First staged in 1976, Death and the King’s Horseman is a fictionalised retelling of events that took place in Nigeria in 1946 following the death of the King of Oyo, in particular the duty of the King’s Horseman, Elesin, to commit ritual suicide at the time of his master’s burial. This being the 1940s (Soyinka adjusts the date slightly so that the play takes place in wartime), a complicating factor is the presence of the British as Nigeria’s colonial rulers, who (in the form of District Officer Simon Pilkings) regard the custom both as barbarous and as a potential occasion of unrest. However, Soyinka stated in his Author’s Note that the play should not be regarded as staging a ‘clash of cultures’; instead its focus is very much on Yoruba culture and cosmology, the vibrancy and sophistication of which are celebrated even as they experience a moment of crisis.

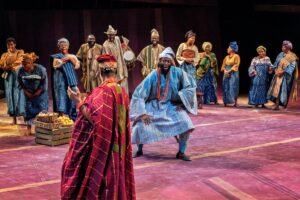

This staging is a co-production of Sheffield Theatres and Utopia Theatre, who ‘aspire to be the UK’s leading voice and producer of African theatre’ (Director Mojisola Kareem, programme). Just as Soyinka’s script foregrounds Yoruba culture through its entensive use of stories, riddles and myth, so the production asserts the vitality of that culture through dance, song, music and textiles. The opening of the play is set in the market, on a stage designed to echo the bright robes worn by the performers; the cast is augmented by a Community Ensemble who, far from merely making up the numbers, are crucial to the effect of the production. Notwithstanding strong performances by the principals, to me the market people felt like the heart of the play, an embodiment of collective identity with the potential to transcend the errors and weakness of more prominent characters. As for the principals, Wale Ojo embodies Elesin with supple charisma, combining haughty pride and a firm sense of his ancestral duty with wit, humour, and relish for the world he has to leave behind. Kehinde Bankole as Iyaloja, the Mother of the Market, modulates from dignified acceptance of Elesin’s abuse of power to contempt for his subsequent failure. As Simon and Jane Pilkings, David Partridge and Laura Pyper make the most of lines whose stiltedness is set up against the imaginative fertility of Elesin, Iyaloja and the Praise Singer (Theo Ogundipe), Partridge shifting between smug superiority and growing exasperation.

One aspect of Soyinka’s script that places particular demands on the performers is its incorporation of lengthy set pieces such as Elesin’s story of the Not-I bird, a manifestation of human fear of death, and the sequence of unanswered questions the Praise Singer asks of Elesin as he sinks into his ritual trance. The actors make good use of gesture and bodily movement to illustrate and punctuate moments like these, but for an audience not already familiar with the script Soyinka’s sometimes elliptical language can be a challenge. By contrast, the sequences that for me were most memorable were those where spoken language gave way to stage image, as when the women bring their grim burden onstage at the end of the play, and to music and song – the unaccompanied vocal performances in this production are stunning.

Death and the King’s Horseman was first performed only sixteen years after Nigeria gained independence from Britain; fifty years on, its analysis of colonial insensitivity has the potential to feel dated. However, in an age when Britain’s imperial past is still not widely taught in schools, it is no bad thing for that past to be reopened on stage (I should say here that as well as condescending attitudes, the play includes a racist epithet that elicited a noticeable intake of breath from the audience). Indeed, some aspects of the play, such as the Pilkings’ appropriation of Egungun masquerade costumes, have only gained pertinence amid controversy over the continued presence of Africa’s cultural heritage in museum collections elsewhere. But it would be a mistake to see this play solely as a response to empire; its importance, and its appeal to the playgoer, are in its verbal, visual and musical assertion of Yoruba culture, and its exploration of how tensions within that culture are experienced both at an individual and a social level.

Drama

By Wole Soyinka

Director Mojisola Kareem

Photo Credit Anthony Robling

Cast Includes Wale Ojo; Kehinde Bankole; Theo Ogundipe; David Partridge; Laura Pyper; Olesegun Lafup Ogundipe; Julius Obende

Until Saturday 8 February 2025

Running Time around 3 hours (including a 15 minute interval)