‘La damnation de Faust’ is, even by Berlioz’ standards, an odd work. Neither opera nor oratorio, but a self-styled ‘dramatic legend’, it is normally confined to the concert platform while striving in its all-encompassing descriptive power for a kind of cinematic hyper-realism that must customarily be disappointed in that setting. It is quite natural, therefore, for any director to want to unleash it on the stage.

However, this too needs to be done with care. While there are long descriptive passages for the orchestra that lend themselves to enactment, the piece is also chorus-heavy, placing limits on realistic narrative, and the individual arias tend to be quirky set-pieces that illustrate aspects of character rather than fitting neatly into any kind of story. A director needs to take risks befitting a work that explores one of the core plots of the Romantic Era, but he also needs to be wary of the pitfalls that can derail Faust’s journey to Hell before it reaches its destination.

The most positive aspects of the evening reside in its musical values. The taxing lead roles all receive excellent, well-calibrated performances and the 64-strong chorus is in splendid form throughout. In the pit Robin Ticciati finds the right balance between restless, fizzing energy and tormented melancholy, and the London Philharmonic responded with verve and finesse. There is often a problem of blending the heavy brassy orchestration and the complex lines of the soloists. Not here. Even in the climatic ‘Ride to the Abyss’, all the music registered its full value with putting anyone under strain.

In the title role Allan Clayton offered a more lyrical Faust than usual, sensitive to the beauties of nature, and very much the frustrated professor worn down by disaffected and boorish students. He also showed greater remorse and awareness for the consequences of his actions than we usually see, matching the delicacy of his singing in the higher tenor register, which so much French opera of this era requires. He was well paired with Julie Boulianne’s Marguerite, who delivered her own arias with an unaffected grace and acted her descent from innocence to degradation and despair with plausible skill. However, the evening really turns on the stylish panache of baritone Christopher Purves as Mephistopheles. He has lots to do in this production, not least in delivering paragraphs of new dialogue devised to open up and help the action along. This could be a tiresome device, but he points the text so well and integrates it all so smoothly with the music, you really cannot see the joins. His singing has wit and menace and he is the most ingratiating master of ceremonies.

