Hans Fallada’s Alone in Berlin (Jeder stirbt fuer sich allein was the original German title) was, perhaps, the first novel to deal with the internal resistance to the Nazis in Germany itself during World War II. Published successfully in 1947 in German, it took some time to be translated into English. Alistair Beaton, who has a considerable career of playwriting, translating and adapting behind him, has now put the story on the stage.

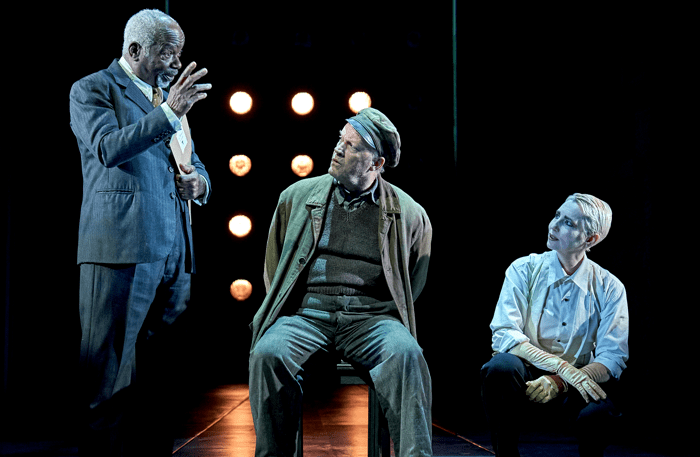

The premiere of Alistair Beaton’s new play was on Wednesday 12 February 2020 at the Royal and Derngate at Northhampton. After finishing its run there it will tour to the Theatre Royal, York and then to the Oxford Playhouse. I was able to have a conversation with Alistair soon after the premiere of his adaptation. I began by asking if he had decided to put this material on the stage at this time because it seemed relevant in some way to today’s politics.

“No,” he replied, “the desire to adapt this novel was in no way directly because of today’s politics. Indeed, I was motivated because I have loved this book for years.” He went on to explain that he speaks fluent German as well as Russian and has spent periods of time living in Berlin, a city which he loves and the history of which fascinates him. For this adaptation he didn’t use the English translation but returned to the original German text.

“Berlin was always an important part of my life,” he pointed out. “West Berlin was, indeed, the first foreign capital I visited in my late teens. But as it happens, I didn’t know about this novel till ten years ago, even though it was published with reasonable success at the end of World War II.”

“What impressed you about the book when you finally got to read it?” I asked.

“It struck me as a book that says everything about the ultimate questions of good and evil and how do you live it in an era that is split between the two. Adapting it was a challenge, but not just because of the difficult themes it covers It’s a huge, energetic and sprawling book.”

“Didn’t you worry that it was too episodic for a stage play, then?”

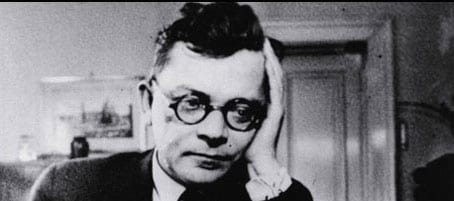

“The writer, Hans Fallada (his pseudonym, his real name but Rudolf Wilhelm Ditzen) had a real challenge on his hands because the story is about two people who are anti-heroic heroes and the story is very un-dramatic in a way. The ultimate story is that they paid for their protests with their lives. The book needed a wider canvas than just this couple staging a small scale and somewhat domestic resistance to the Nazis to make it dramatically interesting. It is a long novel full of a lot of low life secondary characters, stool pigeons, thieves and whores. Short of having over forty actors and five hours for staging the play, I decided I had to distil the original material down to its essence.”

“And what do you think that essence is?” I wondered.

“A very ordinary couple who voted for Hitler and then find themselves are provoked by the loss of their much-loved son during the invasion of France and decide they were wrong about the Nazis and now have to do something about this evil regime. They must speak up, tell the truth as they now perceive it. For me there is a touching simplicity about them, a lovely honesty planted at the heart of this story. So the couple, Otto and Anna, start writing cards to leave all over Berlin warning people about the Nazis, asking for the people to resist however passively. Of course, they think that the cards are going to be passed around. But nearly all of their cards are handed in to the authorities. Of the nearly 300 cards and letters they wrote and distributed only 18 cards don’t get handed in to the Gestapo. For me these people did have a kind of transcendental quality. What appears to be a pointless gesture is actually a moral act that transforms them into heroes.”

