This year, at the Avignon ‘Off’ festival, Jacques Osinski’s take on La Dernière Bande provokes a particular excitement. When I enter the Théâtre des Halles, a small crowd is already there. Most of us are glad to see a Beckett play, but let’s face it, most of us were even more excited to see Denis Lavant in a Beckett play. The French actor, easily identifiable, is known for his acrobatic performances and his ability to transform into anything, using his unique face, voice, and body.

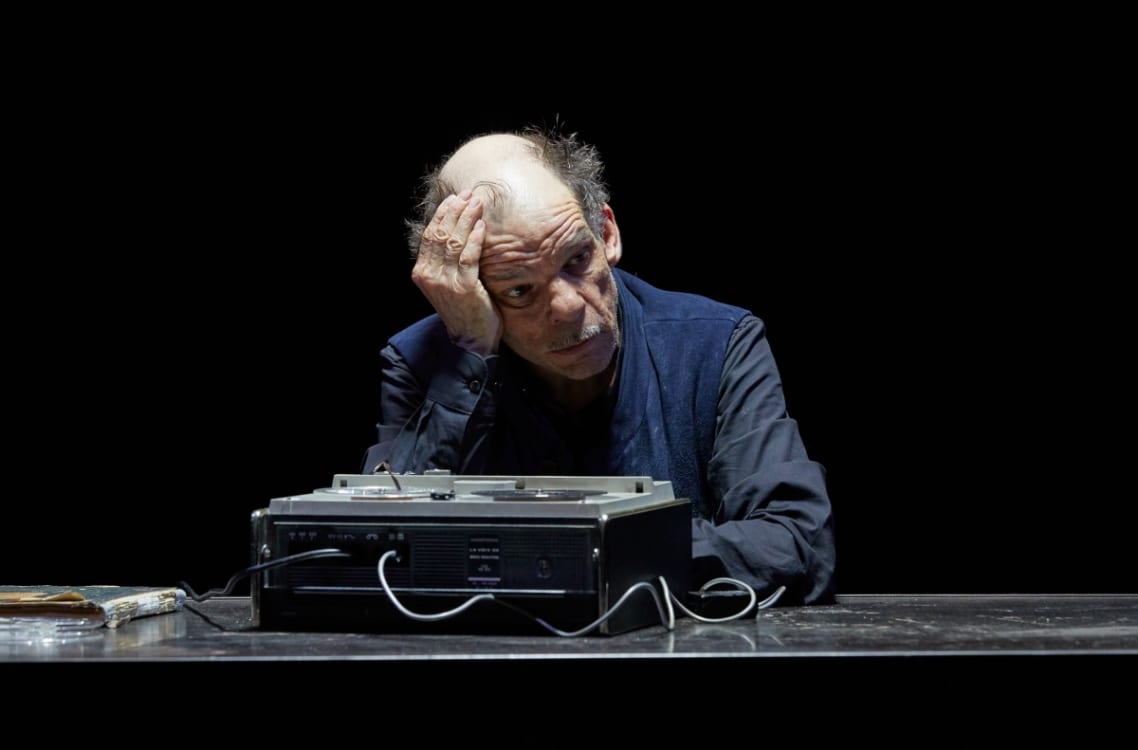

The first encounter with Lavant is breathtaking: the whole room is plunged into total darkness, but we can hear someone’s shoes squeaking, and then the creaking of a chair. Suddenly, a cold light turns on, brutally illuminating Denis Lavant from above. He is sitting at a desk, completely still, and during never-ending seconds, and maybe a couple of minutes, he does not even blink his eyes. The tension grows (how much longer can he stay like this?) and my eyes, captivated only by Lavant’s presence, barely see what is around him. A tape recorder is in front of him, along with several cardboard boxes stacked on his desk.

Against all expectations, Lavant takes a deep breath, and he’s off. He starts moving, and everything he does is extremely precise. He gets up, opens a drawer, forms a 90° angle with his body in order to see what is in the drawer, and takes a banana. With burlesque mimics, Lavant carefully peels the banana. The fruit’s skin falls on the floor, and in what could be a scene from a Chaplin, Keaton, or Tati film, Lavant slips on the coloured obstacle and grunts. When he gets another banana out of the drawer, the audience bursts out with laughter: it is as if what we have just seen was a film that was rewinding and starting over.

This pattern of the rewind movement is central in Beckett’s play, in which the only character, Krapp, listens to tapes of him talking that he recorded many years before. When listening to the tapes, he skips some parts of what he hears, laughing at his 30-years-younger self: ‘hard to believe I was ever as bad as that.’ Lavant’s acting brings a touch of humour to the situation, but his husky and veiled voice betray Krapp’s melancholy.

The lighting, which is very simple and stays exactly the same throughout the play, is sober but clever. It isolates the desk from the surrounding total darkness, and highlights every detail, whether it is the wrinkles on Lavant’s face or the dust escaping from the pages of his dictionary. It also reinforces the impression of Krapp’s solitude, even though the darkness seems to comfort him: ‘With all this darkness around me I feel less alone’.

Krapp searches for memories of what are probably lost loves, listen to some sentences over and over again without seeming to be satisfied by them. The only thing that delights him is to pronounce the word ‘bobine’(spool), which he is fond of. He could be an old man losing his mind or a child learning to pronounce new words and learning how to read: this is Denis Lavant’s magic, and he makes a very touching Krapp that will surely be remembered.

Summary in French:

Si les spectateurs du Théâtre des Halles viennent voir La dernière bande de Samuel Beckett, une bonne partie d’entre eux vient particulièrement pour le comédien qui l’interprète dans cette mise en scène de Jacques Osinski : l’unique Denis Lavant. Sa performance ne déçoit pas: entre comédie burlesque purement corporelle et accents plus mélancoliques, la présence incroyable du comédien maintient une tension de la première à la dernière minute de la pièce.