Death of a Salesman is one of Miller’s most popular plays. I’ve had the benefit of seeing it twice: the first time was at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre with Antony Sher as Willy Loman. I think both performances have been greatly successful. Death of a Salesman maintains such an attraction because we are still saturated in the ideology it picks apart. The play touches on perennial issues about capitalism as Willy chases his cherished fantasy.

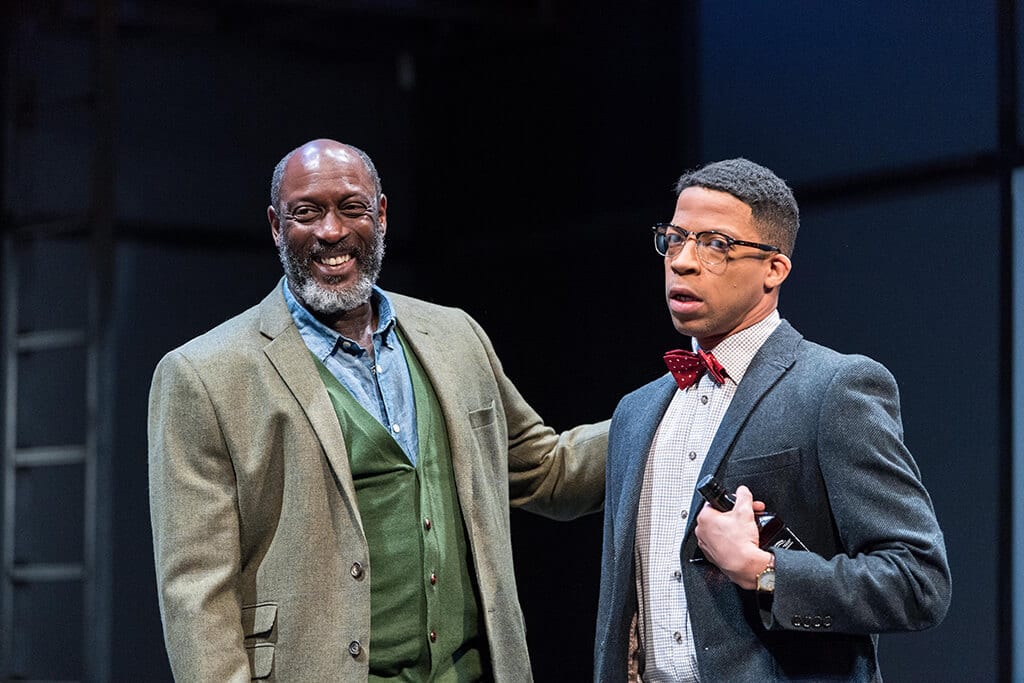

The narrative follows a family of four as they gather together: Willy (Nicholas Woodeson) and Linda (Tricia Kelly), and their two sons Biff (George Taylor) and Happy (Ben Deery). The couple are initially glad to see their boys return to the nest, but this elation does not last. The brimming potential of the past has run dry. Biff was once a hopeful Adonis-like football player, but he flunked school and suffered as his neighbour Bernard (Michael Walters) toiled and prospered. Happy was once eager to please his father, but he is clearly the less favoured son; he has become hardened to this over the years. Times are indeed bleak: the discovery of rubber pipe in the basement reveals Willy’s suicidal impulses. If death by gas inhalation is being flirted with, then Loman is truly a troubled man. To top it all off, the image of his deceased brother Ben (Michael Mullen), an intrepid explorer who made his fortune in the mining industry, plagues his stressed mind. Willy is entranced by the illusion of a diamond in the dark; it promises escape.

