Writhing in the dirt and the rubble, half-naked in the flickering lights, the opening of Harry Melling’s peddling is abrupt and immediately hypnotic. The audience sits captive, as the pedlar boy (Melling) ferociously dances underneath the burning street lamps in a hazy Promethean state. Then, he awakens, eyes fresh and glazed over like an urban youth crawling out of London’s nebulous womb, unclaimed and unnamed, and he spurs into verbal and physical action.

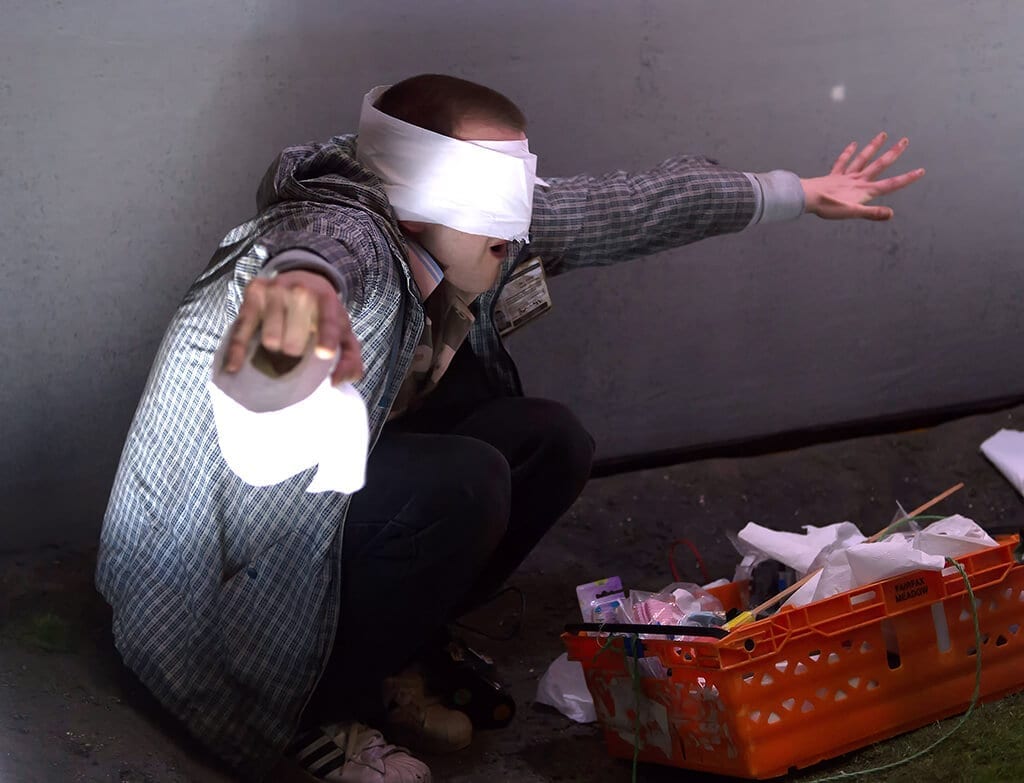

In making use of all four corners of his stage, Melling’s one-man show unravels at a relentless pace. His booming voice and raw poetry commands attention as he goes from door to door with his orange crate, selling “some might call it – life’s essentials”. At times, he foams with words, pressing his face against the mesh wall encasing his the stage, or pacing around the central pole like a rabid zoo animal tormented by the walls of its enclosure. At other times, the different bulbs flashing on set will seem to calm him, soothing his voice into dulcet tones.

The amount of activity and the range of emotion Melling achieves push his character to schizophrenic frenzies, yet we cannot look away. This pedlar boy, raging for recognition and burning for baptismal renewal is too familiar for us to ignore. We recognize his clothes, we recognize his voice, we recognize his orange crate of wares: and now, we can’t close our doors and escape him.

As representative of London’s forgotten youth, the pedlar boy’s search for recognition and identity leads him to somewhat Shakespearean questions of existence. And yet, for as unreal as a life of peddling may seem to the audience, the absence of an interval allows us to be immerse ourselves: we are chained to the pedlar’s reality. We struggle with him as he attempts to sell his wares only to get a fiver for his pains, as he threatens the gatekeeper little girl when her mother does not remember him even though his entirety of being is locked away in a file-box in her attic, as he tries to cleanse himself by throwing himself into water, yet clings to the pole for safety because he does not know how to swim.

Unassuming in its length, peddling is a must-see for the short time that it is in London. The emotion of the script and performance, and the manipulation of the set design, set this play apart as a modern piece dedicated to those forgotten masses swirling in the underbelly of London, those individuals living in the “cupboards” of society on knocking on the door of a vacant home, bought with foreign money. It is the gritty Odyssey of the modern world, a darkly poetic plea and self-contained paroxysm of a centripetal insanity, asking us to open the door rather than shut it, and consider his humanity.