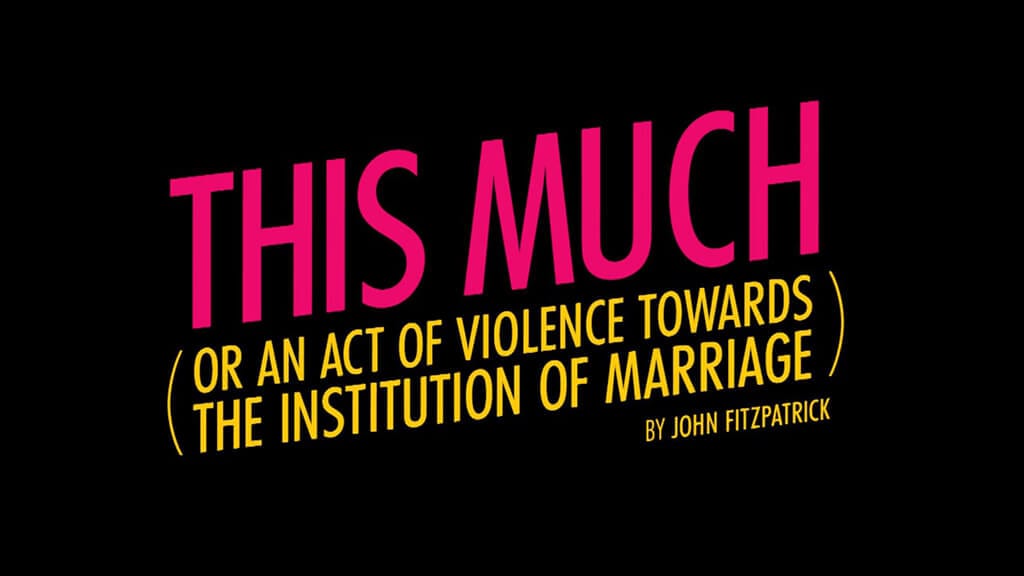

[dropcap size=big]K[/dropcap]ate Sagovsky is the Artistic Director of Moving Dust, an emerging multi-disciplinary performance company. John Fitzpatrick is a playwright and associate artist of the company, developing a controversial new play through the Royal Court’s writer’s programme, This Much (Or An Act Of Violence Towards The Institution of Marriage), which will premiere at this year’s Edinburgh Fringe. The show is also a dramaturgical collaboration between Fitzpatrick and Sagovsky, unearthing themes of identity and relationships in the light of the current changes in legislation and gay culture. We meet outside the Oval Theatre, where the show previewed and was followed by a fascinating Q&A.

KM: First thing’s first, how did you two meet and end up working together on this project?

JF: We were at Central (School of Speech and Drama) around the same time but I don’t think we actually met then.

KS: We were on different courses and it wasn’t until a couple of years after graduating, when I was directing a show with a big chorus, and John got roped in from the pool of Central actors that we met. We got on really well in that show and started making work together.

KM: So from training as an actor, John, you’ve moved more towards writing over the last couple of years.

JF: I couldn’t find the work that I enjoyed doing as an actor. Acting had fulfilled everything that it was going to for me, in terms of the work being offered. It seems that unless you’re really successful then you don’t have a lot of choice in what you do and I wasn’t very satisfied in just doing TV commercials. It wasn’t until we first started properly working together that I decided to pursue writing. I found the process more collaborative – something that you didn’t have to do alone in your room but you could work out the answers in a rehearsal room. It’s about not being authoritarian with the text and never pretending you have any answers. You’re just trying to hone in on an instinct. The actors and director use your script to find that instinct in themselves and hopefully we’re all tapping in to a greater instinct of something that needs to be talked about.

KS: In the broadest sense we’re two artists who enjoy making work in lots of different forms. For example, John is also a film maker and live artist and makes work with – what do you call it?

JF: Protonorm Tranarchist Pop group. We’re called Laura Ashley. We dress like middle class mums in the 90s and we rap.

KM: In This Much there’s a fluidity of boundaries between audience and actors, as well as how the set is deconstructed and remade. Was this fluidity something you found in the rehearsal process?

KS: One of the things I love about theatre is it’s where objects and physicality also become metaphorical. Written in to the script there’s frequent reference to objects and how these men are trying to build their lives around an image of the ideal. The fact that it’s a B&O speaker, the Kenwood Kettle, the Nutribullet, it’s deliberately specific. It’s Anthony’s flat but they all have a relationship to it and they all interact with the design elements, literally making their world. We wanted something reminiscent of high end fashion shops, where you’re not sure if it’s a clothing outlet, a gallery or a really posh flat, hence the rough chic Espy boxes with expensive lights and mirror tiles. Visually we wanted to show how they’re constantly trying to make and remake a world that can’t be controlled because the internal mess keeps becoming external. The tidal wave of crap then bleeds in to our world, which I like because the audience represent the people in their heads or online followers who they’re trying to impress. Part of the characters’ downfall is about the viewing eye, and what they want to be seen and not seen, as they literally frame parts of the stage action with the see through boxes. By the end all three characters are trapped in a sort of boxing ring and by the clutter of their own lives; that all developed in the process.

