Hadar Galron is a screenwriter, playwright, comedienne and actor well known above all for her sympathetic portrayals of Jewish Orthodox women. She still identifies with the Orthodox tradition but from a critical perspective. She began her life in England and is returning here to tour with this particular play and other work. A previous live recording made in Prague two years ago allows us an advance look at this hour-long monodrama in which she probes the traumas and challenges of the generation who were the children of Holocaust survivors.

The piece takes the semi-autobiographical experiences of Jacob Buchan as the child of Mengele’s secretary and another prisoner and refracts them instead through the life of a middle-aged woman. After a wry opening that notes the never-ending commercial exploitation of news of disaster, and above all of the catastrophe of catastrophes that is the Shoah, Galron’s character Tammy plunges into a detailed evocation of range of characters – her mother, her late father, her late husband, and a prospective Moroccan lover, and all as a part of a broader search for meaning and stable identity within her own life.

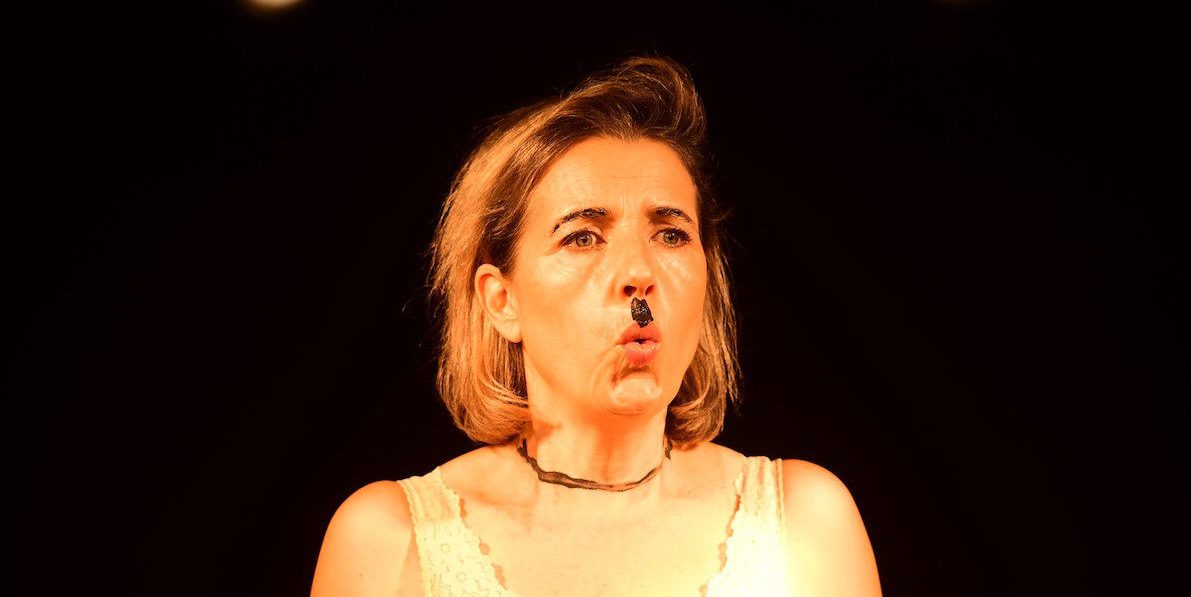

What stands out is the technical skill with which the actor shifts the mood on a sixpence and lets characters emerge with great economy of means. There is little to work with. Just two chairs, an ironing board, a dress on a hanger, and a kettle to make a cup of coffee. Tammy is a painter and so there is a palette of paints too which Galron uses at strategic moments to paint herself with telling emphasis. Apart from that it is through body language, movement, and accents that the actor assembles her key points of reference. The writing is skilful too in the way that information is held back and only gradually revealed, so that the audience has to work a little to join up the dots.

We are sadly familiar with the shock and horror of episodes from the Holocaust and its testament to the quality of the imaginative recreation of the narrative that those evoked here arouse fresh dismay. But it is to the credit of the production that these concentration-camp episodes recounted by the mother are the means to another dramatic end and not an end in themselves. The nub of the play is the limiting effect that her parents’ lives have on Tammy’s own development. Can she find a way to lead a life independent of the burden of her parents’ horrific experiences or is she doomed to be a ‘black hole that swallows anyone who comes close?’ Is it the case that she ‘does not know how to love, and only to please?’

So we learn that marriage and work as secretary to an older academic has not fulfilled her with either children or happiness and that after his death, the circumstances of which remain mysterious, does she have the will and stamina to take a different path despite the internal voice of her mother warning against it? The ending is pleasantly ambiguous, as it should be. We are left with a clear map of the tensions that a child of the Holocaust must carry within that offer little hope of permanent resolution. Perhaps the best to be hoped for is that she can recover her ability to whistle according to her own tune.

The show has a powerful but earned impact despite the distancing effect of the computer monitor and is doubtless overwhelming in a confined small theatre space. The writers deserve credit for finding a new angle of approach to this much travelled territory, and Galron puts it over with a full emotional spectrum of pain, wry humour, and imaginative projection.