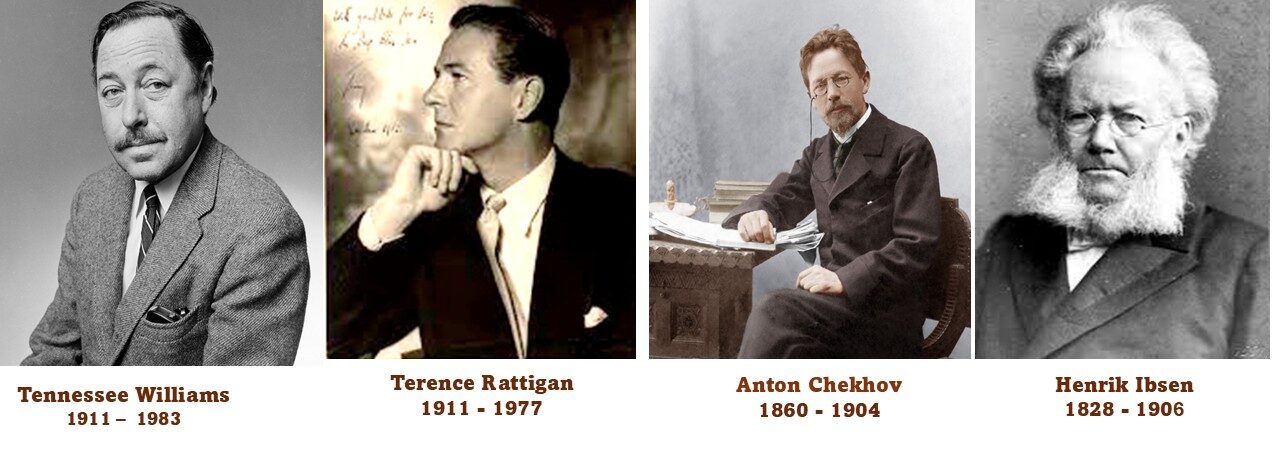

In the landscape of modern drama, few figures loom as poignantly as the woman on the verge — poised between duty and desire, silence and speech, survival and self-erasure. Watching a recent production of Terence Rattigan’s The Deep Blue Sea, (directed by Lindsay Posner), I was struck not only by Hester Collyer’s quiet, devastating struggle to remain alive after love fails her, but by the haunting possibility that what truly lies at the heart of her despair is a grief she cannot name — the absence of a child. The most revealing line in the play comes not from Hester, but from her estranged husband, a judge, who asks: “If we’d been able to have a child… would it have made any difference?” She responds evasively — “To whom?” — and the silence that follows reverberates more powerfully than any confession. Her pain, though private and subdued, echoes across the century in characters like Nora Helmer in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, Sonya in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya, and Blanche DuBois in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. By exploring these four women — not through the lens of feminist triumph or victimhood, but through the emotional texture of their choices — we gain a richer understanding of how the theatre has long been a space for women to speak their hearts, even when the world isn’t listening.

Henrik Ibsen’s A Doll’s House (1879) shocked audiences with its closing moment: Nora Helmer, once the seemingly frivolous and devoted wife, walks out on her husband and children in pursuit of selfhood. This act, unprecedented in its time, became a symbol of feminist awakening and individual liberation. Nora’s journey is one of dawning consciousness — she realises that her marriage has infantilised her, that her worth has been defined by others, and that she has never lived for herself. Ibsen does not portray her as immoral, but as someone morally reborn, discovering that truth and independence are greater virtues than duty or sacrifice. Her rebellion is not against love itself, but against a love that reduces her to a charming possession. Her husband, Torvald Helmer, cannot see her clearly; even his declarations of affection are laced with control, misunderstanding her submission as devotion. When she finally sees the gap between who she is and how she is perceived, her decision to leave becomes both personal and political — a radical assertion of identity in a world that refuses to grant her one.

In contrast to Nora’s defiance, Chekhov’s Sonya in Uncle Vanya (1899) embodies a quieter, more tragic form of emotional endurance. Where Nora acts, Sonya accepts. She harbours deep love for the indifferent Astrov but never confesses her feelings directly; she moves through the play with a kind of stoic devotion to others and a heartbreaking lack of self-regard. Her most famous moment comes at the end, when she comforts the despairing Vanya by assuring him that “we shall rest” in the afterlife — a line so gentle and desolate it feels like a whispered benediction. Chekhov gives her no transformation, no resolution, only a life of quiet service and emotional denial. Sonya’s resignation is not cowardice, but a response shaped by her world: a society that offers no space for rebellion and no reward for unrequited passion. She survives not through freedom, but through faith in future consolation, however abstract.

