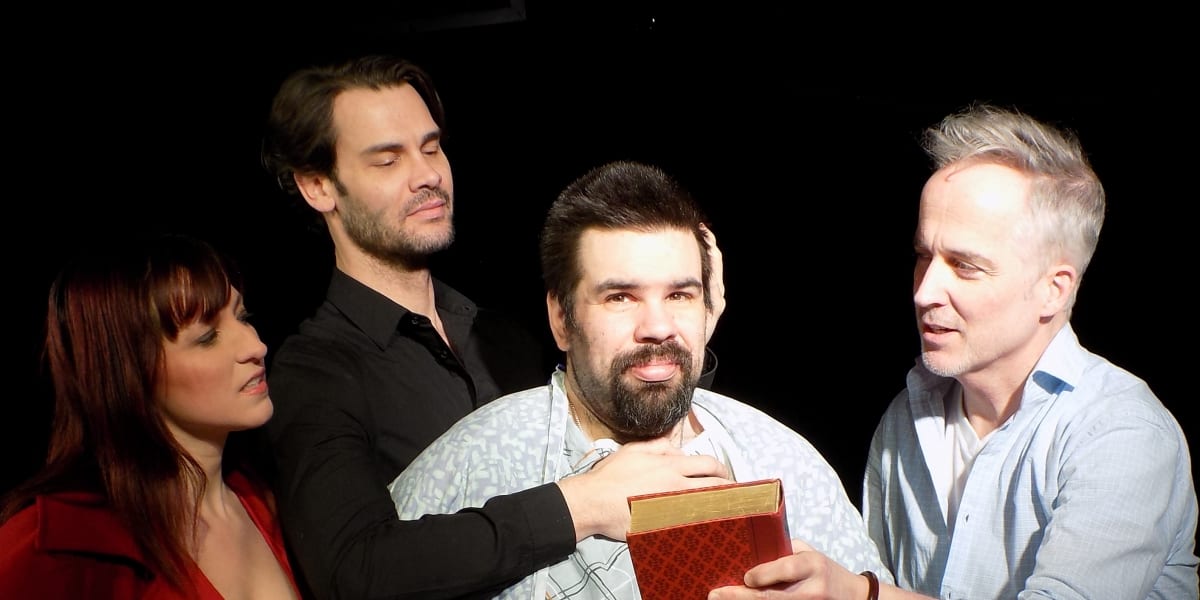

What is in an identity? Is it something inherent in us, a labeling system society imposes or that we impose on ourselves? How are identities formed and can or should they be taken away? These are some of the issues that Identity grapples within its rather personal depiction of a man’s life through his three identities: disabled, gay, and Catholic. Mike (writer Nicholas Linnehan) opens the show tied to a bed and in a hospital gown. He is confused and vitriolic against the mild-mannered and ultimately tight-lipped doctor (Matthew Tyler) who he first encounters. After their altercation, Mike pauses from the scene, slips out of his restraints and addresses the audience in an opening monologue. He puts forth that he writes when he is inspired, but also when he is feeling high emotions. What will subsequently follow is his life, or the life of someone called Mike at least, told in fragments and bursts and ultimately with a lot of asides and meta-references for the audience on how he dealt with three often opposing and socially oppressing identities from which he cannot figure out how to escape.

There is a lovely rhythm to the writing of the monologue and audience asides. Mike’s opening monologue continually repeats the phrase “I’m different”, a line both freeing and constraining in its acknowledgement. Likewise, Mike takes a moment later on in the act to read a poem from a black marbled notebook in which he addresses the frustration and loneliness that comes from not being disabled enough for some groups yet too disabled for others. The production value is on the lower end of the scale, with clearly plastic fruit or a robe that’s accidentally inside out. As the play goes on, this dissonance of community theater is less distracting, especially as the meta-referencing allows for the acknowledgment of the ‘wires’ theatre can sometimes have. However, the occasional stiff or overindulgent acting moment from the troupe or hokey premise can be a little off-putting to watch. In the end, however, most of these stumbling points fade away and the second act proves particularly strong.

The theatre as the personal can fall victim to self-indulgence, and even Identity falls into this trap. Yet, the personal truth which seems to be invoked here feels so real and the charm of our leading man so authentic, that those rare slips do not hurt the overall sweetness and appeal of the production. The play could use a fine trimmer to slim out some of the overworked scenes and dialogue, but much of the production and its mixing of genres and styles proves enjoyable and touching.