Les ballets C de la B has an eclectic, holistic approach to its creations which makes both it and them hard to classify. Renowned for their collaborative ventures which break down conventional boundaries between performers and genres, their best work emerges from movement and musical forms that can embrace both joy and suffering in parallel, often drawing on European and non-European traditional expressions of each.

All these qualities are visible in this extended meditation on patterns and practices of mourning, but the whole is rather less successful than its individual parts.

As backdrop throughout runs a film of a woman dying for real: she is the dedicatee of the work – L or ‘elle’. This will doubtless prove the most controversial aspect of the evening, but in some ways it is in fact the least important. There is no tasteless attempt to aestheticise death here, but it does not add much either, fading into the familiar as the manifold activities of the musicians, dancers and actors unfold in the foreground and focus attention elsewhere.

There are many positives: the quality of the singing is quite outstanding – both pure, powerful and precise – in ways that we do not hear often enough at London’s prestigious opera houses. A central trio of outstanding voices perform and elaborate much of the music of Mozart’s Requiem with real brio, plangency and panache. Composer Fabrizio Cassol has a preference for groups of three that seems more intellectual than musically driven, but in this case you do not particularly miss the bass line, when it is still there often enough in the instrumentation.

Woven in and around the Mozartian fragments is a mash-up of African, in fact mainly Congolese, elements: another trio of singers, who are also the main dancers, together with two guitarists, and three likembe or thumb piano players. Supporting the architecture of the sound is sonorous accordion playing that strengthens harmonies and sometimes approximates to human breathing; and there are also memorable euphonium solos that echo the brass-heavy tones of the original Mozart, and a dynamic drum and percussion section.

There is great virtuosity here on all sides, but questions remain as to how well it all falls together in both structure and mood. To start with the whole evening is self-indulgently long: Mozart’s original lasts only 50 minutes whereas this sequence runs without interval for twice that length. In some movements, such the spare and chromatic Lacrimosa and the contrapuntal Confutatis, the insertion of different textures of sound and elaborate cross-rhythms added exciting elements of meaning of real value and insight. However, in other sections there was simply so much going on simultaneously it was difficult to discern the overall shape and direction or even tone of the whole.

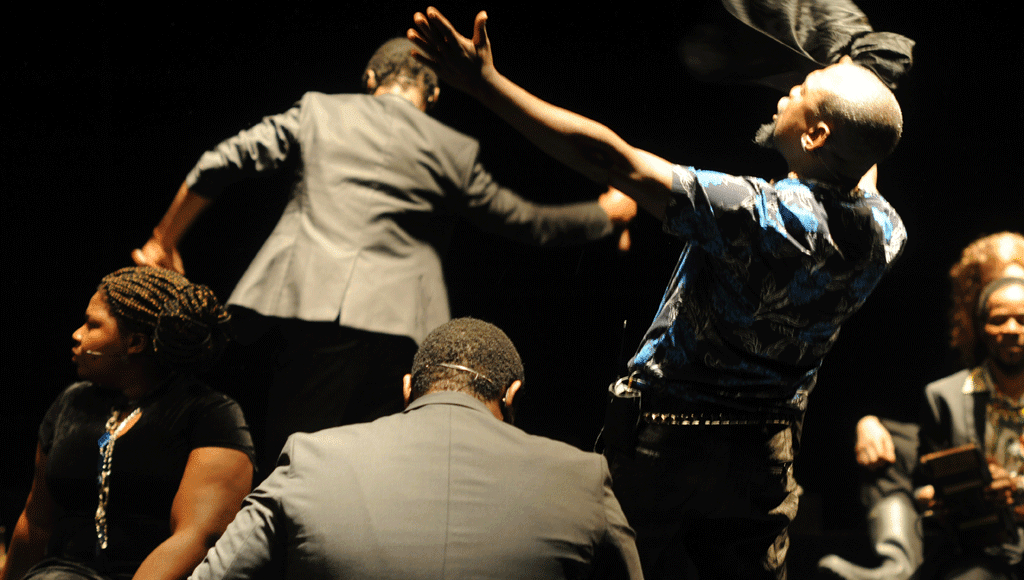

The same could be said of the choreography, which was continually hampered by the set, in this case a scatter of black tomb-like structures that covered the whole stage. There was continuous movement to be sure but more in the form of organised clambering, jumping and formations of small groups than in concerted action or continuous dance. With such a long running time more sustained visual variety was essential to hold the attention of the audience.

Cultural collage is a high ambition and hard to bring off. There is a great concept in play here – fusing different traditions of mourning and commemoration of death that can combine a huge spectrum of moods. However, despite all the skill and careful thought that has gone into this kaleidoscope of African and classical music, with its confronting video backdrop, and constrained sense of movement, what emerges needs tighter structure and more concise discipline to register its full impact.