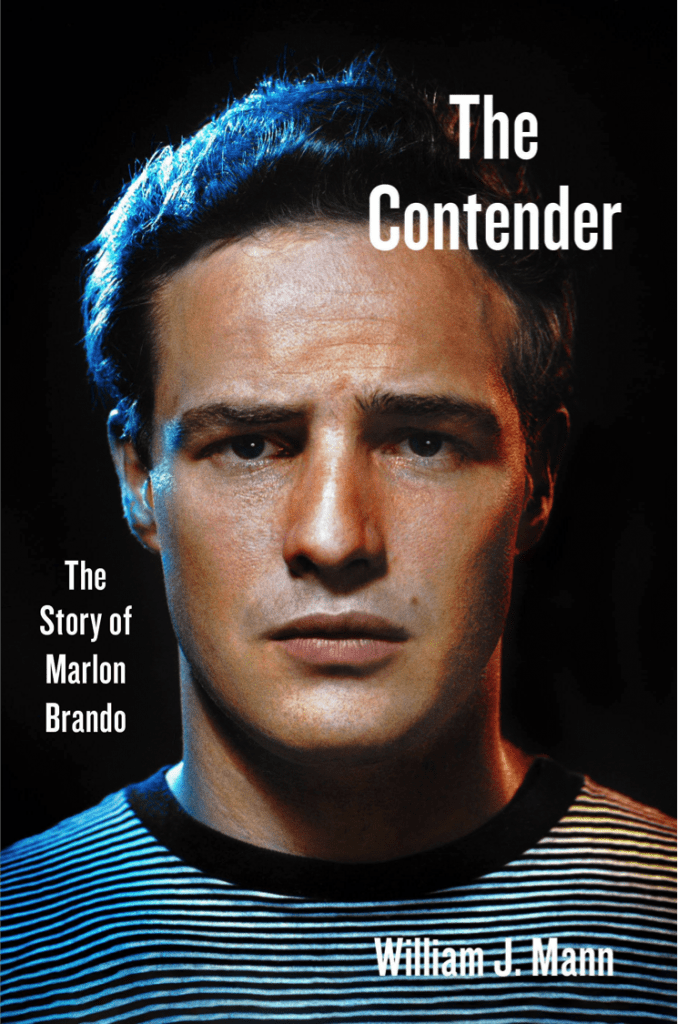

Central to the post-World War II generation of pioneer artists who helped redefine the practice and purpose of theatre, Marlon Brando was considered to be one of the greats. Biographer and historian William J Mann has written a book much admired by Mel Cooper who recommends it not only as a definitive portrait of the man and actor, but as a social history of the theatre and film communities of Brando’s era.

William J Mann has written a brilliant, compelling and utterly convincing about Marlon Brando that I think is important for several reasons both as a biography and as history. It is a must-read for anyone interested in Brando’s career, his acting, his life and the social and historical conditions of American theatre and film in which he developed. It is not just the story of his life; it is also a study of the context of his work from the 1940s through the 1990s and of the many actors and directors and crafts people who were his colleagues and friends: many of them make salient appearances.

Mann has done a scholarly amount of research and conducted numerous important interviews about Brando and he writes the story with great sympathy and understanding, intelligently analysing Brando’s genius, his commitment to developing his craft, his demons, his addiction to sex and his inability to make personal commitments. This is also a rounded portrait of his intellectual interests and approaches; and, above all, his unique and innovative talent. Mann’s thesis is that Brando – certainly along with Montgomery Clift and James Dean – was the leader of a new approach to acting that was profound and hugely influential. Also, he supports Brando’s own contention that he was not a Method actor. The opening sections of the book are exceptional and detailed in describing the true influences on Brando himself, especially the nurturing of Brando by Stella Adler, the group of aspiring actors he met in New York in that period and the Adler family.

For all her grandiosity, Stella also impressed upon her students a deep humility about their craft. An actor’s curtain call, she said, was not about the applause. “Actors bow to their audiences,” she explained, “the way subjects bow to royalty.” Her thinking was summed up in two words: “Actors serve.” Her philosophy, as her grandson Tom Oppenheim would observe, “was always about uplifting humanity,” a credo passed down from the Yiddish theatre of her father. In her acting classes, Stella would show slides of Renaissance paintings or read the letters of Van Gogh “describing fifty different shades of one color,” all in the hope that her students might expand their minds, their hearts, themselves. Actors, in her view, had to be “uplifted human beings,” Oppenheim said. “The growth of an actor and the growth of a human being are synonymous.” The job of the actor, Stella impressed upon her students, “was to lead society into a higher self.”

Once restless, aimless, desultory, Bud [Brando] now sat rapt in the front row, soaking up Stella’s thoughts, words, and ideas like a long-dry sponge. They would define his outlook for the rest of his life.

