The 19th century was a time of profound upheaval for Jewish communities across Eastern Europe. Rooted in the rhythms of shtetl life — Torah study, close-knit family structures, and ritual observance — many Jews suddenly found themselves confronting new pressures: secularisation, nationalism, mass migration, and modern antisemitism.

Out of this tension emerged a remarkable literary and theatrical renaissance. Jewish writers, working in both Yiddish and Hebrew, gave voice to the complexities of tradition and change. Their works shaped modern Jewish identity and laid the foundation for one of the most beloved musicals of all time: Fiddler on the Roof.

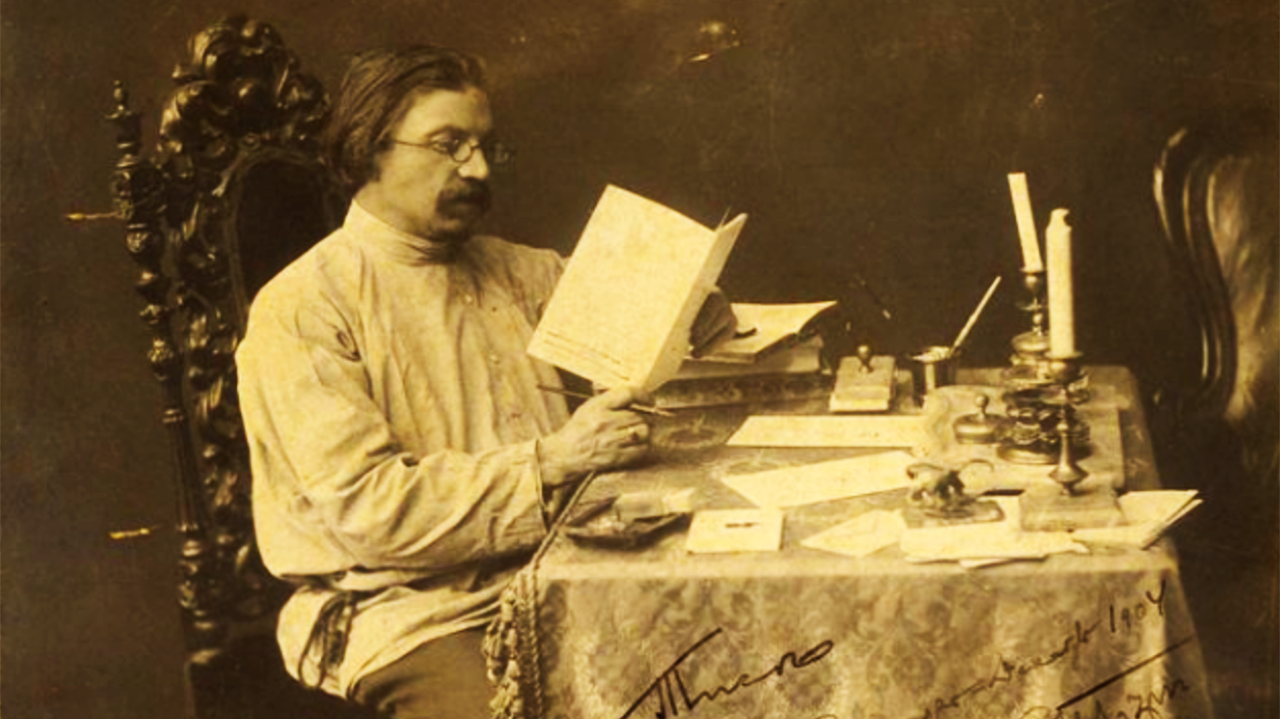

Abraham Goldfaden: Founding the Yiddish Stage

Among the most influential voices of this era was Abraham Goldfaden (1840–1908), widely regarded as the father of modern Yiddish theatre. His operettas, infused with folk melody and moral dilemmas, brought Jewish stories to the stage for the first time in a popular and accessible form.

