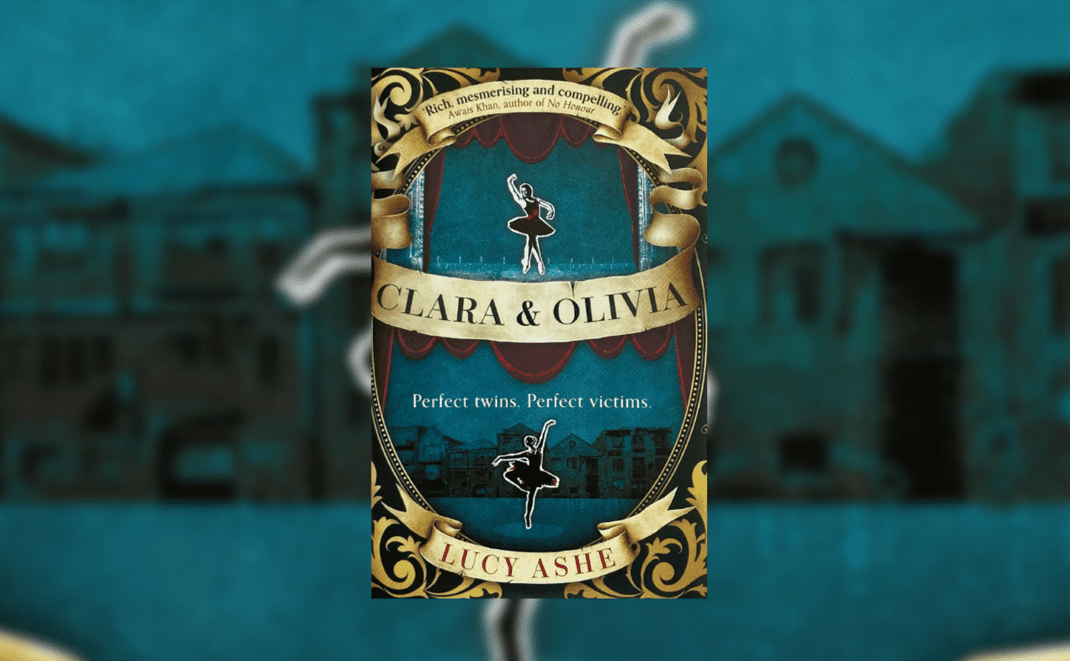

by Lucy Ashe

This original and exquisitely written novel is a highly accomplished debut from Lucy Ashe. Lucy trained at the Royal Ballet School, so it is written from a insider’s perspective; but it also is the work of someone who has taught English literature at a high level for many years, and therefore embodies carefully considered and artistic decisions as to how to present the world of English ballet in 1933 to contemporary audiences.

We find ourselves plunged into the world of the Vic-Wells Ballet in their early years at Sadler’s Wells, focused on rehearsals for Delibes’ ballet ‘Coppélia’. We encounter Ninette de Valois, Constant Lambert, Lydia Lopokova, and many other storied names from the history of a company that eventually became the Royal Ballet and the Royal Ballet School. Into this impeccably researched and vividly evoked framework are inserted four wholly fictional characters around whom the action centres. There are two identical twins, Clara and Olivia Marionetta, both dancers in the ‘corps de ballet’, and two men, Samuel Steward and Nathan Howell, each of whom is involved with one of the sisters.

All four of the characters are carefully, plausibly and memorably delineated. Clara is the sister with charm and engaging personality who excels in character dances; whereas Olivia is a shy perfectionist, with greater classical poise than her sister, but less stage presence and self-assertion. Samuel Steward is an apprentice shoe maker for the firm that makes all the pointe shoes for the ballet dancers, who becomes obsessed with Olivia and her dancing; and Nathan, the rehearsal pianist for the ballet, is equally fascinated by Clara. Each chapter is written from the perspective of one of the four main protagonists, mostly in forward narrative, and sometimes as different takes on the same events.

A fifth major character is inter-war London. The descriptive writing is measured and precisely evocative of Sadler’s Wells, Clerkenwell and Exmouth Market before shifting gears and location in the final chapters to a heightened gothic evocation of the still, deep and murky waters of the Regent’s Canal around Sturt’s Lock. It is as though you are taken on a prose equivalent of one of those early silent movies depicting a barge’s sluggish sepia journey through the still working wharves of a lost London.

A brief review cannot do justice to the many varied textures of the writing and the careful layering of symbolism, particularly the parallels between the plot of ‘Coppélia’ and the experiences and motivations of the lead characters. There is also a very skilful modulation of tone in the final third of the book into the genre of ‘film noir’ thriller. However, what lingers longest in the memory is the author’s success in evoking what the day-to-day routine of ballet rehearsal is like. While much is written about the final outcomes and the great banner successes, we are far less aware of what has gone into those achievements and the intense training and practice routines required to make it possible. This is where Ashe’s experience within the ballet world and as a student of writing fuse brilliantly to produce a masterly evocation of the blood, sweat and tears involved that does not dodge technicalities, but weaves them naturally into the narrative. The intense rivalries and friendships that emerge in this setting are plausibly sketched; while the heroism and the pettiness, the superstitions and fierce loyalties all find their appointed place. If anyone wants to know what putting a ballet on truly involves this is now the go-to account to cherish, as relevant in the here-and-now as for its historical patina.

Lest this make the book seem more a social history than a novel, then I should assure readers that it does indeed also work well as a fluent and continuous engrossing narrative knitted together with many moments of psychological insight. The portrayal of the relationship between the twins is expertly done, demonstrating the depth of their bond and intuitive understanding, but also underlining their core differences in personality from which it seems then inevitable that ultimate divergence and separation must flow.

Equally compelling are the studies in obsessional behaviour, different in each case, that are the two leading male characters. And behind the portrait of the shoemaker is a fascinating evocation of the work and processes involved in creating ballet shoes. This might on the face of it seem fairly arcane stuff, but the descriptions of the real-life firm, Freed of London, based off St Martin’s Lane, lend to the story the same kind of vivid embodiment and statement of the importance of craftsmanship as does the cobbling of Hans Sachs in ‘Meistersinger.’

If I have one criticism it would be that occasionally there is just a bit too much fine descriptive scene-painting to be plausible as the viewpoint of a character caught up in the throes of action. But this is a minor cavil in a first novel of notable flair and distinction that does a great service to the art form it seeks to celebrate and cherish.