Emma Rice is a wonderful example of a ‘marmite’ director, whose productions are either greeted as startlingly original interventions that make you look at familiar works in a wholly new way, or heavy-handed interventions that wrench tone and story in unwelcome and undeserved, even inauthentic, directions. This is her first venture into opera, and while this work is robust enough to survive rough handling with many of its virtues intact, there are many points at which more respect for the original would have paid dividends.

Offenbach’s satirical operetta on the Orpheus and Eurydice myth admittedly does need some carefully judged decisions. It exists in two very different versions, and choices need to be made as to what to include and leave out in both dialogue and music. But what needs to survive is charm and lightness of touch and neither of these is in evidence for the first half hour of the evening or indeed for much of the finale set in Hell. Instead, Rice feels obliged to invent a ponderous back-story to explain the fact that in this version Orpheus and Eurydice are glad to be rid of one another. Charm only enters and didactic irrelevance exits, when the music insists on it with Pluto’s seduction aria with bees in a field of wheat. And at the end Rice insists that the shadow of #MeToo hangs heavily over the famous Galop Infernal or Can-Can. It is not clear to this reviewer that this frothy confection can bear the weight of so much ideological freight, or that it is necessary given that the figures of fun and bearers of negative reputation in this work are always the lecherous, sensation-surfeited gods, not the humans. The message is already there.

There are two aspects though that save this production from itself. Firstly, Rice’s approach really does bear dividends in Act Two, with a Beverley Hills swimming pool standing in for Mt. Olympus and all the sybaritic antics of gods on display. The rearrangement of the materials into a series of rapid-fire patter songs in the Gilbert & Sullivan style shows off the expert witty lyrics of Tom Morris to best advantage; and the director does not play around too much with the tone – a succession of superb satirical self-portraits brilliantly carried off by the singers allows the cynical brilliance of the writing to show through consistently. The lavish costumes, brilliant blues and whites of the set, and a pseudo-balletic chorus decked out in white balloons shows us rather than tells us that it is all about keeping up appearances and that the answer to everything lies ‘all in the optics.’

The other saving grace is the strength of the singing and acting which is uniformly crisp, nimble and technically skilful. This work offers much more for Eurydice than for Orpheus and Mary Bevan is fully up to the demands, whether in voice, dance or acting. Rice’s determination to turn the character into simple angry defiance of her fate does not help, but the bravura of the performance carries all before it. Bevan can well look after herself! Ed Lyon as Orpheus makes the most of the limited opportunities he has to establish his character, and sings his demanding arias with as much panache as he is allowed. He is ably supported by transgender baritone Lucia Lucas, who makes a very plausible London cabby voicing the views of ‘public opinion’ from a very real London taxi – this time a zany but apt directorial updating.

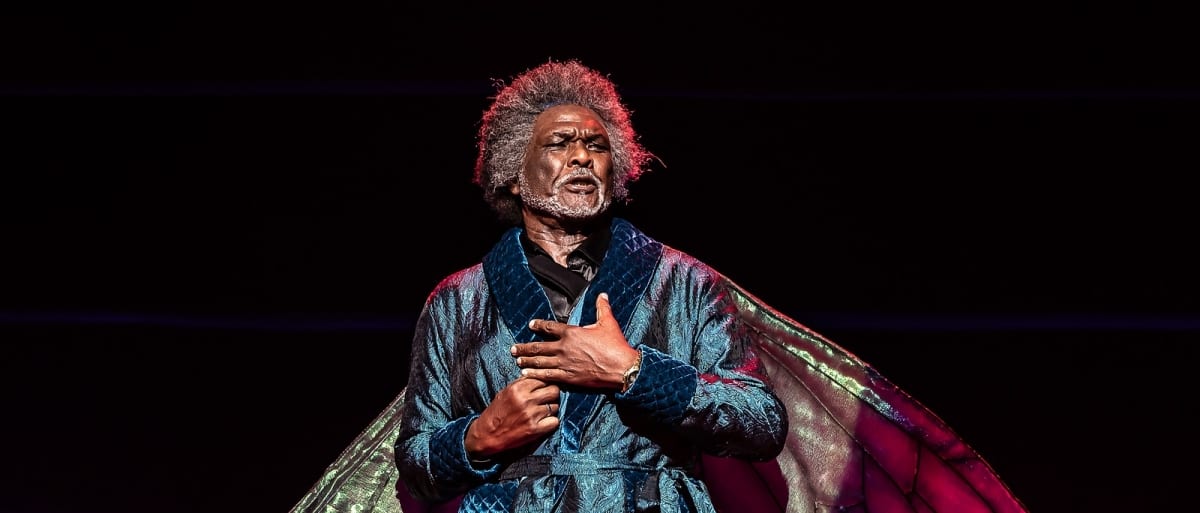

The most enjoyable work of the evening comes though from the superb roster of singers lined up to play the gods. All have their vocal show-off moments, but the two stand-out performances are from Willard White and Alex Otterburn, as Jupiter and Pluto. The latter cultivates exactly the right kind of rakish charm that is elsewhere in short supply in this production, full of knowing innuendo and plausibility; and the former catches the correct blend of sleaze and gruff, steely authority needed to depict a figure who is more ‘mafioso’ boss than detached deity. Alan Oke deserves a special mention for a fine comic turn as Pluto’s drunken and lecherous assistant, John Styx.

The glamorous sets by Lizzie Clachan manage to be showy and easy to manoeuvre between scenes: Hell is particularly well-conceived as both a seedy peep-show and a party extravaganza, successfully retaining the tone Offenbach intended. Lez Brotherson’s costumes make the right nods towards the Paris of the ‘Belle Epoque’, while also referencing the 1950s as the era of repression on earth from which everyone seeks to escape down below. Sian Edwards finds the pools of lyric interlude that lie amidst the mayhem, but still works up a storm with the orchestra in the sections that require it. As always here the chorus do a superb job in acting as well as singing very demanding material. And the special effects are, well ..special.

So the final verdict has to be a mixed one. The effervescence and unbridled satire is there to be sure, and this is a totally enjoyable evening. But it should not have to fight so hard against the director’s search for extraneous meaning. Ultimately the opera has to be performed on its own terms, not as a critique of itself.