Yiddish theatre quickly became a cultural lifeline. Audiences packed into makeshift theatres to laugh and cry through stories of rabbis, tailors, revolutionaries, and rebellious daughters. Writers like Jacob Gordin, Peretz Hirschbein, Sholem Asch, and Sholem Aleichem would follow, introducing realism, mysticism, and psychological depth to a growing dramatic canon.

Long before Fiddler on the Roof brought the world of the Eastern European shtetl to Broadway, Goldfaden was laying the foundations of modern Yiddish theatre. A poet, composer, and impresario, he founded the first professional Yiddish theatre in Romania in 1876, blending folk music, satire, and Jewish folklore into a genre that would flourish across Europe and America.

Two of his most influential plays — Di Kishefmakhern (The Witch) and The Two Kuni-Lemls — capture the very tensions that later animate Fiddler. In The Witch, Goldfaden critiques superstition and spiritual manipulation in the shtetl, contrasting age-old beliefs with the rationalism of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment). Meanwhile, The Two Kuni-Lemls offers a farcical take on mistaken identity and romantic freedom, as a modern suitor disguises himself as a pious fool to win a bride — poking fun at arranged marriages and inherited customs.

Goldfaden’s use of music as a narrative force was groundbreaking. His plays were filled with songs that ranged from comic to sentimental, echoing the klezmer-infused tradition that Fiddler would later popularise. Much like the score of Fiddler, Goldfaden’s music didn’t just entertain — it expressed character, belief, doubt, and change.

Sholem Aleichem: Voice of the Shtetl

Of all the writers of this era, none captured the voice of Eastern European Jewry more poignantly than Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916). His character Tevye the Dairyman, a milkman who talks to God and wrestles with change, became an enduring symbol of Jewish humour and resilience.

Between 1894 and 1914, Sholem Aleichem published a series of Tevye stories that chronicled a father’s bewildered love for his modernising daughters. One marries a poor scholar, another a revolutionary, another a non-Jew. Through Tevye’s witty monologues, we witness a culture breaking apart — with tenderness, sarcasm, and deep pain.

Sholem Asch: Breaking Boundaries

Among the writers who expanded the reach of Yiddish literature beyond the shtetl was Sholem Asch (1880–1957). Asch’s early plays and novels often explored Jewish life with rich psychological depth, but he also courted controversy by confronting taboo subjects — including interfaith relations and the experience of Jesus from a Jewish perspective.

His play God of Vengeance (1907), about a Jewish brothel owner and his daughter’s forbidden love, was both celebrated and censored. It became the first Yiddish drama to be staged on Broadway — and the first to trigger a public obscenity trial. Asch’s fearless storytelling opened new terrain for Jewish drama, bridging religious tradition and modern complexity. Though sometimes marginalised for his boldness, his legacy is one of literary courage and boundary-pushing imagination.

His play God of Vengeance (1907), about a Jewish brothel owner and his daughter’s forbidden love, was both celebrated and censored. It became the first Yiddish drama to be staged on Broadway — and the first to trigger a public obscenity trial. Asch’s fearless storytelling opened new terrain for Jewish drama, bridging religious tradition and modern complexity. Though sometimes marginalised for his boldness, his legacy is one of literary courage and boundary-pushing imagination.

From Shtetl to Broadway: Fiddler‘s Global Journey

In 1964, Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock, and Sheldon Harnick transformed these stories into Fiddler on the Roof. It became the first Broadway musical to centre an overtly Jewish story — and it struck a universal chord.

With hits like Tradition, If I Were a Rich Man, and Sunrise, Sunset, the show blended klezmer-inspired music with Broadway stylings. But beneath the charm was a story of exile and resilience. The musical ends not in triumph but in forced migration, with Tevye and his family leaving Anatevka — the fictional shtetl — for an unknown future.

The 1971 film adaptation, starring Topol, cemented Tevye’s status as a cultural icon. Today, Fiddler has been translated into over 20 languages and performed on stages around the world — from Tokyo to Tel Aviv, Johannesburg to Warsaw.

The Score as Storyteller: A Barbican Revival

The current Barbican Theatre revival — a transfer from Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre — brings new emotional depth to this well-known tale. Directed with subtlety and restraint, the production reveals how deeply the score itself acts as narrator.

