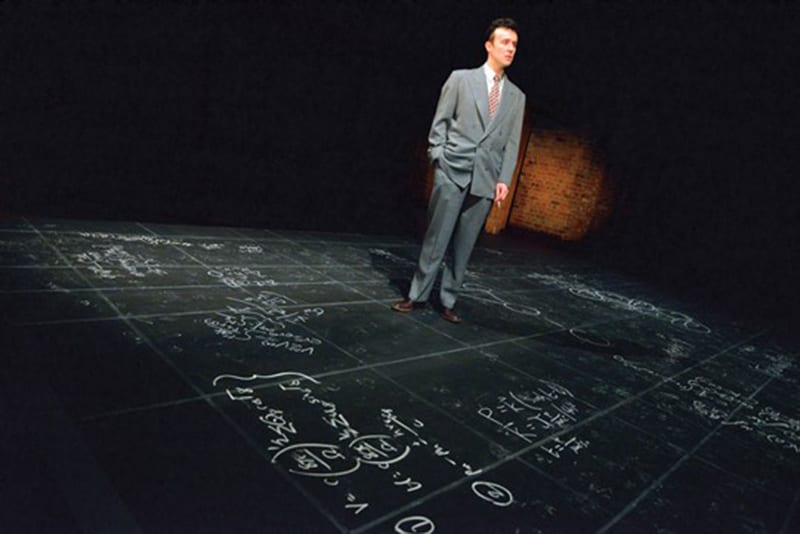

You will come to know me as Oppy, grins the gangly man in an ill-fitting suit as he scrawls his name, and the title of Tom Morton-Smith’s astounding new play, Oppenheimer, onto a blackboard. J. Robert ‘Oppy’ Oppenheimer has an enthusiasm for science that’s infectious. He loves science and dabbles in the arts, beguiling his audiences onstage and off with his particle physics, passages from Hindu teachings and his faintly arrogant charm. He’s a Cocktail Communist rather than a Champagne Socialist, sipping martinis and singing the Internationale at Berkeley Physics Department parties. This likeable man is also the father of the atomic bomb: the thin man behind the Fat Man that fell on Nagasaki and ended the Second World War.

Oppenheimer is a tragedy of epic proportions, tracing the bell-curve of the scientist’s life from the early wide-eyed days of theories, experiments and clouds of chalk dust to the aftermath of the atomic bomb when the chalk has been washed away by blood and he is plagued by guilt. “I feel,” Oppenheimer confesses, eyes now wide with horror, “like I have left a loaded gun in a playground.”

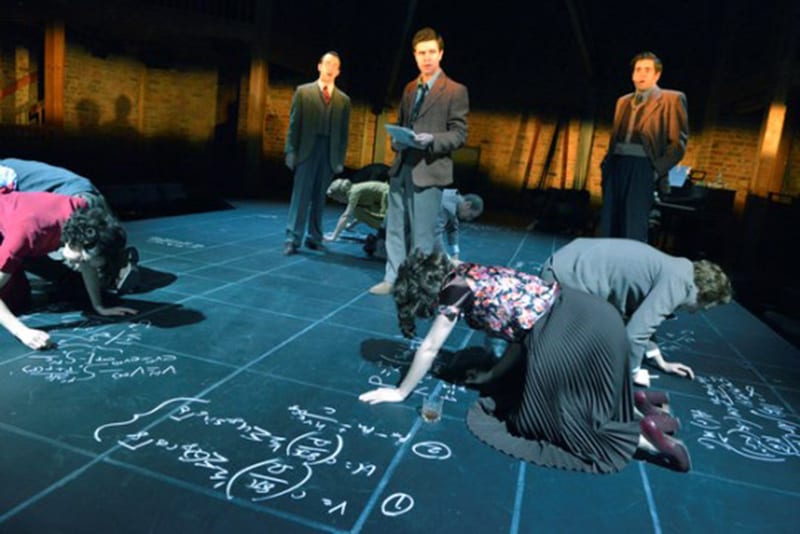

As ‘Oppy’ and his team cover the clever chalk board set with their equations they drift further away from the parties and the people to get deeper into the atom. The real Oppenheimer apparently once said “I need physics more than friends” and while Morton-Smith’s fictional version of the scientist is a little more social he still cuts ties with his Communist associations – a dehumanised collective term for his former colleagues, lover and brother – without blinking once the Manhattan Project begins at a top secret military base in New Mexico. Inside this bubble Oppenheimer’s race to finish the bomb before the war ends becomes alarming. It would be a shame, wouldn’t it, not to get to test it out? We agree. We can see how much passion and hard work has gone into the project. We watch spectacular test site detonation in awe. The fact that the next ‘test’ will vaporise people until nothing remains but shadows scorched into Japanese ground creeps up on us gradually and horribly.

Oppenheimer begins slowly but Morton-Smith is building an experiment and needs to do it carefully. He sets up a complex set of characters, colleagues lovers and friends, all excellently realised. Jamie Wilkes is particularly brilliant in his final scenes as mathematician Bob Serber, and also does a great Einstein impression. Thomasin Rand as Oppy’s fragile wife Kitty and Catherine Steadman as his passionate, mentally ill, fist-saluting Communist lover Jean Tatlock keep the science grounded in the terrible humanity Oppenheimer seems so desperate to escape. Examining his tragic hero with precision and clarity, Morton-Smith gets deep under his skin and splits him like the atom, releasing a volatile cocktail of genius, ambition, love and fear. John Heffernan is simply mesmerising in the role.

The legacy of then atom bomb is left to the last few moments of the play and it is devastating. There’s a strong sense of ‘Macbeth’ lingering around Oppenheimer. Maybe it’s the deed that cannot be undone or the fate of Jean Tatlock. Perhaps it’s the three hour running time or Oppenheimer himself, first strutting then fretting his hour upon the stage. Whatever it is, this ambitious play and its timeless concern for the sprawling humanity beyond the miniscule molecule may well become a classic. For now, Oppenheimer is essential viewing: physics has never been this powerful or painful, or produced quite so many goosebumps.