The newly commissioned play at he RSC, The Seven Acts of Mercy by Anders Lustgarten is an interesting and successful evening in the theatre. The staging and acting are extremely fine; the company plays well as an ensemble; and the play itself is powerful and fascinating throughout even if somewhat clumsy in its first half. I knew going in that it was a double-plotted vehicle set in two eras – the violent Baroque world of the painter Caravaggio working on a huge and masterful canvas called The Seven Acts of Mercy; and a contemporary England exemplified by a Merseyside story that portrays poorer people suffering from benefits cuts and housing scams, a play set in the world of a Ken Loach film, such as I, Daniel Blake. Surprisingly, the parallels work beautifully; because the emphasis of both sections is on radical questioning of the status quo and the powers of the privileged.

When I emerged from the first half of this play, I was impressed by and interested in the characters in both worlds but not yet totally convinced that the two time frames and stories were not clashing. By the end, I was captivated and totally convinced.

The play is strongly constructed so that the first half sets up characters and situations of some complexity; and the second half is full of necessary pay offs. You can trust the play. You will come out seeing not only how the two tales amplify and echo each other, but also how Lustgarten spins questions around the core themes of compassion, forgiveness, charity and violent self-centredness. He also deals with the concept of Charity both as a Christian requirement and as a potentially patronizing action of the more successful. Just as a patron has to be generous to Caravaggio, Caravaggio has to find it in himself to have the generosity to accept the money and protection of his patron.

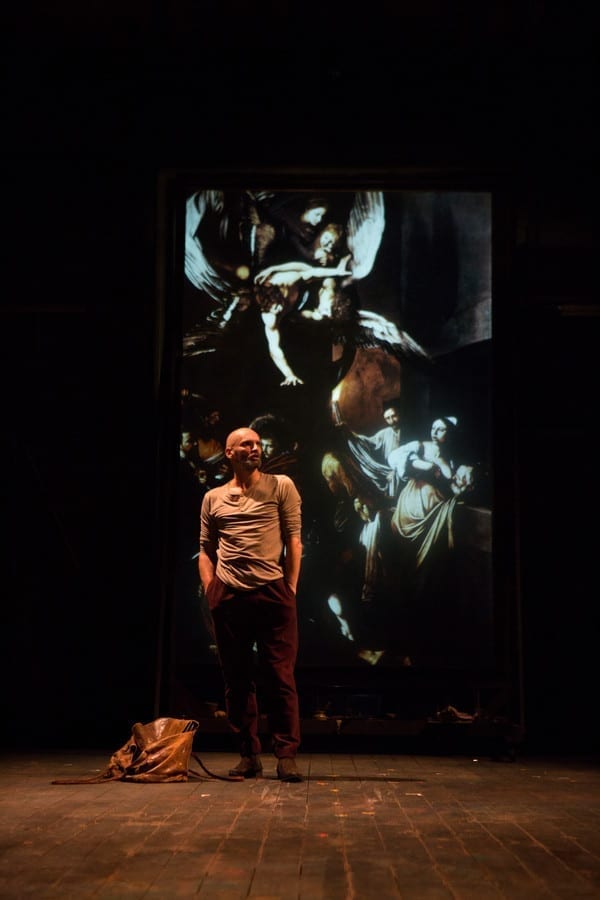

The play makes many references to specific works of art and part of the pleasure of the design is that the various works mentioned are projected so that you can see for yourself. One of the themes of the play contemplates is the role of art, the character of artists, the nature and uses of artistic vision, whether in painting, drawing or taking photographs. Or, of course, in writing a play!

Caravaggio’s painting portrayed the Catholic Church’s seven acts of compassion, such as sheltering the homeless, feeding the hungry, visiting the sick, clothing the naked and, especially in an era of plague, burying the dead. This painting is an altarpiece to this very day in the church of Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples. The story of the making of the painting, the patronage of the Marchese played with strong but intellectually rigorous compassion by Edmund Kingsley, the relationship with a female prostitute and model who also turns out to be Caravaggio’s intellectual and artistic match, a role powerfully showing strength and complexity as portrayed by Allison McKenzie; the politics – commercial, tribal and anti-feminist – is portrayed along with Caravaggio’s pain, anger and love, and all this would be enough material for one interesting play by itself. Patrick O’Kane is completely compelling and believable as the tormented artist and James Corrigan is startlingly attractive and shocking as a pickup who turns out to be an assassin hired for vengeance.

Caravaggio is portrayed very much as a man obsessed with being a voice and representative for the dispossessed. Meantime, in the modern day tale, set in Bootle, Liverpool, the story centre on a dying working class man, sympathetically played by Tom Georgeson, who is trying to bring up his grandson, played brilliantly by T J Jones, to have some appreciation for how the world should be, to have some sort of moral and political sense. He is showing him powerful art for its allegory or symbolism, especially the painting by Caravaggio; and like Caravaggio, the lad has compassion for the dispossessed and uses his mobile phone to take photos of them as his way of making art and making statements. His absent father, Lee, played by Guri Sarossy is, when he returns, not only the man who must take over the bringing up of the son he has never much cared about before, but he urns out to be one of the people working to get holdouts to leave houses so the area can be “regenerated”. The old grandfather,Leon Carragher, is a representative for the kind of radical Labourite that once supported the reforms of Clement Attlee.

In the first half of the play, the portrayal of the Bootle Boys, good and evil, almost seems on the verge of being too polemical so that the actual dramatic situation looks in danger of being overbalanced by Lustgarten’s message. However, this all sorts out in the strong second half, with its shocking turns in the drama and the strong resolutions. No longer are we witnessing sheer polemics. The polemics have provoked real drama.

The play is not perfectly balanced; it is not entirely coherent or easy to follow at times; but it has punch from the opening moments, is memorable visually (full praise to Tom Piper for the design and Charles Balfour for the lighting), and is brilliantly performed under the talented direction of Erica Whyman. Even if some might not agree completely with the political positions of some of its characters, you will be moved by its compassionate view of how the world should be run. The music by Isobel Waller-Bridge also makes a positive contribution. This is a fine and thought-provoking evening of contemporary theatre addressing the issues and characters we are hearing about in the news every night; and the Caravaggio element of the play is just as disturbing and contemporary as the story set in modern day Bootle. It is also very informative and I am determined to read a good book about Caravaggio or see the old Derek Jarman film as soon as I can.