Britten’s The Turn of the Screw was premiered as long ago as 1954, his first project after the relative failure of his coronation opera ‘Gloriana’. But while the latter is irremediably fixed in its own time, the former floats freely, and in so many disturbing ways has gained in contemporary salience and currency. Is it a study of child abuse and evil manipulation of children, or a gothic tale of projection and fantasy by the central character? Or a mixture of the two? It is without doubt one of those works that can readily speak for itself with a rare self-propelled energy, and director Timothy Sheader is wise to let it do so in mainly period Victorian style and setting, with the minimum of directorial intervention.

The key challenge for any production of this ghost story is to maintain and build tension and ambiguous suspense across the evening. A confined space suggests itself rather than the open sightlines and relaxed pastoral setting of this particular theatre. However, the cast and creatives overcome this potential difficulty by putting back the start of the evening to allow twilight gloom to steal upon us as the tone darkens, and relying on the singers and musicians to evoke the world of sinister suggestion that Britten placed in the score. Toby Purser adopts brisk tempi with a fine orchestra drawn from English National Opera, and the cast brilliantly project their lines so that every word counts. There is also a truly wonderful set from Soutra Gilmour, which turns the sinister East Anglian country house, Bly, into a broken down glasshouse on multiple levels, with wooden walkways offering lots of scope for dynamic movement across fenland tussocks in which a piano, and other key props, are, apparently, abandoned.

The six-strong cast (with which another alternates) is uniformly excellent. As the Governess, summoned unexpectedly by a mysterious guardian to take charge of two teenage children whose lives have mysteriously gone awry, Rhian Lois has to move from naïveté through to spreading horror, and perhaps – invention of the unspecified imagined events that creepily insinuate themselves into our minds. She does this with great empathy, tenderness and a necessary touch of hysteria. Alongside her, Sarah Pring, as the housekeeper, Mrs Grose, provides a secure maternal focus, a representative of genial, if blinkered, common sense, largely uncomprehending of the penumbra of evil around her.

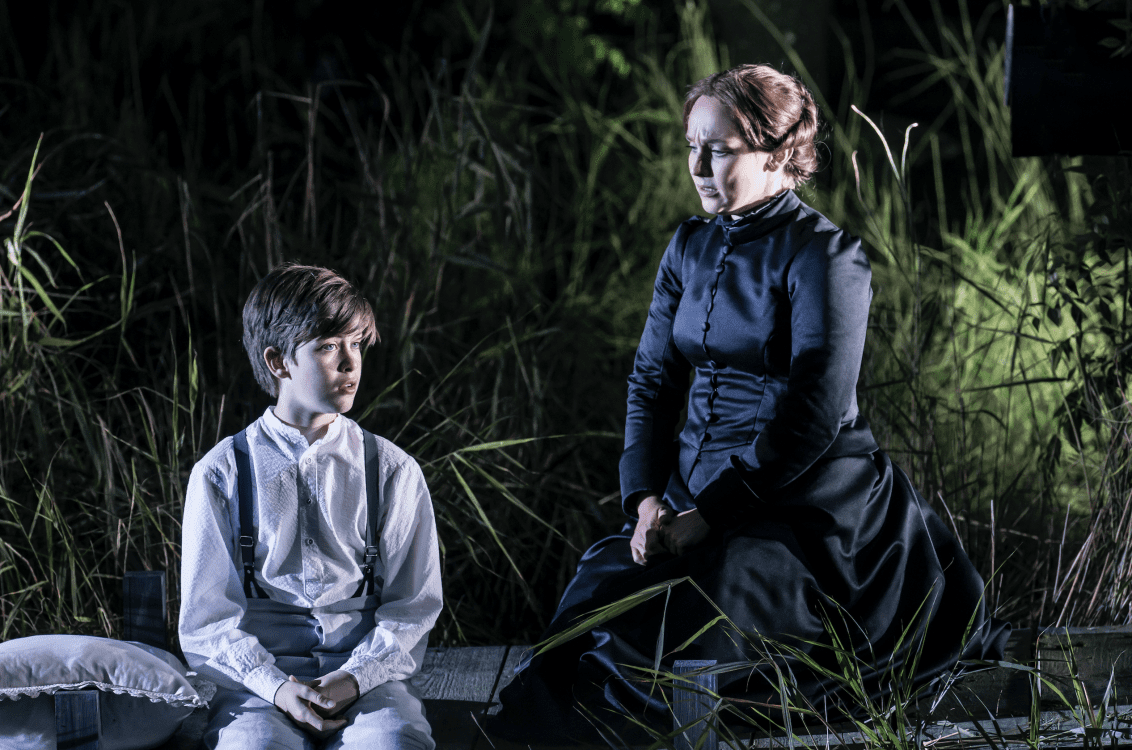

As Peter Quint and Miss Jessel, the malign ghosts that haunt the world of Bly, William Morgan and Rachael Lloyd emerge from within the auditorium and strike the right balance between charm and menace. We believe in their power to beguile and in their likely manipulative purposes for the children. They also carry off the virtuosic aspect of their parts with rare skill. Their former charges, Miles and Flora, are also played with plausibility. You see how the ‘ceremony of innocence is drowned’ in each of them and replaced with a shifting combination of vulnerability, self-disdain and brittle defiance. Ellie Bradbury and Sholto McMillan sing and act with huge confidence and project their roles in this large space with the same skill as those with greater stage experience. The cast is completed by Elgan Llŷr Thomas in the brief role of the Prologue.

This is a work more declamatory than lyrical, and where there is lyricism it is undercut by pathos and a sense of lost content. It is a tribute to the presence of its ambiguous suggestion that the most powerful moments come when exceptional surface beauty is subtly undermined – firstly, the delicate ‘melisma’ of Quint’s first appearance, building from a whisper in the breeze from behind where we sit, is both breath-taking and heart-freezing; and then when the nursery rhyme ‘malo’ emerges, grave and then angry at the end of both the first and second halves we feel the perfect fusion of vulnerability and its malign corruption where ‘secrets and half-formed desires meet’.

This is a very unsettling but wholly authentic evening, and it is hard to see how this opera, ‘difficult’ in the best sense of the term, could be better done – catch it while you can!