Mann’s book pivots on the fact that this was the simple truth about the core of Brando’s professional approach and of his continuous quest to find enlightenment and meaning in his personal life. Without glossing over the serious flaws in Brando’s personality that caused him so much anguish, caused others great pain and which have made so many portraits of him appear negative, with utter sympathy, Mann presents the fully rounded man. He also presents clearly for our consideration the story of Brando’s dysfunctional and often traumatic upbringing.

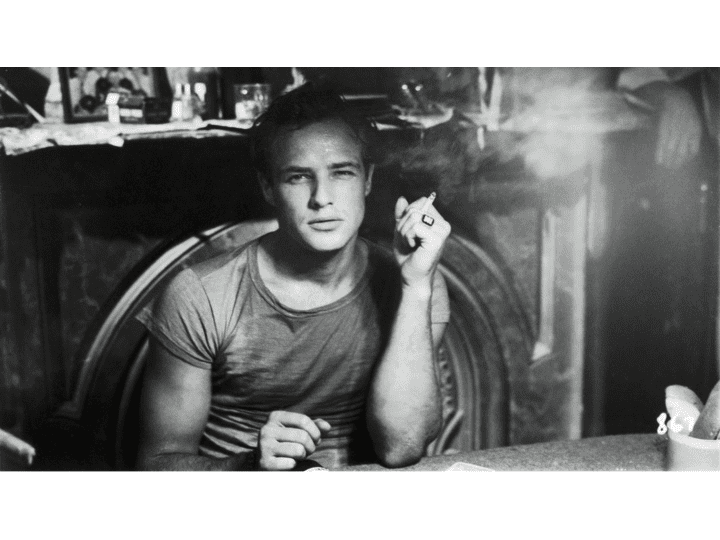

The writing and the structuring of the book are exemplary. Mann explores in wonderful detail all the important and defining roles in Brando’s career from Nels in I Remember Mama through Stanley in A Streetcar Name Desire both on stage and screen and Marc Antony in Julius Caesar. He details with real understanding the important relationship with Elia Kazan that was of both professional and personal centrality to Brando’s development and then the betrayal Brando felt over the McCarthy hearings followed by the making of On the Waterfront and how that reaction informed both the film and Brando’s performance. There are wonderful analyses of his iconic roles: Sayonara, The Godfather, Last Tango in Paris, to name a few; all get their detailed due; but all the other films and portrayals, however obscure some of them are today, get a salient glance at the very least. A myriad of anecdotes build up a portrayal of a troubled but ultimately touching and sympathetic man of immense sensitivity and true acting genius..

As a case in point, [Karl Malden] cited a tiny, telling moment in the taxi scene that wasn’t in any version of the script. It comes right after Terry lowers the gun and Charley sits back. Terry looks away, his left hand coming to his face, and mutters, “Wow.” Just a simple little sound, hardly more than a whisper, made in disbelief that his brother would betray him. “This is where his genius comes through” Malden said. “You know exactly what he’s thinking … he puts himself in the situation.” Marlon wasn’t reciting dialogue; he was inhabiting Terry Malloy, and Terry him, and that’s how you act, not through any method or memorization.

… That simple “wow” – so small, so human, so formidable – exemplifies everything that made Marlon Brando the actor great.

Every aspect of Marlon Brando is here – his strong engagement with the Civil Rights Movement, for instance; his profound concern for Native Americans; his many painful attempts at marriage and family that failed; his appalling treatment of his women; his relationships with his children; and the sad ending. Mann deals with Brando’s complex and fluid sexuality without any prurience, simply as a matter of fact. There is speculation about what might have happened had Brando returned to the stage or lived in New York. There is the full and fascinating story about his one attempt at directing a film (One Eyed Jacks) and how it was taken away from him and, in his view, ruined; and also the ghastly experience of making Mutiny on the Bounty. You also hear from just about everyone who was important to Brando in his life – Rita Moreno, Wally Cox, Ellen Adler, Maureen Stapleton, his directors, his colleagues. Mann’s book also covers a lot of the fun and pranks; and what must have been some sort of bipolar emotional roller coaster that Brando experienced.

At times I had to put the book down, absorb the latest information, and return to it a day or two later. It is a lot to get through (over six hundred pages) and there is no padding. But, in the end, I felt it was worth every moment of my time. Because of this book I now feel a strong sympathy for Marlon Brando the man and a greater admiration for his artistry, his craft, his intellectual curiosity. I feel that what was good about him outweighs the bad. And I am definitely driven back to his movies, wanting to watch again his performances after reading the analyses and anecdotes in this biography. I am now curious about some of the fine performances that Mann describes in what might be some rather lame films.