“I know that Hans Fallada had a pretty sordid and rather disreputable life. How much of his novel relates to his own experiences?”

“The novel is based upon a true story of a real couple. Hans Fallada, who wrote the novel, returned to Berlin from the countryside at the end of the war and a friend of his working in the Soviet sector dumped a file on his desk one day. ‘Here’s your next novel,’ he announced. He had given Fallada the actual Gestapo file on the couple, Otto and Elise Hampel. Fallada read the file and started writing. He was already very ill and died not long after the book was published but amazingly he seems to have found the energy for this project. He changed a few names and details and created the story of the extra characters, and it was in those subplots where he drew more upon his own experiences. But I was most interested in the essential heart of this ordinary gesture of ordinary people who become heroes. The novel came out 1947 in Germany and though it was not a failure the divided Germany of that time was not ready for it yet. It was published and sold respectably, I think, but it was not a huge best seller. And then maybe about ten years ago it came out in English and that became a huge and remarkable success in English speaking countries which in its turn caused the Germans to renew interest it and new versions of the book were published in German again.”

“But you decided not to us the English translation of a few years ago,” I averred.

“No. Everything in the play is translated by me directly from the original. I wanted to do my own dialogue. Fallada uses a lot of Berlin dialect that I wanted to translate for myself. Another thing I found fascinating about the book is the low life characters who are ducking and diving through life and surviving even under the Nazis. It reminded me that under Totalitarian regimes most people are just trying to get by. They are not thinking about what is bad or what is good, what is moral, they are just thinking about trying to get by. That humanises the story. For me the danger in writing creatively about the Nazis is that you portray them as a monolith of evil for twelve years. They become only these bad people who did bad things. And yes, they did in the end. But it did not start out that way. It was a series of incremental steps inuring the public to what they wanted, and that comes through in Fallada’s book too. So it is not just about Nazi Germany but also about every time and every place.”

“Has this always been a viewpoint of yours?” I wondered.

“In my own plays I write a lot about power and politics and these things do fascinate me. The new right wing is very sinister and has evil possibilities. But I want the audience to make that connection for themselves if they want to. The dialogue in my adaptation is a mixture of my own invention and things I got from Fallada but there is a point where one character is talking with Otto that I think somehow is the crux.

Otto: I understand. But what can we do, with all those millions believing in him? And they’ll believe in him even more now we’ve conquered France.

Trudi: We can tell people they’re being lied to.

Otto: Nobody minds being lied to any more, Trudi. Nobody cares about the truth. If the government offers them victories, glory, national pride, people will go along with just about anything.

Every time that speech is made in the theatre there’s an intake of breath in the audience. That’s just like now, they seem to be thinking.”

I wondered how Alistair had come to visit Berlin as a youngster in the first place.

He laughed. “I was 16 and won an essay competition that had been set by the West Berlin Senate to write about modern Germany. And I got a week-long visit to Berlin as a prize. I’m just a simple boy from Glasgow so I was on a plane for the time in my life and I got to stay in a hotel for the first time.”

“And did you get along well in the city right off?” I wondered.

“My German was not bad even then because I started studying the language at 11. I was very lucky. We could choose between German and Latin and about 320 people in my school took Latin and only five took German, so we had a lot of attention and very good tutoring. Also we had an inspiring teacher.”

“And now that you are seeing the show on the stage, are you happy with the result?”

“It’s a difficult tightrope to walk between being faithful and honouring the book while offering the audience a good evening in the theatre. I find that I’m always walking that line. My commitment in the end is to the people in the theatre. You need to respect the book but not treat it with reverence. Therefore in many ways people will find that it’s different from the novel but I hope that it provides a good evening in the theatre. But I also hope and believe that it reflects and does justice to the spirit at the heart of the novel”