New director Chryssa Georganta, with the theatre group CONXOBANX, presented her own staging of Euripides’ Medea for two consecutive nights at the Michael Cacoyannis Foundation theatre. This is a low cost production, comparable though in intensity, inspiration and professionalism with expensive stagings produced by mainstream theatres – proving thus that you can create a high quality theatrical experience with meagre materials.

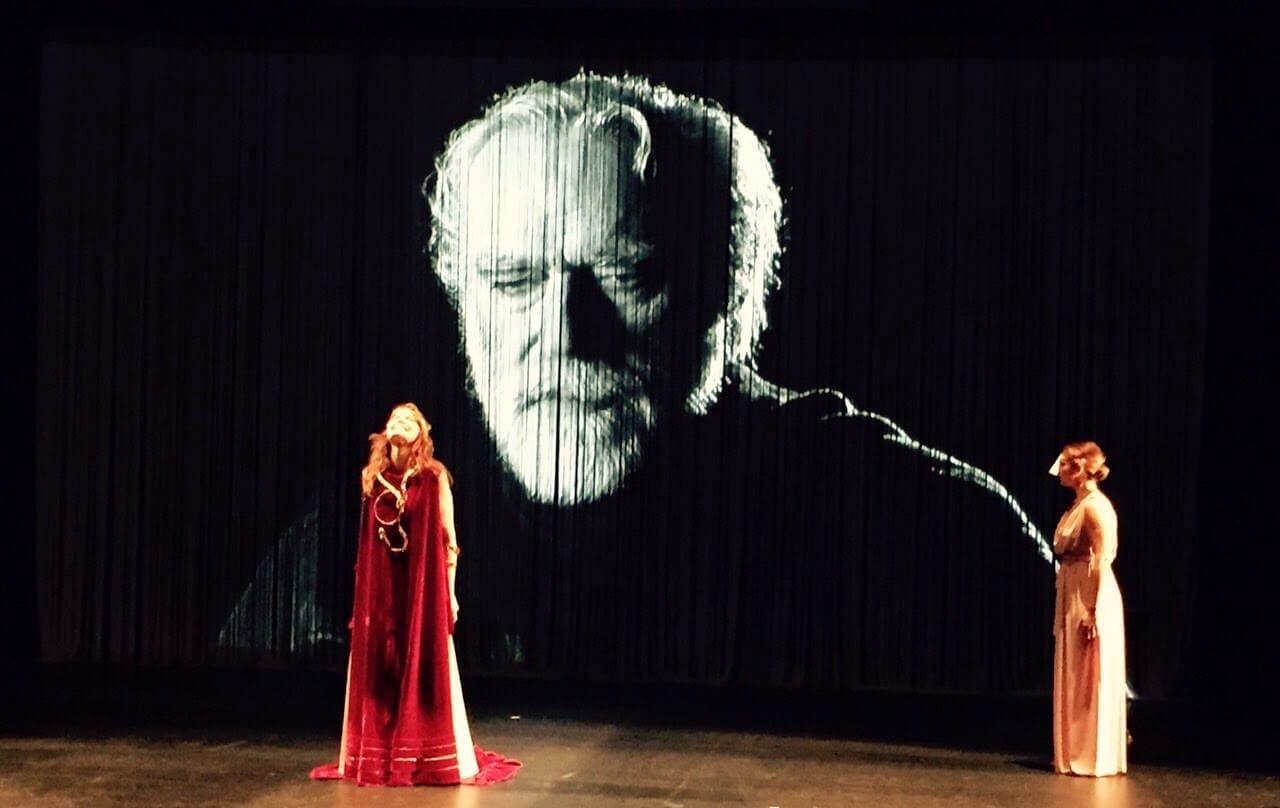

Georganta creates a visually strong and memorable rendering of the Euripidean tragedy. Her show features discreet live and recorded music, as well as projection of images and videos at the back of the stage. With the effective use of multimedia, the show works with only two actresses on stage: one of the two female members of the Chorus and Medea herself.

Medea is the only one among the characters that physically appears on stage; all the other characters interact with her projected at the back of the stage. What also sets Georganta’s Medea apart from all the other characters is her language; Spaniard Marisa Lull is the only one among a Greek-speaking cast to speak Spanish only (the show features surtitles in Greek, as she speaks). Medea is thus established from the start as the foreigner, the stranger, the (threatening) other. Georganta in her theatre note gives the play political dimensions (associating it to times of crisis that bring to the surface symptoms such as marginalization, bullying, violence and xenophobia); such dimensions, though, are not discernible in her staging.

Medea and the Chorus member move on an almost bare stage – save from a loom on the left, in which the former will weave the garments that will offer as a lethal gift to the newly wed bride and her father, Creon. This loom is lit even before Medea appears onstage and it is properly lit at crucial moments in the play, becoming a protagonist as much as Medea is; even when Medea lies to Creon, the loom is fully lit, exposing her plot.

Medea is at once a dignified Queen and a lustful, deceitful woman, as her carefully designed dress also indicates: on top of a white satin garment, looking like a nightgown, she wears a deep red, luxurious velvet dress and a golden necklace, shaped like a snake. After committing her dreadful deeds, she removes whatever is royal about her appearance; in her nightgown, she listens titillated to the voice of a servant narrating offstage the painful death that father and daughter met. In what becomes a highlight scene of the play, Medea dances a sensual, erotic dance – finely choreographed by Lull herself – reminding of a sexual intercourse. The final scene, where love and death are intertwined, is visually strong and striking: in the ‘bed’ where Medea lays, as her erotic passion has culminated, she moves her hands between her still wide open legs, only to bring out – shouting in pain, as if delivering – two umbilical cords. This is what Medea is left with at the end of the play; the haunting memory of love, the pains of labour and two lifeless umbilical cords full of blood in her hands.

Spanish actress Marissa Lull is captivating in her successive transformations from a tender, vulnerable, desperate to be loved woman to a merciless, cunning avenger; from a dignified Queen to a lustful woman; from a loving mother to a cold blooded offspring murderer. She uniquely portrays the extremity, the violence and the dark matter of Medea’s soul; definitely one of the best Medeas I have seen in recent years.

Georganta’s staging is, overall, a show cleverly directed and finely performed; a fresh, contemporary reading of a centuries old play without, however, flashy innovations empty of meaning that usually obscure classic plays, rather than shed a new light on them.