Set in rural Suffolk in 1916, this new opera, with music by Richard Knight and words by Norman Welch, tells the story of two sisters, estranged from their nearest relations because of the war, apparently isolated from most human contact and, in the case of the younger sister Violet, sung by Sarah Minns, descending into delusions following news of the battle of the Somme.

Emily, the elder sister, sung by Emma Häll, cares for her Violet such that she tries to reason her out of her mental instability. Mrs Galloway, sung by Miriam Sharrad, pities the pair, and offers to take charge of their upbringing and household. By the end of the opera, as Violet’s neurosis takes ever greater hold and she proclaims that she will give birth to a child of the gods, it becomes clear that her insanity is not all that it might first have seemed to be and that Mrs Galloway’s initial benevolence masks some hidden truths.

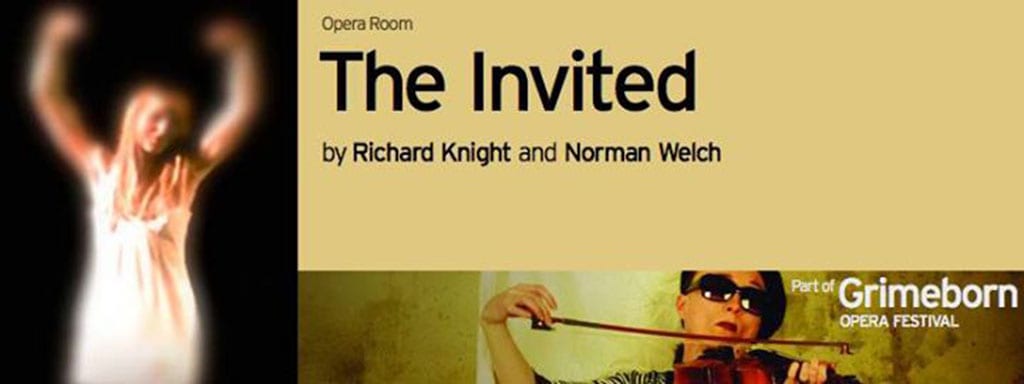

Musically, the opera is energetic and intense, with a warm and dynamic on-stage five-piece orchestra whose interaction with the singers is unfailingly nuanced and engaging. At times the music seems to draw on the Bel canto tradition, and there are plenty of nods too in the direction of Benjamin Britten, though more from the point of view of his use of the Victorian gothic tradition and less in terms of his modernist musical leanings. This is a cleverly devised opera that has the edge over many small-scale productions of larger operatic works in that it is written to scale for a small orchestra and a handful of singers and exploits this opportunity for intimacy to the full.

Among the singers, Emma Häll stands out as having an exceptionally beautiful voice with very wide range and emotional depth; Miriam Sharrad’s performance of Mrs Galloway is subtle and rich. More challenging to perform is the character of Violet, whose descent into madness is the focal point of the piece, and is written in a way which seems at times melodramatic, making it difficult for the audience to fully empathize with her plight and arguably undermining somewhat revelations about her situation towards the end of the production; nevertheless, Sarah Minns gives a spirited and committed performance which is full of panache.

I wonder whether there might be room in the opera for some further exploration of the sister’s relationship – perhaps of more playful sides of their characters and their shared early youth – and there is, perhaps intentionally, little on offer with which the audience can form a mental image, however sketchy, of the world outside of this troubled household; a hint of the broader context might have enriched the production further. Still, I left the theatre feeling buoyed by the creativity and musicality of the production and impressed by the atmosphere and technical brilliance of the performance.