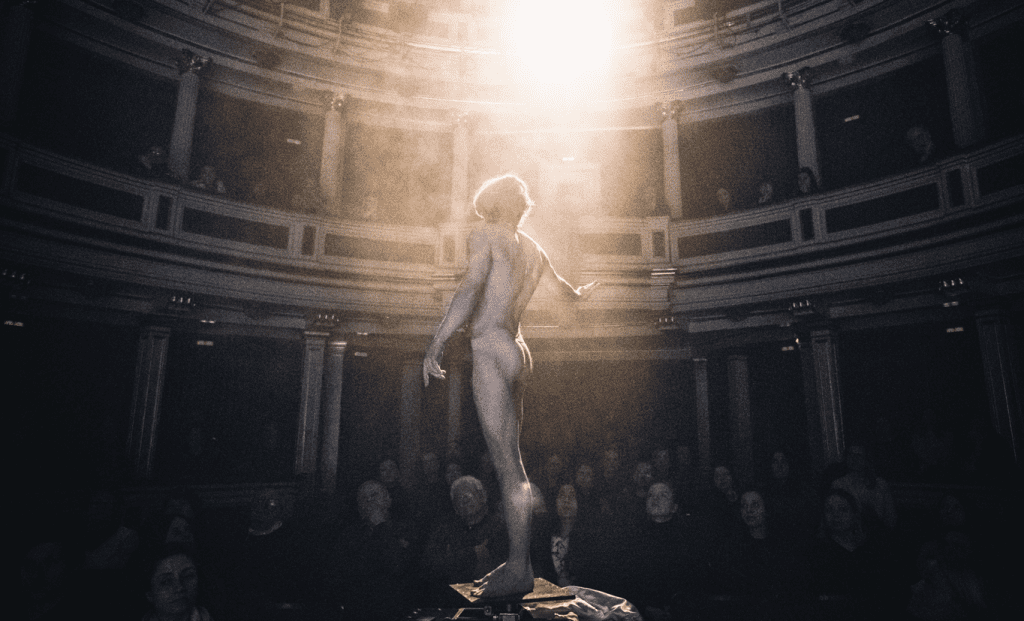

When the doors to the auditorium open to let the audience in, the performance seems to have already begun. On a rotating platform, in the centre of every spectator’s attention, spins a statuesque man covered only in glitter and dust. From the balcony one can hear a woman angrily and plaintively cursing “Odysseus, you a**hole, you broke my heart”. Between the seats flits a man who with a charming smile asks the incoming spectators for help in acting out the first scene of the play. Isn’t it a complete mess, you might ask? The answer is yes. But what a beautiful mess it is indeed.

Marcin Cecko’s drama is a loose adaptation of the Greek myth which intertwines the story of the legendary king of Ithaca with the history of Poland that has just gone through the democratic transition of 1989. Thus, Odysseus becomes a prodigal son who, upon returning home after years of labour migration, needs to reclaim the respect of his father and son, as well as the love of his wife, who’s been adored by nagging tradesmen for a long time.

Nonetheless, to recount the plot of the play would be nearly impossible because the boundaries between the scenes blur, making the performance resemble more of an oneiric journey through associations than a coherent retelling of the Odyssey. This seeming chaos, however, does not diminish the value of “Odys” in the slightest as one can get easily seduced by the strange beauty of the staging produced by, among other factors, the set design. The mythical Ithaca has no stable form since the rocks, corridors, and giant human limbs of which it is composed undergo an irreversible change with every alternation of the light. At times, it even becomes a living entity with its inhabitants softly melted into its form.

The play’s fluidity manifests itself in innumerable interactions with the audience as well. While the tendency to break the distance between the stage and the auditorium has recently become immensely popular in the Polish theatre, its implementation still involves the actors taking risks and the spectators not necessarily being on the same wavelength. Fortunately, this does not seem to be the case here. While the performers engage the spectators by talking to them, hugging or even kissing them, they respect the boundaries set in the “Decalogue” developed together with the audience during the open rehearsals.

The quality of the acting itself also compensates for the dramaturgical flaws. The cast manages both the longish philosophical monologues and the silent sequences well. Also, while the prevalent nudity could easily dominate the staging, the cast’s charisma allows for full control of the spectators’ attention. As a result, even long after the performance’s end, one still returns to the songs sung by Telemachus (Grzegorz Dowgiałło) or the quivery yet tender final encounter of Penelope (Joanna Drozda) and Odysseus (Paweł Siwiak).

This Polish Odyssey, written by Marcin Cecko, is by no means easy to comprehend. At times it is disorderly and confusing. However, the theatrical form that Ewelina Marciniak grants it enriches the story of this contemporary Odysseus with dreaminess and strangeness. Ultimately that makes the performance intriguing and absorbing.