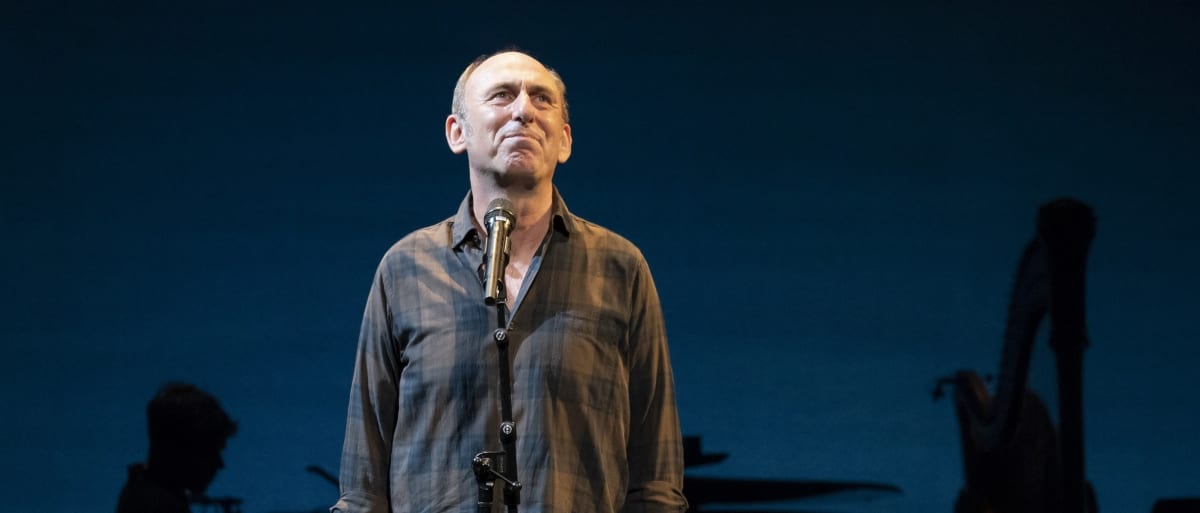

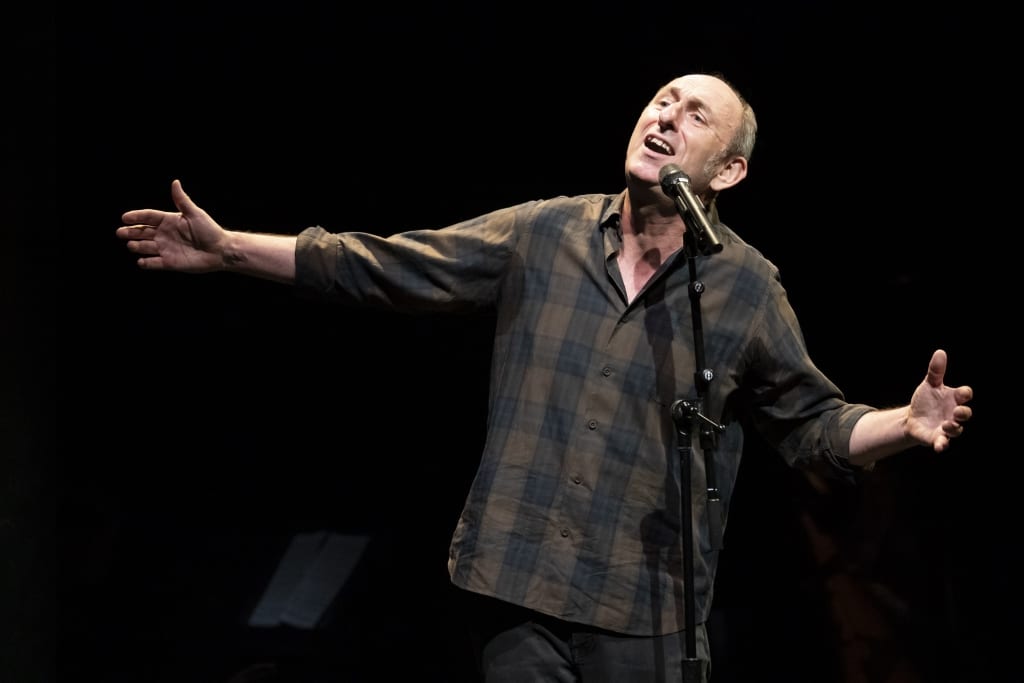

For many who are the products of tempestuous home environments, animals provide a rare instant of peace. Animals serve as a reminder of innocence, an image of inherent goodness, love, and joy in the world, a vital contrast to the dismal reality of their day-to-day. In “We’re Only Alive for a Short Amount of Time,” the new solo musical memoir co-produced by the Public and the Goodman, our beleaguered narrator, David Cale (who wrote and stars in the piece), finds a similar respite among our dumb friends.

Two aspects of this new piece shine with particular brightness. The first is the story, which, to avoid giving it away, features gruesome childhood trauma. The second is Cale’s ability, in his writing, acting (he plays every part), and singing, to summon up vibrant and precise images of the parents responsible for this very trauma. In the latter, he’s buttressed by Robert Falls’ elegant and simple direction.

Cale relates his story primarily through a series of monologues and songs, told from the perspective of each member of his nuclear family. While shifting between characters, Cale is always an amusing and enchanting storyteller, who captures a nearly conspiratorial tone when he speaks. At the same time, he avoids reducing Barbara, his mother, to an emblem of good. Likewise, he refrains from portraying his father, Ron Egleton, as a force of unchecked evil. Given the circumstances of the story, this is no small feat. Instead, both parents seem like drowning swimmers, dragged down by their own egregious progenitors. They flail out, trying to swim, but only succeed in dealing blows to each other and their children.

According to Ron, what brings him and Barbara together is a shared sense of shame about their mothers. Ron’s was a stripper, Barbara’s a prostitute who brought her young daughter along while turning tricks. That, and both Ron and Barbara work in a hat factory. While strong marriages have been built on less, this one combusts early. Soon after marriage, Barbara sacrifices a career as a designer at a rival hat factory to work as a supervisor in one owned by Ron’s father. They disappear into the monotony of life in dreary, working class Luton, a suburb just north of London, a monotony shattered by screams and smashing plates.

