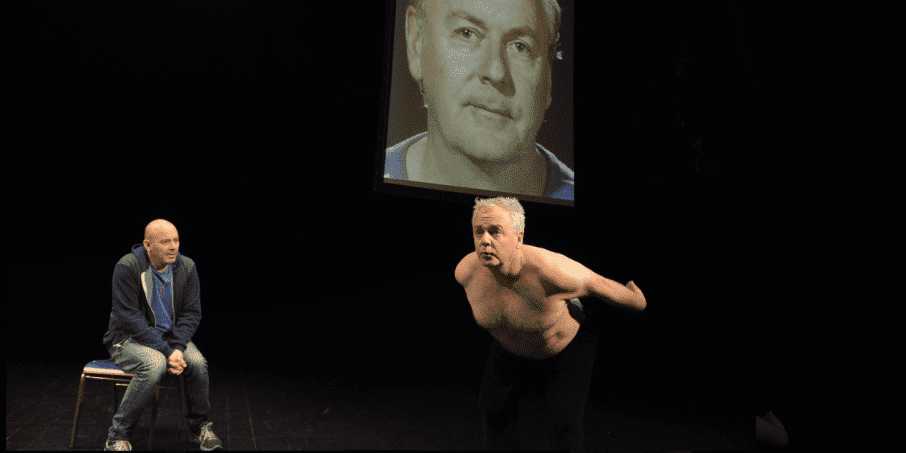

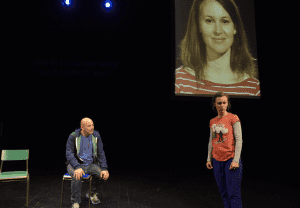

A man who takes himself for a bird, a woman obsessed with her sleep, another man who masturbates thinking about his friends… These are the endearing people you meet in this Australian play. This project originates from conversations that the director had with complete strangers he met in the streets of Melbourne. Adriano Cortese invited them to talk and have a drink at his apartment and, in a short time, fifteen people were there confiding very intimate things! How much can you open up to others? Why is it sometimes easier to confide in strangers? To answer those questions, Cortese proposes a very simple staging and scenography: at the centre of the stage, two bar stools; in the background, a big screen projecting the actors’ faces in close-up and, in the foreground, a guitar.

This results in a stirring show that celebrates the poetry of daily life and lets us hear the intimate words of such people with great sincerity. For instance, one of the most touching and amusing anecdotes is about the craziest things a man has done for love: he was sleeping with his girlfriend who suddenly woke up and declared she was extremely hungry so, naturally, he got up to make her some pancakes only to find her fast asleep upon his return. This episode is made comical by the girl’s confession that she ‘would never have done something like that’ for him – sweetly tragic, unrequited love.

Intimacy is incredibly authentic. Cortese introduces a form of ‘anti-acting’ – an idea that suggests a ‘character’ does not actually exist. And, indeed, this show does question and blur the lines between the character, the actor and the real individual. More than that, the actors really listen to each other, as if they are discovering the speech alongside the audience and then succeed in mapping it onto the present moment. Another very good point – relatively rare in theatre – is the use of a form of conversation that does not exclude gaps and pregnant pauses; there are some moments when the actors just look at us… not saying a single word.

Unfortunately, the background music detracts from these moments of carefully curated silence. In fact, the music disrupts the entire performance. This subtle and clever play suffers almost because of its tentative approach. The idea of ‘anti-acting’ remains understandable, but it would still be possible to remain sincere whilst portraying your character in a more powerful manner. It seems to me that the search for authenticity does not necessarily lead to an interpretation as naturalistic or cinematic as intended – it is a type of acting seen over and over in recent years.

However, the great performance of Patrick Moffatt is an exception to the rule – he convincingly portrays the man who believes himself to be a bird culminating in actually becoming the bird itself! His show within a show, at first, seems ridiculous but this eventually subsides into an appreciation of the poetry behind his animalistic interpretation.

As more than a homage to theatre, Intimacy remains a moving praise of our sensitivity and humanity in general, despite some unfortunate staging bias.