Iqbal Khan’s production of Othello has a deep split running through its middle. The first half is expansive and fast moving with the set changing fluidly as we move from the canals of Venice, to the opulence of a gilded palace, the open plains of Cyprus, a night club, army barracks, before finally settling upon the desolate beauty of a ruined church. It is this location which sees the climax of the first half: Iago and Othello pledging loyalty, after a piece of ritualistic violence, amidst the chaotic and syncopated rhythms of a beating drum.

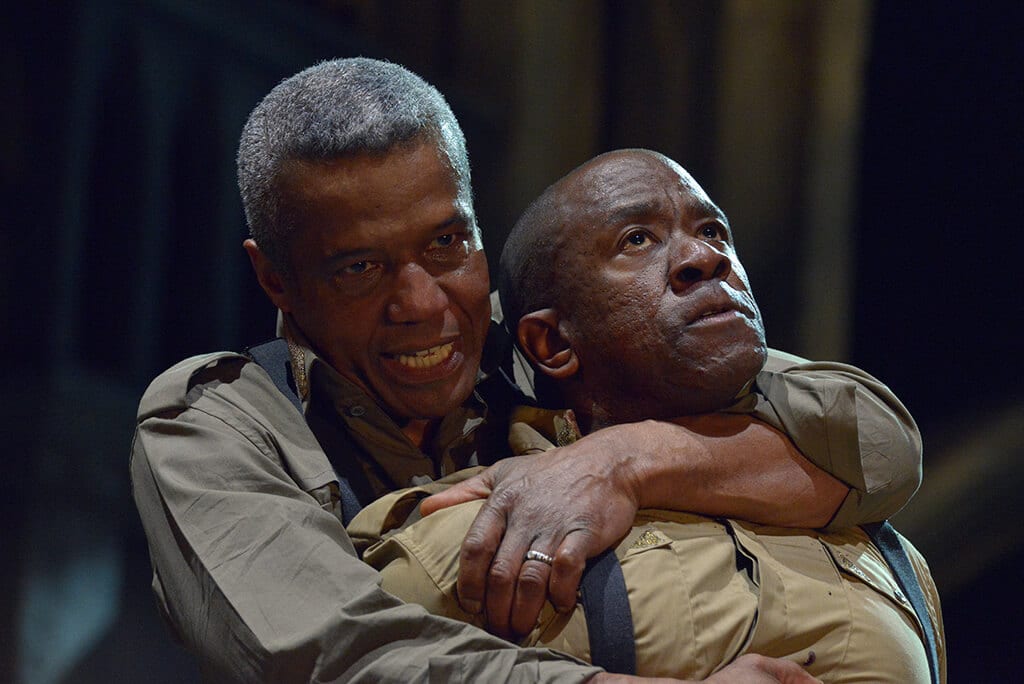

The second half, by contrast, is claustrophobic, briskly unwinding with a tragic inexorability, scenes take place mostly at night under the light of candles or hanging lanterns. The location is fixed: we are in Cyprus, most indoors. Whereas Iqbal’s first half exposed broad political, martial and geographic interests, his second half gradually strips away these accoutrements and lays bare something intensely personal: Othello’s transformation into a man capable of murder.

Foreknowledge of the play’s tragic outcome has a curious effect on the viewing experience, we watch Cassio’s interactions with Iago, Desdemona and Othello, with a sense of how they will later be interpreted and re-interpreted. In many ways, Othello is a play about watching and Lucian Msamati’s mesmeric Iago embodies this notion, his eyes constantly dart around the stage assessing his companions and their reactions; flickering micro-expressions continually reflect his internal, schismatic conflict.

Msamati’s Iago transcends his character’s Machiavellian origins and deepens them into habits which hint at a profound and unspeakable disgust with humanity— particularly, when this humanity is expressed in affection or physical contact.

There is one extraordinary moment early in the play (before Iago has attempted to contrive Cassio’s downfall) when, in a night-club setting, Iago begins singing in mournful plainchant. The sound is one of despair. His fellow on-stage revellers are stunned into a reverential silence. Cassio, to one side, sniggers drunkenly and interrupts him to begin a crude song of his own.

Iago as a black man surrounded by mostly black soldiers and Cassio cast in role of a white, upper-class, public-school officer, invests this scene with powerful new class and racial implications. Later, we witness an audacious but plausible rap battle between Cassio and a fellow soldier which culminates in a drunken explosion from Cassio, who believes he has been racially slighted. It is a powerful and interesting addition to the play’s dynamics.

In fact, casting Iago as a black man reconfigures many of the play’s internal tensions in interesting new ways. It suggests, for example, a possible camaraderie between him and Othello which might account for their subsequent alliance— although, it never simplifies this relationship to a simplistic tribalism. It also proffers a plausible new context for Iago’s dislike of Cassio from the start.

Hugh Quarshie’s Othello is played with an open cordiality. Interestingly, however, the production suggests an undercurrent of violence, showing him casually participate in the torture of another soldier. By introducing this possibility of violence, it helps to contextualise and foreshadow his transformation from geniality to green-eyed monster. Whilst Quarshie’s statesman-like authority is contrasted effectively with these bouts of psychopathic rage, his portrayal did not quite have the emotional clarity to suggest the different shades of his despair. Ayesha Dharker’s cameo as Emilia, however, amply provided some of the finale’s emotive power.

Otherwise, there were one or two moments of stylistic incongruity. On the whole, however, this Othello was aesthetically coherent, and combined original and nuanced performances with powerfully dramatic set pieces.