JF: It’s weird because advertising sells you belonging and the idea that we’re showing is that people try to fit in using objects. That became really clear to me in rehearsals. And I think in terms of fitting in, there’s so much complicated history in gay culture, particularly around self repression, that how gay culture sees itself now – well, that’s a whole other play.

KM: In the post-show Q&A you mentioned self loathing as a natural product of growing up always being told you’re wrong, which I thought was such a precise, psychological observation.

JF: Which is not just about sexuality, right? If you grow up as a woman, you’re always being told that you’re less. Of course there are things in society that are geared towards privileging certain people and not others, and it’s a tacit thing that you learn from an early age. I think you learn to hate yourself because the world is saying that what you feel on the inside is wrong. If that’s the case, you forge an external identity as a child that doesn’t correlate with who you really are. You feel like a fake all the time. Gar has to be pushed to the really desperate place before he realises that he has to break down that identity that was formed a long time ago.

KM: And Gar often isn’t very likeable…

JF: I think theatre should be like football, where you’re shouting at the player, “No! Do that! Don’t do that!”

KS: Gar does do really ridiculous things and sometimes you hate him and at the same time you understand him. He’s a classic tragi-comic hero. That’s what makes it so recognisable.

KM: You also talked about having to categorise This Much for Edinburgh programming and how coming under a LGBT label is both useful and frustrating.

KS: It’s massively complex. There’s definitely a tension between saying this is a show that has LGBT stories in it and that’s a selling point for a certain demographic, but at the same time the exact thing we’re trying to do is not flag that up because, actually, they’re just stories about people. And if we’ve succeeded, an audience couldn’t categorise the show.

JF: You need labels for visibility and they’re useful for letting people know that there’s something to stand up for and somewhere to belong. But really you should be able to belong anywhere. And it’s important not to capitalize on a label that’s for a section of society that’s been discriminated against, whilst using that specificity to sell it back to them. I think that’s wrong. It’s using capitalist techniques when theatre’s clearly not a capitalist art form, since there’s no money in it. You have to literally scrounge around for everything!

KM: Do you think the title of the play may cause offence in certain circles?

JF: I want to play to the worst expectations of someone who thinks this is the decline of society or the people who are saying gay marriage is causing flooding. I want to put my finger on it and say what exactly are you afraid of? Because if your institution is so great then it should be available to everyone. The new leader of the Woman’s Equality Party was asked recently whether equal pay for women would mean a decrease in men’s incomes and she replied brilliantly, saying, equality is like love; it’s not finite.

KS: We’re not setting out to cause offence, we want to create dialogue; no one has ever won anyone else over by calling them a bigot. Our hope is that anyone could come in and watch, and that the play would be provocative in the best sense. Having the conversation is what creates change. The subtitle isn’t An Act of Violence Towards Marriage, it’s Towards the Institution of Marriage. What we’re asking people to do is to violently question what they identify with. If a person responds with saying I really believe in the institution and this much of the ritual and tradition then that’s brilliant. We need ritual and tradition, theatre is embedded in it. Alongside it though we need strong questioning, especially where institutions become edifices annexed and peddled by people in power and we’re asked to accept or engage with these institutions unthinkingly.

KM: Kate, you also said that you felt that this was the year to do this particular production. Why now?

KS: I’m really excited by how online social platforms are giving previously invisible sectors of our communities more visibility – even 10 years ago that wasn’t there. It feels like queer culture is also currently apart of the emerging dialogues, of which there’s fascinating content to be found in popular online platforms. It seems that these discussions are influencing even legislation in terms of gay marriage. Where we are right now is a really complex place and it’s important that people can acknowledge that, as well as the pain, shame and repression. It’s a portrait of the mess we’re all in, not just the demographic who identify as gay, but the whole of society. In the show, Gar says “I want to be a new kind of man” but he doesn’t say what kind of man that is because he doesn’t know. But he does know that he wants to be seen and heard. So we’re not trying to say this is what the new masculinity looks like, but we are inviting anyone who doesn’t feel self actualised in their lives, for whatever reason, to acknowledge it and say can I change that and find a way to be me?

JF: I think the show avoids talking about right and wrong. Political correctness stops dialogue and the only thing that can work against structural inequality is dialogue, allowing people to talk. We’re at a point of great change politically, socially, economically and I consider the theatre a place where people can come and dream about their ideal society. I don’t know if this play is that grand, but we definitely want to be a part of the conversation.

This Much (Or An Act Of Violence Towards The Institution of Marriage)

Zoo venues (124)

Aug 13-15, 17-23, 25-31 ¦ 19.45