Terence Rattigan’s Hester Collyer in The Deep Blue Sea (1952) lies somewhere between Nora’s bold exit and Sonya’s quiet surrender. Already estranged from her husband and abandoned by her lover, Freddie, Hester is a woman adrift in a society ill-equipped to acknowledge or contain female emotional intensity. The play opens with her failed suicide attempt — not out of shame, but from a profound sense of futility. Yet what follows is not melodrama, but a slow, deeply internal reckoning. And at its centre may be a maternal absence she cannot bring herself to name — a child never had, a life never nurtured. Rattigan offers only a single clue, through the voice of her husband; Hester does not answer it, and the play leaves that silence untouched. Unlike Nora, Hester does not walk away from her pain; unlike Sonya, she does not spiritualise it. Instead, she chooses to endure — to live, even without resolution or redemption. Rattigan’s portrayal of Hester is deeply modern: she is neither a feminist heroine nor a tragic martyr, but a woman negotiating the limits of love, self-worth, and survival in a restrained, post-war world. Her decision to continue living, quietly and without promise, becomes a muted but powerful form of resistance.

Blanche DuBois, in Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), marks a darker, more volatile turn in this continuum. Blanche arrives in New Orleans fragile, displaced, and clinging to a romanticised past. Her emotional survival depends on illusion, performance, and the hope of tenderness — all of which are dismantled by the brutal realism of Stanley Kowalski. Unlike Hester, Blanche does not quietly endure; she disintegrates. Her collapse is theatrical, total, and public. Williams gives us a woman undone not only by personal heartbreak, but by a culture that offers her no refuge. She is ridiculed for her sensitivity, punished for her desire, and ultimately institutionalised — her final line, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers,” chillingly encapsulates her tragic vulnerability. Blanche’s story is a descent, and a warning: when neither rebellion nor resignation is possible, the psyche itself may fracture.

Together, Nora, Sonya, Hester, and Blanche trace a continuum of female emotional experience in modern theatre. Each lives in a different time and cultural context, yet all confront the limitations placed on women — in love, in autonomy, and in voice. Nora’s act of rebellion is theatrical and political; she refuses to live as a doll in someone else’s house. Sonya, by contrast, accepts her role as invisible caretaker, her hope deferred to an afterlife. Hester falls between them: unable to leave, unable to accept, she survives in the shadow of love and the absence of meaning. And Blanche, teetering on the brink of collapse, represents the terrible cost when love and illusion are no longer enough to hold a fractured self together.

If Ibsen urges action, Chekhov offers consolation, and Rattigan honours persistence, Williams exposes raw vulnerability — where survival is no longer possible without fantasy. These women are not types but emotional truths, each shaped by the climate of her era. Their choices — to leave, to endure, to collapse, or to remain — reflect the evolving ways theatre has allowed women to confront, express, or contain their suffering. The men who surround them — husbands, lovers, or would-be saviours — too often fail to truly see them. Their love is conditional, self-congratulatory, or blind to the women’s emotional realities. Whether Helmer’s patronising affection, Astrov’s indifference, Freddie’s inadequacy, or Stanley’s cruelty — these men cannot or will not acknowledge the full interiority of the women they claim to love. Rattigan’s judge may come closest to glimpsing the truth, but even his insight arrives too late to offer solace.

Watching The Deep Blue Sea today, one feels the depth of Hester Collyer’s pain not in dramatic action, but in withheld speech — a grief that circles around identity, lost possibility, and unspoken longing. Rattigan gives her no catharsis, no epiphany, only the bare choice to live. And yet, in that choice, there is a flicker of autonomy — a decision not to vanish. In revisiting Nora, Sonya, Hester, and Blanche, we witness how modern theatre has offered women a space to confront their emotional entrapment: Nora escapes hers with radical clarity; Sonya bears hers with quiet grace; Hester survives hers with muted strength; and Blanche is destroyed by hers. The men in their lives, for all their love or charm, too often love the idea of the woman — not the truth of her. In giving voice to these truths, these plays do more than trace the wounds of gendered expectation: they insist on the emotional depth of women’s lives, not as symbols or causes, but as deeply human. And in that insistence lies the power of theatre — to hold silence until it speaks.