Turandot – Puccini’s final opera – is a difficult work to like. Of course. it has some glorious dramatic moments (everyone knows Nessun Dorma by now) and some clever melodic themes capturing a western idea of Chinese music. But the story is more-than-usually implausible and, worse, it is riddled with racist tropes about oriental women and Chinese savagery. This brave production for the Grimeborn Festival by The Opera Makers and Ellandar clearly has noble intentions of re-imagining the story for a modern audience – the production is only partly able to live up to these hopes.

Prince Calaf, his father King Timur, and servant Liu arrive as unrecognised refugees in Peking, where the Emperor’s daughter Princess Turandot is trying to avoid marrying any of the suitors who are pursuing her. Suitors who want to wed her must answer three riddles but, if they fail, they will be beheaded. Calaf sees the princess and instantly falls in love with her. Despite the brutality of this regime, and the public execution of the Prince of Persia, Calaf cannot be dissuaded from his reckless passion. To Turandot’s horror, he guesses the answers to her three riddles. She begs to be spared the indignity of marrying this unknown stranger but the Emperor insists she must stick by her oath. Calaf feels pity for her misery and says that, if she can discover his name by the next day, he will face the axe. Turandot takes extreme measures to discover his name. In the standard version of the story, Liu’s death leads to a change of heart by Turandot and she agrees to wed Calaf. In this production, the ending is much more ambiguous.

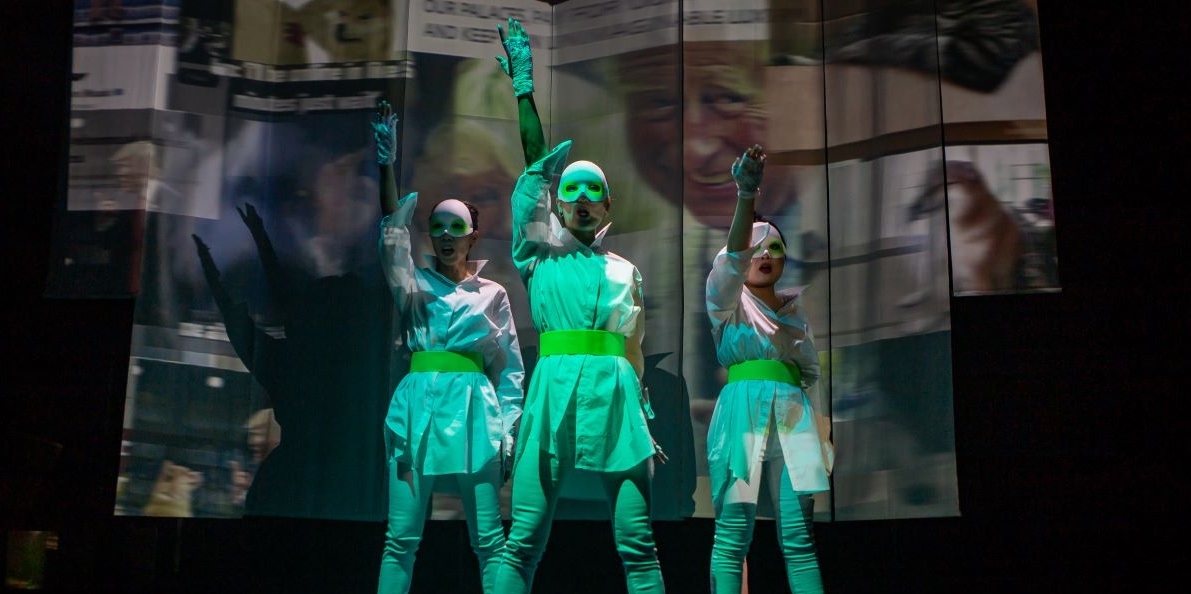

To draw the drama away from the stereotypes that were seemingly common currency in 1925 when the opera was first performed, the directors have imagined Turandot as a fantasy figure drawn from the world of on-line erotica – she first appears as a video projection on the white sheets at the back of the Arcola stage. I should say at this point that the video ‘scenery’ created by Erin Guan is constantly eye-catching and intriguing. When she does finally appear in person, however, it is difficult to not to see her as another stereotype, albeit an up-to-the-moment one. The singers appear in half-face white masks for most of their time on stage and this does have the benefit of removing them from the danger of portrayal as oriental puppets. And the replacement of the dubious Ping, Pang, and Pong of the original by a trio of very fine female singers – Aina Miyagi Magnell, Siyu Chen, and Salome Siu – works well. But the central storyline dilemma – how should we understand the sacrifice of Liu? – is left unresolved. This is all the more frustrating because Heming Li’s performance as Liu is quite outstanding. Her superb soprano voice was the best thing about the musical part of this production. Some of the chorus work was good too – and so brave of the company to get such a large cast of singers onto the tiny Arcola stage – but Reiko Fukuda as Turandot and James Liu as Calaf were both near the limits of their range in the key roles. The piano rendition of the music was finely realised by Panaretos Kyriatzidis and Thomas Ang but, given the richness of Puccini’s writing, particularly for strings, one can only regret that the company’s original intention to use a small orchestral ensemble was impossible to realise.

There were glimpses in this production of what might have been possible had the opera not still been under copyright and I would love to see the the creative team return to piece in a few years time. As it currently stands, it is an interesting but flawed piece of music theatre with some moments of real dramatic power and one that is well worth a trip to the Arcola for Dalston to enjoy for oneself and to provoke discussion about this strange masterpiece.