Young David seeks an escape from the turmoil of his home life. Even as a youth, David cannot separate escape from healing. In his first attempts to shut out his parents, David saves a plucked and poisoned chicken from its fate as fox bait. Later, David constructs an aviary, where he resuscitates fallen hatchlings by cradling them in his palms and breathing on them. He, in short, finds his respite in animals.

The birds embody an obvious alternative for escape—migration—and for a while, David latches onto this idea. He dreams of gliding away to the United States, to live as a singer, and, eventually, does just that. To an extent, this works: the distance seems to help, especially in comparison to his brother, Simon, described as being, “At home and depressed.”

But he can’t leave home at home—his deceased mother follows him. She appears in the form of women diners at the restaurant where David works, whom he mistakes for his martyred mater. This is because, as both parents boast, parts of them live inside of David. David can’t outrun them anymore than he can outrun himself.

Indeed, the parents’ influence and voice in this show is so great (the show primarily focuses on Barbara) that sometimes it feels like we mostly see David Cale through them. The result is that we see David as an imprint of the parents. Even though David’s body is the only one we contend with, and it serves as the conduit for every other character in the play, I still had the impression of viewing a portrait in negative. Of course, no imprint is perfect—and in some places, David peaks where his mother peaks; in others, something goes wrong and the clay becomes smudged, the image completely obscured.

This might partially explain why the show seems to unravel a bit in the backend. As we follow David across the pond, we move away from the two most compelling characters: the parents. The details on David’s new life in New York are sparse, and we barrel towards a moment of healing transcendence, of escape, which, nestled in a 22-year old flash-forward, feels a bit rushed and unearned. Cale ends the show singing about a feral boy running naked in the moonlight, a reference to an earlier anecdote told about him by his mother. The boy in the song, (in a representatively rhapsodic lyric, with music to match) shouts, “No-one can tame me/’Cause I’m alive!” It’s a hopeful ending in the face of unimaginable hardship. That boy is Cale, and he lives as long as Cale does. But so do the imprints of Ron and Barbara. Perhaps if being alive is what allows us to escape, it’s also what keeps us trapped.