Plenty is perhaps not the first word that comes to mind when thinking of the Soviet Union in the 1940s and 50s, but Alexei Abruzov’s “The Promise” does have something of David Hare’s play of that name about it. We open in a freezing (actually, 30 below freezing) Leningrad “housing allocation” (ie flat, or more accurately room) during the 900 day siege of 1941-4. Marat (Tony Eccles) has returned to his childhood home, having been staying with his sister until her house was bombed by the encircling German forces, only to find Lika (Eleri Jones) taking refuge there. Even worse, she has burned several framed photos of his family to keep warm.

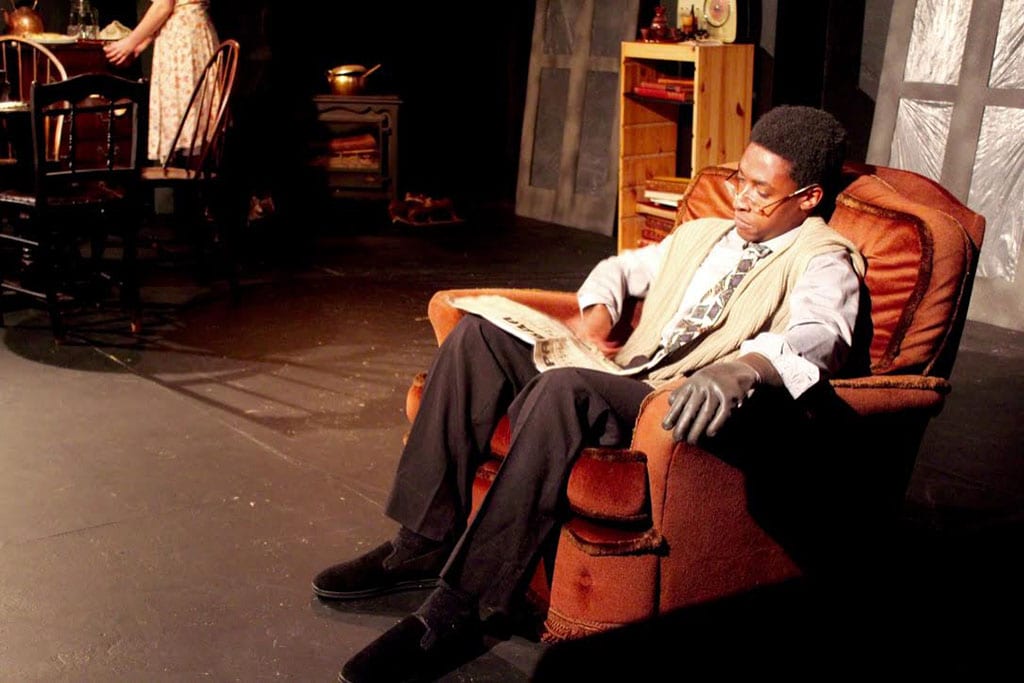

At first she is nervous about their forced cohabitation, wanting to saw the bed in half rather than risk sharing it, but before long they become closer, to the point that they’re dancing together when surprised by the arrival of another refugee, Leonidik (Theo St Claire). The love triangle that this creates persists throughout the other two time periods of the play, 1946 and 1959, as we see the empty space of the White Bear’s stage gradually fill with furniture until it’s more or less comfortable, though still some way short of luxurious. Leonidik comes back from the war with a maimed arm, which Marat selfishly (though astutely) sees as fatal to his hopes with Lika – how can being a “Hero of the Soviet Union” for his work in Intelligence compete with that?

Noel Coward called this a “nearly good play”, and I think he was on the money. Unlike Hare, Abruzov gives us a surprisingly upbeat ending, a gesture of self-sacrifice and a hint that things will be alright now the right people are coupled up, which seems a tad sentimental to a modern audience. If you don’t already know about the horrors of Leningrad during the siege, the play (despite being written long after Stalin’s death, making discussion of such things possible) gives you little sense of them. Moreover it’s very talky, and what might have been an effective theatrical device of confining the whole story to one room in fact becomes quite static and repetitive – either Lika and Marat are interrupted by Leonidik, or Lika and Leonidik are interrupted by Marat (with only three characters, there’s never much suspense about who’s at the door). Garber’s rather flat direction doesn’t help either.

All three actors recently trained at the Drama Centre, where no doubt they were told to be proactive rather than waiting for work to come to them. Good advice, of course, but the problem with theatre companies made up of drama school buddies tends to be that they’re not all at the same level. By far the star here is Jones, captivating and believable as both as the starving 15 year old refugee and the frustrated housewife of more than twice that age. Eccles comes into his own when he lets rip in the final scene, a beast he should let out of its cage more often. But St Claire is only intermittently convincing as the self-loathing anti-Zhivago, the failed poet who refuses to publish his best works and now can no longer write them at all.