Ηere, nobody lives. Here, nobody remembers, says Mina devastated at the epilogue of The Missing Ones: An Interesting Life. As Katsikonouris’ play reaches its end, one wonders who the missing persons really are: the 1619 men that disappeared during the Turkish invasion in Cyprus in 1974 – maybe the most traumatic issue in modern Cypriot history – or those who survived but forgot, self absorbed as they are in “leading an interesting life”.

Vassilis Katsikonouris, one of the most serious contemporary theatrical voices in Greece, wrote this play in 2005, at a time when Turkey was negotiating its entrance into the European Union. The fate of the missing persons was still unknown, the writer notes, but none of those empowered to raise the issue did anything. Katsikonouris does not deal, however, with the fate of the missing rather than the fate of the living.

In the play, two sisters have lost their brother during the occupation of Northern Cyprus in 1974. Ismene, or Mina, too young at that time to realize what was going on, aimlessly continues her cosmopolitan life in Athens, indulging in her hobbies, pursuing expensive postgraduate studies, travelling frequently around the world – save from Cyprus, where she never returns. The past is properly buried (unlike her presumably dead brother) and the future is not to come, since having a baby is seen more or less as a distraction from “having a good time”. Despoina, her elder sister, unmarried, childless, always dressed in black, bound by a merciless oath her mother forced her to make, visits for a couple of days in order to take part in a protest – in another desperate effort to put pressure to the Turkish government to reveal what has happened to the missing kin. Her insistence on something that happened so long ago seems incomprehensible and meaningless to Petros; Mina’s husband, a career political analyst in a leading newspaper, a market-oriented pragmatist.

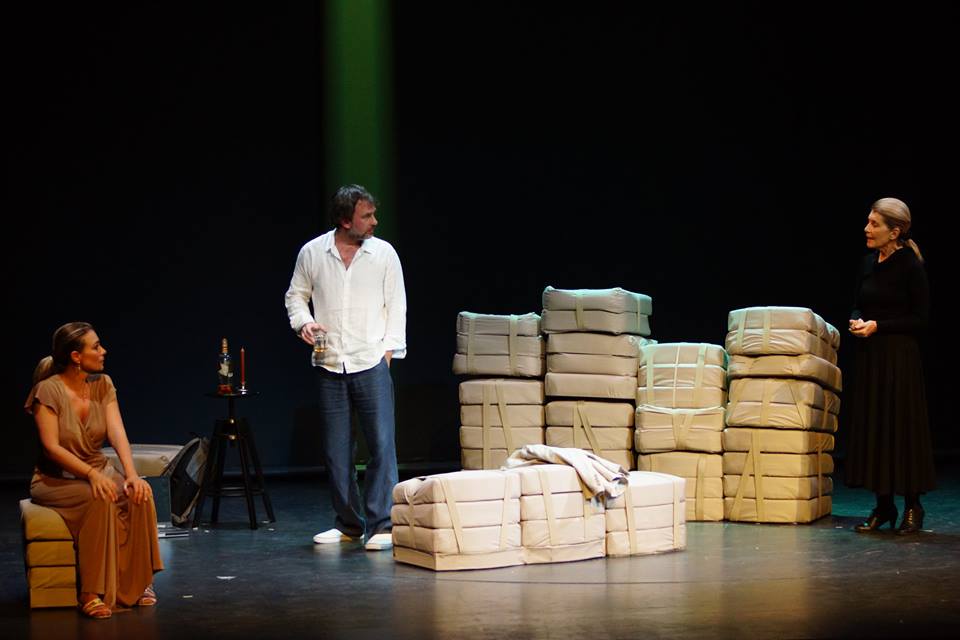

The play features no director; this is a collaborative work as the three members of the cast have directed themselves “preferring”, as noted on the theatre program, “to look for their own interpretative roads in the depiction of the characters”. The outcome is a play that carries the audience along from the very beginning.

Aimilia Ypsilanti, discreetly seated aside, portrays magnificently the kindness and the smiling decency of Despoina. Aleksandros Stavrou, sarcastic, tender and at the same time monstrously cynical is perfect for the role of Petros, who “knows how the system works” and is prepared to be part of it, at the price of his soul. Maria Tsaroucha brings onstage the energy of an open-minded woman, sensitive and thirsty for life, who tries to see both her sister’s and her husband’s truth; unable to identify with either of them, though, she is left alone at the end, mourning for the emptiness of her life.

Although the play is meant to generate thought rather than feeling (tending towards sentimentalism, though, at its closing scene), it touches the heart and soul of the audience. Strongly written and well staged by the cast, it becomes an acute pain in the belly – like the one Petros experiences. Certainly, a powerful wake up call.