The lights come up on a man sitting in prison, writing his memoirs in the face of likely impending death. No, I don’t mean Monty Navarro from Gentleman’s Guide (though, come to think of it, the plot parallel is striking: a man dabbles in crime with questionable but non-malicious intentions and seeks solace in love with more than one woman…that’s a gross oversimplification, but I digress). This jailbird is Howard W. Campbell, Jr., the protagonist of Brian Katz’s Mother Night, his adaptation of the Kurt Vonnegut novel by the same name.

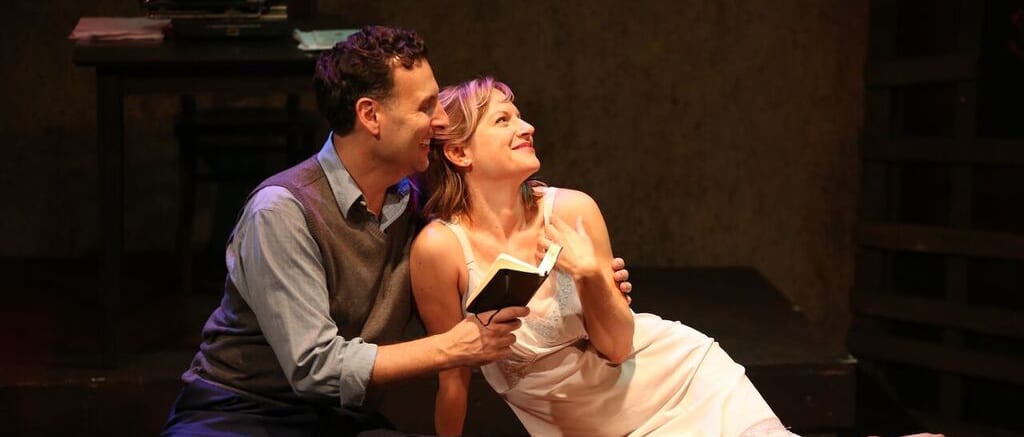

Mother Night is the memoir of Campbell (Gabriel Grilli), a fictional playwright and Allied spy. He recounts his life in vignettes of his encounters with high-ranking Nazis, Soviet agents, and everyone in between, portrayed by six ensemble actors each in multiple roles, in the heat and aftermath of WWII. As a broadcaster for the Nazis, Campbell secretly passed along coded information for the Allied forces after being recruited as a spy by an officer from the American war department. The show details his subsequent struggle with losing and re-finding his love, figuring out what to live for, and exploring the fine line between the propagandist he pretends to be and the antihero he actually may be. Katz preserves the meta-fictional style of Vonnegut’s original work, in that Campbell narrates large portions of the story to the audience. The show is thus made to feel almost like a reading of a novel in the first person. The play wasn’t all tell and no show, but I did find it to be a little too much narration – I might as well just read the novel. But such the style dictates. It did, at least, help set me back on track when the plot got convoluted.

One constant throughout the play is a fixation on the bleak, sweet release of death. Morbid? Yes. Relevant? Also yes. The story epitomizes classic nihilistic Gen-Z humor fifty years ahead of its time. Living is satirized as more contentious than dying. Doing right is more radical than doing wrong. And care is taken to connect the tensions of wartime society with the modern world; one character’s description of the WWII era as “a period of insanity that should be forgotten” may be meant to evoke some people’s views on the current political sphere. And then there’s Campbell’s standout line: “I doubt there has ever been a society that has been without young people eager to experiment with homicide, provided no very awful penalties are attached to it.”

That is one of the play’s strengths; its darkness unexpectedly bridges the generation gap for the two and a half hours you’re in the theater. Older generations can appreciate the play for reviving a story written earlier in their lives, and younger generations can laugh (if still a little nervously) with the characters who joke about meaninglessness almost as much as we do.

Andrea Gallo, as the officer who recruited Campbell as a spy, stole the show with her wit and intrigue. Her character, originally named Frank Wirtanen in the novel, is reimagined as Francis Wirtanen, the “Blue Fairy Godmother.” She exudes “girl power” in true dark Vonnegut fashion – she is the instrument behind his character’s historical fame and thus the instrument behind his subsequent downward spiral. And she’s not alone – in one exchange with Campbell, she mentions that the people who fed him the coded information he broadcast were all women who died for the cause. Now that’s a play I’d like to see next.