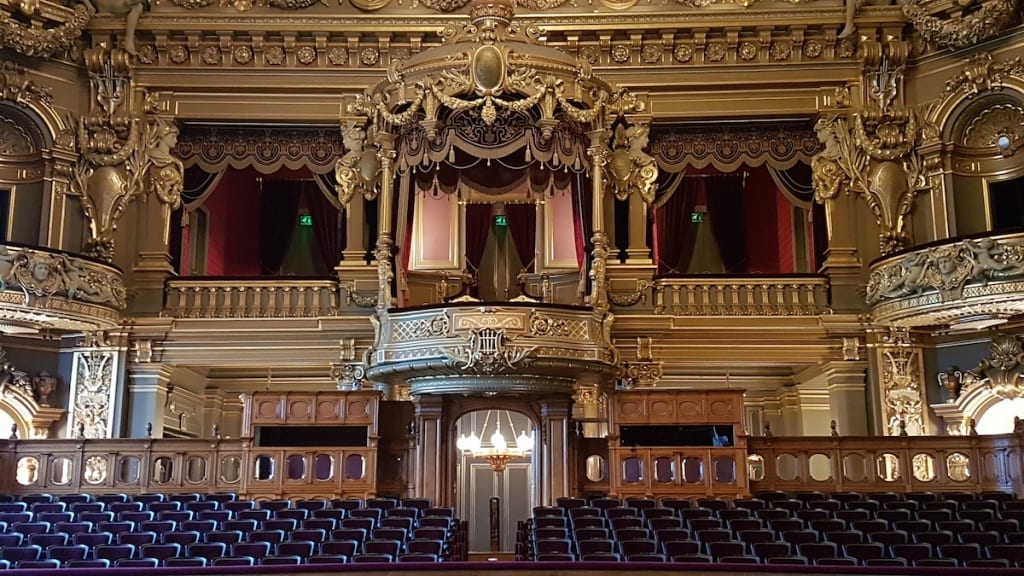

At the Monaco Opera House, the 2019 season opens with Donizetti’s opera ‘Lucia di Lammermoor’, known as a tragic drama in two parts. Roberto Abbado conducts the Monte Carlo orchestra, and Jean-Louis Grinda, the artistic director of the Opera House, directs this production. The end result is an inspired evening of sheer excellence.

Away from the splendour of the Opera House and its renowned neighbour – Monte Carlo Casino – in a large, yet cosy, dressing room, I met Maestro Roberto Abbado, 20 minutes before he is to mount the podium to lead the evening’s performance in front of the audience from France and elsewhere. I must have been more anxious about the time squeeze, more than he was. His cheerful and friendly manner put me at ease and we chatted as if he had no time constraints.

He is an Italian opera and symphonic music conductor who enjoys conducting either. He loves Verdi but hastens to add ‘that without Donizetti, Verdi could not have developed the way he did’. He adores Wagner but admits that he has conducted only one of Wagner’s operas – Parsifal, Wagner’s final masterpiece. ‘It was one of the most beautiful experiences in my life’ he adds. He points out that a number of the world-leading Wagner conductors are Jewish despite the fact that he is not performed in Israel. Naturally, when conducting symphonies, Beethoven tops the list. There is, of course, a great difference between conducting an opera and a symphony – requirements differ and the needed attention to details differs.

To find out a little about his journey through music and his background, Roberto Abbado replies with a bright and fresh voice. He affectionately recalls something of his childhood. Music seems to have been the oxygen in the Abbado household. Roberto grew up where he ‘breathed music from the first very first day’ of his life. His father, Marcello Abbado, the Italian composer and pianist, now 93 years old, would daily practise the piano at home. Roberto recalls with great joy the excitement he and his brother Adriano experienced, lying under the piano, and feeling the music reverberate through their bodies, during their father’s piano practice. Roberto recalls that experience with youthful excitement of happy recollection, adding ‘there was lots of Debussy and Mozart’.

He says with a smile that his grandfather, with the ‘important name’ of Michelangelo’, was the first professional musician in the family. He was a violinist and a very good teacher. Many of his students eventually became concertmasters and leading musicians. Prior to him, there was a string of amateur musicians, so music is very much in the DNA of the Abbado family. His mother’s branch of the family, he adds with a smile, ‘there were a few amateur musicians’. He points out that his great-grandmother was Jewish, ‘Yes, her name wars a Teresa Geiger’. The family came from the Veneto area, namely, northeast Italy and with some Austrian links.

