Cloud Gate Dance Theatre of Taiwan return to Sadler’s Wells with one of their signature works, first developed by choreographer Lin Hwai-Min in 1984, and much performed around the world since. While the focus of this company is contemporary dance it is important to note that they are also deeply immersed and trained in classical Chinese techniques of meditation, breathing, martial arts, calligraphy and dance. These influences are immediately visible in the aesthetic and emotive language of their creative work.

The opening blackout is pierced by a golden pillar of rice falling from the flies. As the lights go up you see it breaking like a fountain onto the shaven head of a monk who stands stock still, his hands clasped in prayer, for the duration of the main dance sequences – in fact for well over an hour. By the time the evening concludes the mound of rice has risen above his knees.

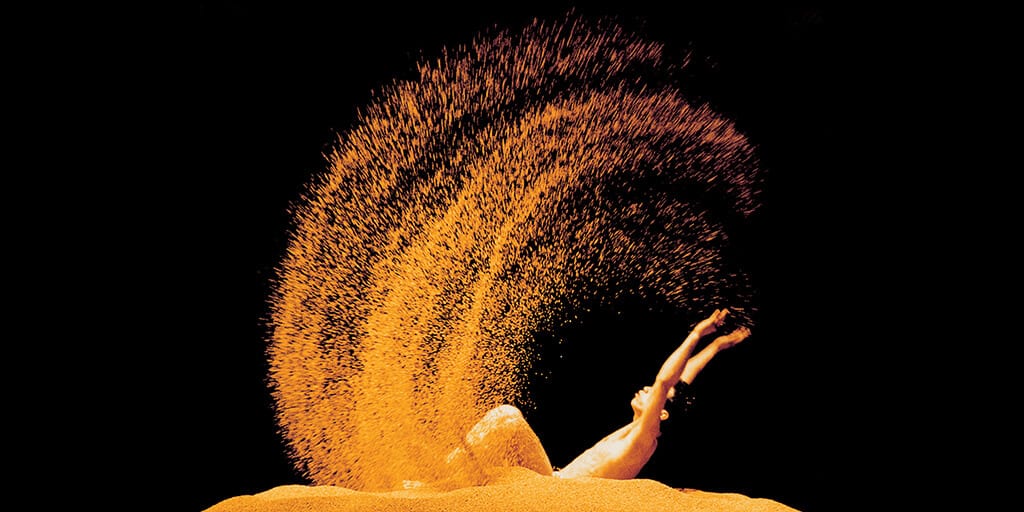

This is only the first of several very striking images that linger long on the retina, and all involving golden rice – three and a half tones of it in all – that falls as rain and then takes different shapes in the work of the dancers – waves, sand, kicked and sprayed around like drops of water and firework bursts, or finally raked into harmonious concentric circles. Crucial to its imaginative power was the luminous, warm, backlighting of Chang Taso-tao’s design.

The predominant concepts are those of pilgrimage and prayer. A cast of twenty or so dancers performs eight sequences with solos interpolated between the group numbers. The evening ends with one figure slowly using a rice rake to impose circular order on the layers of rice. While this mirrored the image of contemplation with which the show began, this final process was too protracted and anti-climactic after the dynamism of what had gone before.

Musical accompaniment took the form of a soundtrack of Georgian folksongs provided by the Rustavi Choir. The hieratic blocks of shifting harmony suited the style and pace of the dancing well and helped convey the timeless, abstract qualities of meditation, searching, prayer and purifying rites of fire and water that structure the piece.

Not that the shapes and themes of the work are always comfortable – far from it. Both singly and in groups the dancers depicted striving and writhing gestures structured by gnarled staffs of pilgrimage to which tinkling bells were attached. In Western terms the dynamic images that came to mind were Michelangelo’s Prisoners struggling to be free of earthly torments or the taut, straining limbs of Goya’s nightmarish dreams, or the sacrificial purgation of the Rite of Spring. Visually though the language was closer to the stylized world of Chinese brush painting as pilgrims toil through an idealized landscape that is alternately hostile and nurturing on the way towards the attainment of Nirvana; or hermits find quietude on isolated mountain tops….

There is more close to the ground movement than normal, so that interaction with the rice is maximized, but the group positions and tableaus were also intensely sculptural, with some lifts and arabesques revealing a debt to Western ballet technique. Above all there was scope for the audience to find space within the interstices of the ballet to reflect on the episodes of spiritual enlightenment depicted and find a personal meaning in the impersonal. After the ninety minutes of the ballet everyone had traveled their own personal journey.