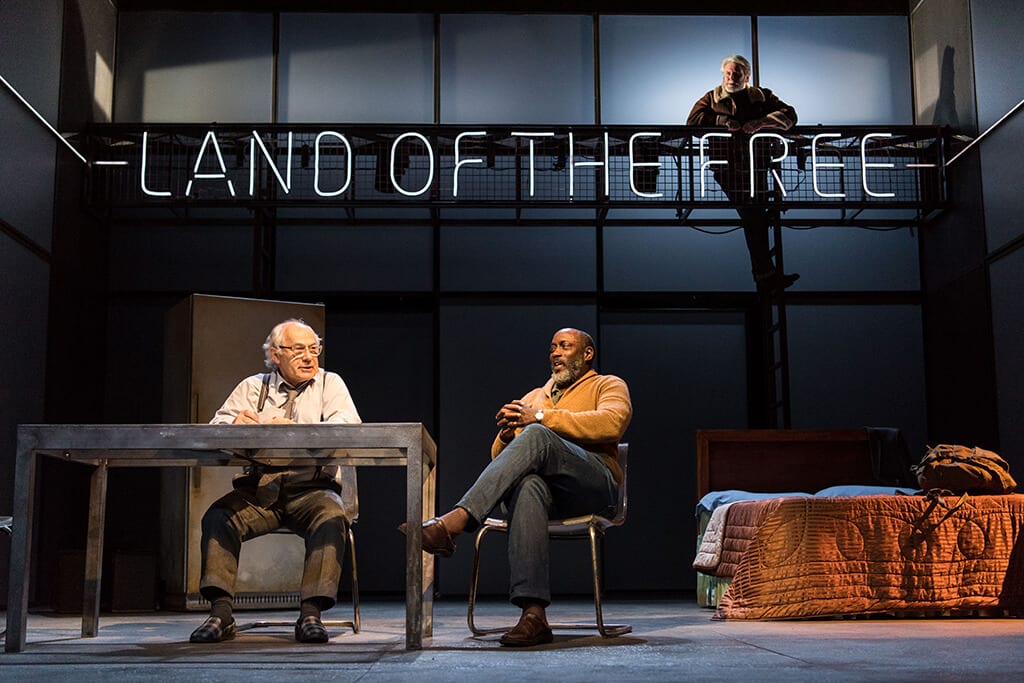

The worst aspects of capitalism are confronted in this play. There seems to be a never-ending stack of bills to address, which Linda keeps tabs on in her black notebook. But Willy can’t go to his boss Howard (Thom Tuck) for assistance. Howard has no sympathy for Willy’s exhaustion: the cold fact of ‘business is business’ does not accommodate senility. If you can’t rake in the goods, then you’re out of a job. In the background there is insistent neon lettering: ‘LAND OF THE FREE’. It shows how desiring profit is hardwired into the American consciousness, but Willy can’t understand that respect does not enter the equation. The characters like Howard thrive in New York because they are tigers in the wilderness. But Willy is no saint: he has his transgressions. Woodeson’s portrayal of a modern Lear is impressive. He exhibits contentment in a docile smile, paranoia with his darting eyes and anger through his volcanic ranting and raving.

The past bleeds into the present: nostalgia is a powerful force in Willy’s tired head. Seeing history through rose-tinted glasses is dangerous, since not relinquishing his dream is ultimately lethal. But it’s understandable why he’s so connected to the past, given that his current state is pitiable in its abject dreariness. He has developed a walrus-like paunch as he struggles with the endless asphalt stretches of his interstate commute. There is something of a poet in Willy and Biff as they attempt to leave the misery of a grey metropolis. However, the sun-drenched farms and grassy pastures of the West are a long way off.

As the end approaches, the situation accelerates into despair. In a bizarre move to promote nature versus the city’s steel and glass, Willy purchases some seeds to plant near his house. He petulantly kicks around soil like a distraught gardener. The fact of his unemployment, delusions and failure is insurmountable. He cannot resurrect the verdant world, those two majestic elms cut down to make way for sprawling tower blocks, as the weight of constant change crushes him; the effort for the American Dream cannot be sustained. He disintegrates like a doomed comet.