This play is the creation of Jonathan Lewis, working with and through the Soldiers’ Arts Academy. This remarkable charity recognises that the rehabilitation of those wounded and traumatised in war should encompass and incorporate the arts just as much as physical healing. They aim to offer training and participation in the arts so as to aid a transition to civilian life and also to release creative potential in those who may never have thought of the arts as a medium of self-expression.

The core of the play consists of monologues and scenes workshopped with veterans and their families over a five-year period which seeks to bring out and articulate their real-life experiences of warfare, loss of limbs, PTSD, or inability to integrate back into civilian life. These are very powerful narratives in their own right. But over these searing narratives, Jonathan Lewis has placed a convincing structure in the form of a play about a play. Much of the action is about the bonding and tensions between sixteen veterans and their partners who come together to cooperate in putting on a dramatic representation of their experiences.

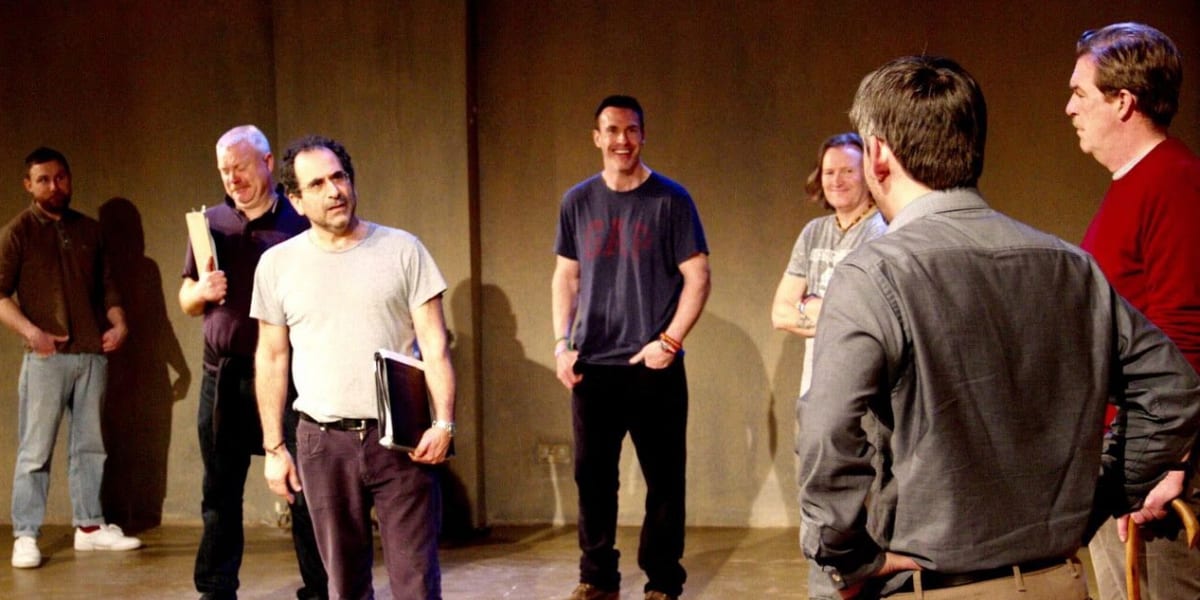

It is something of a slow burn to start with – there is a lot of exposition to get through before the piece catches light in the second half. But it is well worth the wait thanks to the skill of the cast, some of whom are former veterans and others professional actors – but in truth, without the programme notes, one would not know for sure which is which. There are design, musical, dance and technical contributions of note, but essentially it is the work of the cast and the power and presentation of the text that really impresses and moves. It takes both courage and skill to reveal damage and unreconciled, unhealed harm, and this was delivered again and again with rare finesse.

With a large cast each of whom has fine solo moments, as well as ensemble contributions, it is unfair to single out particular contributions but for this reviewer, two scenes stood out above all. Just before the interval, Robert Portal reduced the audience to a rare stillness in his precise, restrained account of a military funeral where his own incapacity was shielded by the self-sacrifice of one of his comrades. Likewise, a rehearsal scene in which Ellie Nunn’s multi-tasking military mum breaks down was uncomfortable viewing, bringing home to us the impossible situation created by a combination of a damaged veteran as a husband and children demanding to be heard and loved.

The play clearly owes quite a bit to Frank McGuinness’ classic play of the 1980s, ‘Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching towards the Somme’. Just as in that play the prevailing ghastliness of the situations and memories is contrasted effectively with the humour and affection and bonding between the characters. Some of the best work here is done by couples exploring in sequence the possibilities and limitations of their connections with wry humour and expressive grace.

Nicholas Clarke and Mark Griffin are very fine in bringing to life characters whose actions make them on the surface quite unsympathetic. Likewise, Rekha John-Cheriyan and Sarah Jane Davis offer fine complex portraits of women placed in impossible situations. Good performances all around. The most fully developed and complex role is that of the director, Harry. David Solomon has a somewhat unsympathetic part to play here, more manipulative than empathetic, at least on the surface. But his character has his own demons to exorcise and that helps to give the play shape and purpose towards the end.

In sum, this play is a powerful statement of emotional truth and resonant witness, but it also works dramatically too, and despite a few rough edges needs no apology as a fine evening at the theatre quite irrespective of this poignant centenary of Remembrance.