If you should ever see one musical, it should probably be 42nd Street, in some incarnation. It’s about the making of a large-cast musical during the economic swamp that was America’s Great Depression, which, oddly, is probably the quintessential backdrop for the fantastical musical genre. In 1933, when the original film was produced, there would have been virtually no distance between the narrative’s musical and the film itself: both tantalised the dreams of the disillusioned masses whilst offering a golden opportunity to young actors. Indeed, it’s not more than a translucent screen which signifies whether action occurs in 42nd Street or ‘Pretty Lady’, the parallel, internal production. The framework allows for razzmatazz unadulterated by meandering plotlines.

Midway-in, a boy in rags finds a sparkling dime and ecstatically proclaims ‘we’re in the money’, prompting the latest version of one of the most famous numbers in musical theatre history. All the starring cast suddenly resemble and embody that glittering dime, clad in a thousand shattered mirrors and a million-odd years of bad luck. That impoverished boy just might have been able to attend one of the cheaper cinemas, which replaced the declining Broadway scene during the Great Depression, when the film was first released. Of course, he’d have no chance getting here into the grandest of theatres, in 2017. That is quite a crucial irony which 42nd Street is aware of but cannot dodge. Saying that, this number does very well what the show does best: it dazzles, it seduces.

The women shine here, in a narrative which – although cutesy in its lyrical archaisms – can un-controversially be labeled as vaguely sexist. After her glorious transition from the ensemble to the lead-role, Peggy Sawyer bizarrely says to director Julian Marsh: ‘you were inside me pulling the strings’, abandoning her agency. Nevertheless, Clare Halse plays Sawyer and scores some of the freest laughs of the evening.

And in ‘Keep Young and Beautiful’ comes the notorious chorus, ‘what’s cute about a little cutie is her beauty not her brains’ which, in fairness, does make clear where the priorities of this show lay: in spectacle for spectacle sake, not for dissection. There is a vague feeling of self-ridicule here without by any means rejecting the puerile sentiment of the lyrics.

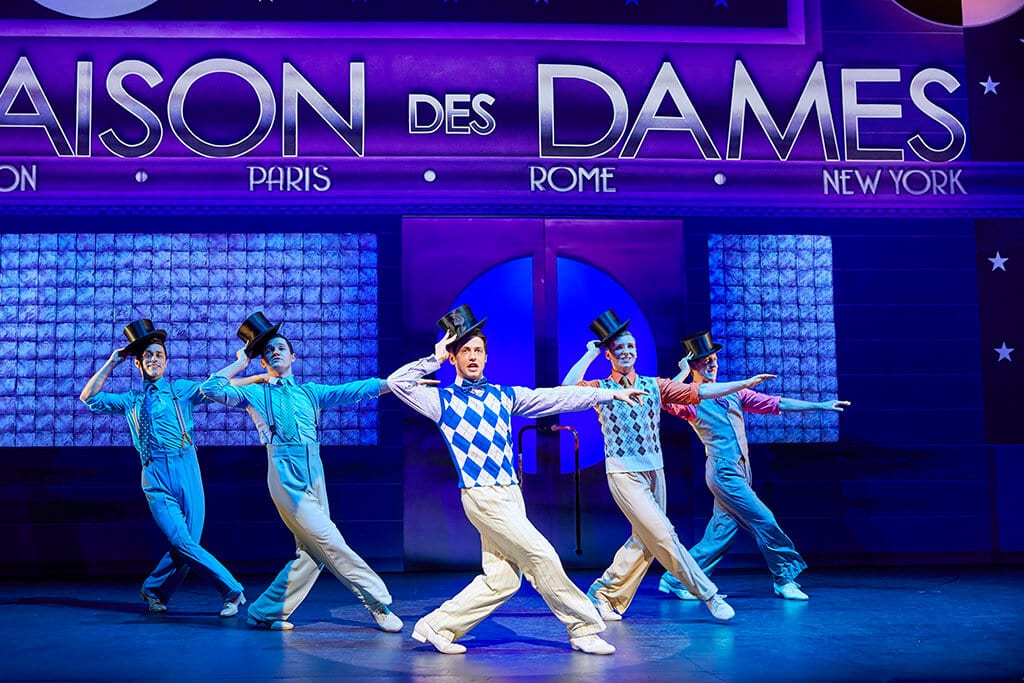

Of course, the dancing and production are stunning. As they absolutely must be in a song-and-dance about a hugely successful song-and-dance. A giant vanity mirror reflects a kind of rotating synchronised-swimming routine – and who could complain for seeing a synchronised swimming routine in the dry, warm, chlorine-less splendor of the Theatre Royal.

The energy is well weighted, and each half’s finales are brilliantly explosive. It’s hard to imagine many people going home feeling hungry for more. And yet, with the resources and responsibility afforded this production, it doesn’t feel completely satisfying. Simultaneously, its ambition is gigantic and orthodox.