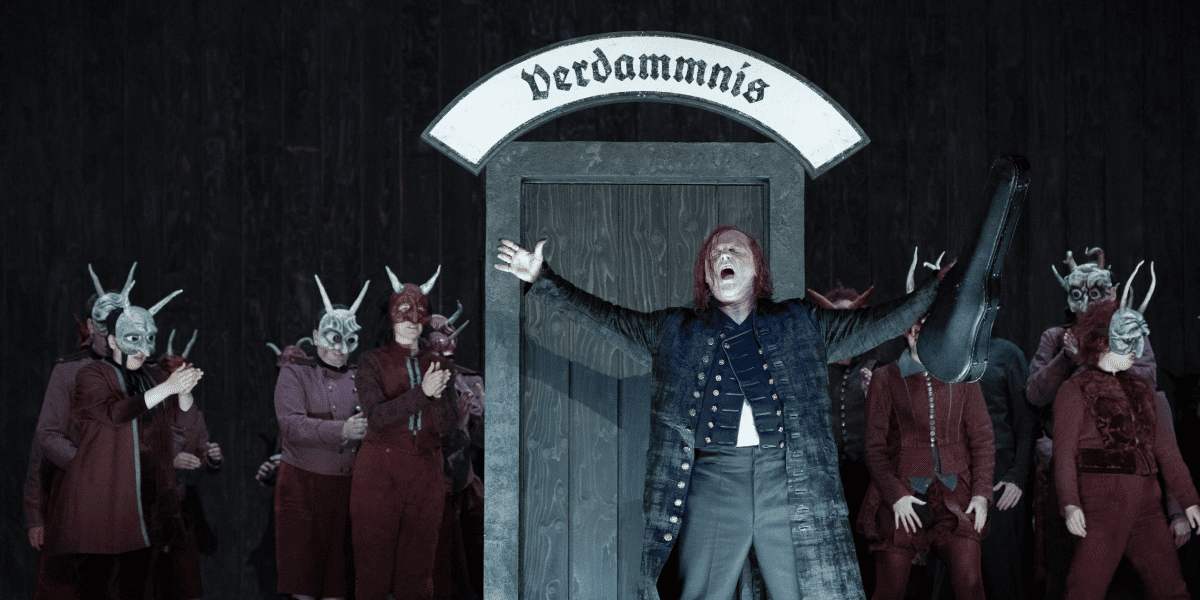

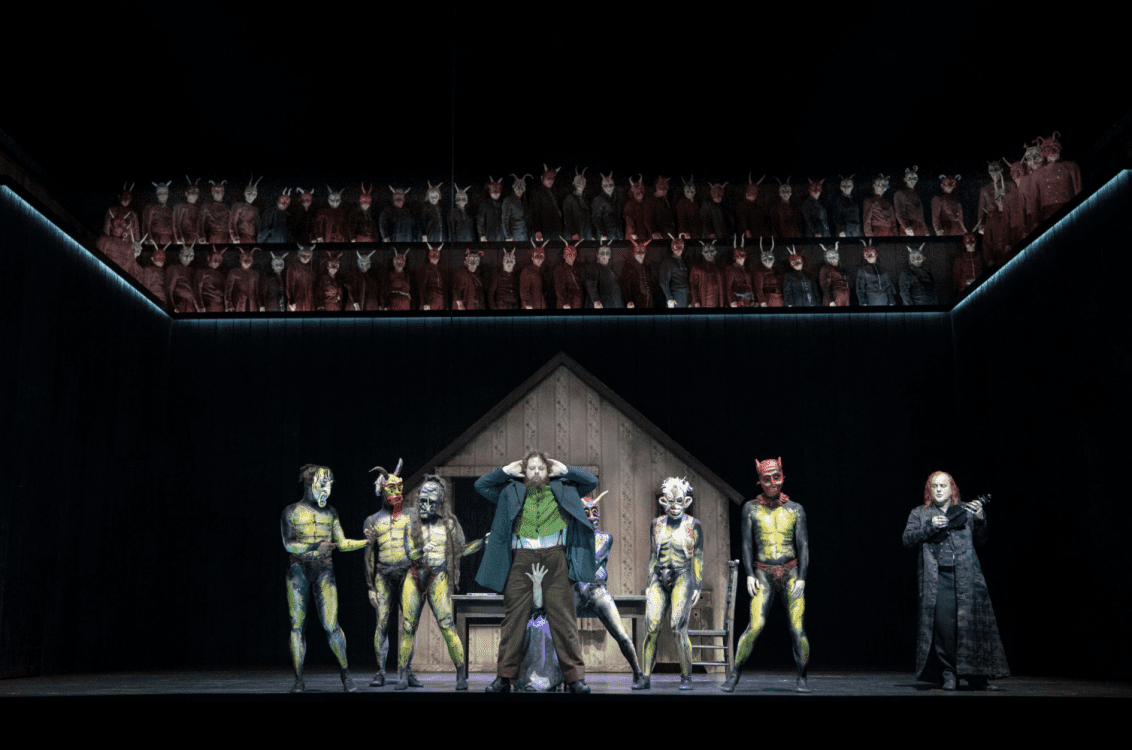

All that said, there are, nevertheless, some real problems with the production itself. Some of the interventions by director Richard Jones succeed whereas others emphatically do not. The decision to place the chorus in a tiered lecture hall all of them wearing masks dealt well with one potential problem – in fact it summoned up memories of the chorus of madmen from the famous Glyndebourne production of ‘The Rake’s Progress’. And the unexpected use of the famous Hungarian March as the backdrop to Faust’s failure to teach Romantic poetry in a military academy was both poignant and funny. But elsewhere Jones simply played too fast and loose with the material in a way that distorted Berlioz’ clear intentions. Scenes were shifted around between the four parts of the work for no compelling reason, and in particular the issue of what ‘redemption’ means at the end of the work is flubbed in two ways: firstly, Marguerite’s ascension to heaven is seen as a projection of Faust’s imagination, not what the composer meant at all; and secondly the work ends with a devilish dance performance to honour Mephistopheles using music from earlier on. Delightful as Sarah Fahie’s choreography is – as always – this was a flat and directionless end to the evening. Indeed Purves had to quieten audience applause before it could begin, such was the sense that work had in fact already come to a conclusion.

There was a lot of attentive detail to note in costume, props and lighting, with many visual themes and motifs recurring to good effect throughout, as they usually do in one of Jones’ productions. But the initial decision to have the action framed in a lecture hall did limit what could be done visually through the set: an inn, a brothel, Faust’s study and Marguerite’s home and decrepit mother could all be suggested; yet when it came to the final approach to Hell the work had all to be done by the music, which was a bit of a missed opportunity.

In a sense everyone just tried too hard to freight each scene with dramatic meaning rather than trusting enough in the brittle brilliance of the work itself. This is a continuously thought-provoking production that receives a top-class musical rendition. But without wanting to be facetious, you could not help being reminded at the end of Eric Morecombe’s famous quip about all the notes being there, but just not in the right order.