One of the production’s great strengths lies in the way the score reflects the emotional arc of the narrative, often before the characters themselves can articulate what they feel. The opening number, Tradition, bursts forth with bold, percussive rhythms and chant-like repetition. Its musical structure mirrors the rigidity of the world it describes — orderly, rule-bound, and seemingly immovable. Yet as Tevye’s daughters begin to challenge the traditions handed down to them, the music evolves. It becomes more introspective, more lyrically expressive, moving away from the collective toward the individual. This shift in musical tone mirrors the broader breakdown of communal norms and the rise of personal agency.

The characters themselves are rendered vividly through musical language. Tevye’s soliloquies — If I Were a Rich Man, Tevye’s Dream — are half-sung, half-spoken, blending the rhythms of Jewish liturgical chant with theatrical storytelling. They become musical monologues, at once comedic and profoundly spiritual, dramatising his inner conflicts with sincerity and wit. Do You Love Me?, the understated duet between Tevye and Golde, uses hesitant phrasing and musical pauses to expose emotional distance. Their love, grown out of time and duty, rather than romance, is revealed slowly — as the melody softens, so too does their reserve. In contrast, Hodel’s Far From the Home I Love is lyrical and clear-eyed. The sparse orchestration leaves her exposed, mirroring both her isolation and her emotional resolve.

As the story darkens, the score becomes more fragmented and melancholic. The haunting Chavaleh Ballet, a wordless, swirling piece scored with ghostly strings and dreamlike choreography, gives us Tevye’s heartbreak in pure musical form. It is one of the rare scenes in musical theatre where music assumes the role of narrative. Later, Anatevka, the final ensemble number, offers no rousing farewell. Instead, its subdued, almost ironic tone captures weary resignation — the kind that accompanies forced departure and the knowledge that home, once lost, is not easily remade.

And yet, as beloved as the musical has become, it still softens the rawness of its source material. In Sholem Aleichem’s stories, there is no curtain call of cautious optimism. The arc of Tevye’s life ends in grief and dispersal. His daughters are lost to intermarriage, death, or distance. Golde dies. A pogrom wipes out what remains. Tevye is left a solitary figure with a cart and a road, wandering with no destination — his world disintegrated beyond repair.

The current Barbican Theatre revival seems to return to this darker origin. It sheds sentimentality for something more reflective and emotionally stripped back. Dry wheat borders the stage. A suspended wheatfield looms overhead — a symbol of abundance that will never be gathered. The iconic fiddler, usually perched on a rooftop to represent the delicate balancing act of tradition, appears only briefly at the start. After that, he walks beside Tevye — a shadow-like presence, a living metaphor for memory and inner tension.

Then, near the end, the fiddler disappears — and the melody is taken up by Chava, the daughter who marries outside the faith. Suspended above the stage within the wheatfield, she plays the familiar theme not on a violin, but on a clarinet — an instrument so central to klezmer, so expressive of breath, longing, and reinvention. It is a striking decision. Chava, once cast out, is now the bearer of the musical legacy. Her clarinet is not simply a substitution; it is a transformation. The melody survives — not because it is preserved intact, but because it has changed.

A Legacy in Words and Music

While Fiddler on the Roof has become a cultural touchstone, it is just one branch of a much larger literary tree. Writers like I. L. Peretz, Mendele Mocher Sforim, andSholem Asch chronicled Jewish life in its philosophical, mystical, and political dimensions. Many of their works, too, have found new life in translation, onstage, and in contemporary reinterpretation.

But it is Tevye — with his shrugging wisdom, his impossible choices, and his broken-hearted faith — who has become the global face of the 19th-century Jewish imagination. His story, born in Sholem Aleichem’s pen and carried through generations of musical and theatrical innovation, continues to resonate.

The world Tevye knew has vanished. But his voice — and his melody — echo still, carried forward in song, in story, and in the quiet persistence of memory.

At the Barbican Theatre until Sat 19 Jul 2025