Despite being surrounded by music the young Roberto favoured electronic and mechanical things, until, that is, at the age of 15 a proposal from a teacher changed his life. The young Abbado was at the time a pupil at ‘The Conservatorio Statale di Musica “Gioachino Rossini’ in Pesaro, Rossini’s birthplace. A teacher of solfège, using the Carl Orff method -‘he was teaching how to sing in a choir and how to play small percussion instruments’, the teacher asked the young Roberto to conduct the end-of-year concert. It was a daunting challenge as the young Roberto Abbado had no idea how to conduct. The teacher reassured him ‘don’t worry, I will teach you. So I went through my very first rehearsal if I might call it that and I fell in love with music immediately, although at that time I was playing the piano quite well but, the piano never captivated my heart as conducting a chorus and some percussion instruments did right away’.

That debut as a young conductor was a landmark in his life. He recalls vividly how he couldn’t sleep: ‘I stayed awake the entire night because I felt in love and you can imagine at the age of 15. It is the love for music that has never left me and is still fills me today. I still I feel exactly the same as that night.’

From Pesaro to Milano at the Conservatory Milan, Abbado furthered his study of conducting. His uncle, Claudio Abbado, served as music director of the La Scala Opera House. Here, the gates of ultimate training opened for him. All the students studying to be conductors were given access to rehearsals and performances. The young Abbado recalls the experience he encountered with world-leading conductors, the amazing access he and his colleagues had to all orchestra rehearsals. That opportunity to listen to the world’s leading conductors offered him the most fantastic lessons and opportunities.

It is his encounter with the superb teacher, Franco Ferrara (1911-1985) that Abbado regards as another turning point in his career. Ferrara was a man whose brilliant career as a conductor was cut short by epileptic fits, which forced him to abandon conducting and teach young aspiring conductors instead. He points out that ‘many of today’s greatest conductors were his pupils’.

Abbado, a much-admired conductor, explains with charm the main role of a conductor: ‘The most important task for a conductor is to be able to bring members of the orchestra together, in a wider sense of the word ‘together’ and ‘I am not talking about the synchronizing of the sounds, which is also part of our job, which is getting every musician to play together. To do so is to bring the personalities of the musicians together, to establish a musical relationship with the whole team – musicians, chorus and director’.

It is the conductor who has to have his/her interpretation of the musical piece, from their reading of the libretto and music score. They have to offer it to the musicians and the rest of the team. He elaborates by pointing out that ‘the text may be dramatic and the libretto is serious or has sarcasm. A composer starts from the drama – composer and librettist come together to give the drama the desired meaning. Take just the music, it can be funny or happy, but in conjunction with the text, it is all a very different story. The words in the libretto can give the conductor the right interpretation of what the music means’ he explains. To highlight this point he takes Lucia di Lammermoor as an example. ‘There are two parts to the opera. The end of the first part, a long piece of 20 minutes, starts with a chorus, the music quite lively and happy, but the drama is in the actual libretto. The guests are coming to Lucia’s wedding. Lucia is not going to marry the guy that she loves. She is forced or tricked into marrying somebody that she has never met in her life. This is a political reality in which Lucia has to sacrifice her love, her life. All those people are invited to a wedding party, but they know that the groom is not Lucia’s choice for a husband. So the music is superficially lively and happy but the drama in the libretto throws a different meaning on the whole scene and fires new sparks into the music’.

Abbado points out that one of the important technical issues that a conductor has to grapple with is to ensure the singer’s voice is heard by the audience and is not drowned by the orchestra. ‘The orchestra must play softly enough for the voice to be heard, but loud enough to maintain body and energy. That is not always easy’ he adds.

Within the very limited time, we met he manages to point out different aspects of the role of a conductor. It is amazing how much goes into every production that needs to be closely managed and rehearsed. ‘Hard to believe, but to conduct an opera – there are words, chorus, costumes, singers dressed in full dress – the full dress is without the orchestra, but only has a piano accompaniment to put the cast at some ease’ says getting up to rush to the podium, where the orchestra is patiently waiting.

The last call over the tannoy is clearly heard.