A new play by an emerging young playwright is always of interest. I especially liked the premise behind Amman Paul Singh Brar’s Punjabi Boy of focusing on a young, second generation British Punjabi who was more attracted to French language and culture, than to either his British or Sikh backgrounds. However, despite the premise, this wasn’t a comic celebration of how an outsider found the means through an unexpected interest to challenge the assumptions and limitation of British and South Asian culture and how they consequently came into their own as an assertive individual – as in Bend It Like Beckam or The Buddha Of Suburbia. This is instead a study of passivity, a diary of a fragile, sensitive nobody who wants to be a nobody, not struggling to be somebody, and as such it arguably doesn’t lend itself to very successful drama. While Diljohn Sidhu does his best to emphasise Gary’s charm and sensitivity it is exceedingly hard to make the character really three dimensional as his core motivation is by its nature elusive.

The play’s structure also needed attention as I couldn’t see why there was an interval in such a short play and the play sometimes slowed to a crawl due to long, expository speeches when more action and pace would have worked better. Sometimes it sounds like a novel rather than drama. Avita Jay’s Kulli, a modern Punjabi girl provided a feisty, confident performance and the scene where she ditched Gary was one of the few where the play really seemed to come alive: the dialogue and stage action were sharper and more credible and there were none of the long expository speeches. It was a shame in fact their relationship didn’t work out, if Gary could have opened up there were places for them to go to emotionally. In contrast, I found Suzanne Kendall’s ‘stage Frenchwoman’, Aurelie, unconvincing and her accent seemed like she was channelling ‘Allo ‘Allo. Surely a play about a man studying and living in Paris should have given us a fuller, richer picture of French life and culture? This play might as well have been about Gary studying in Croydon as little use was made of the Paris setting.

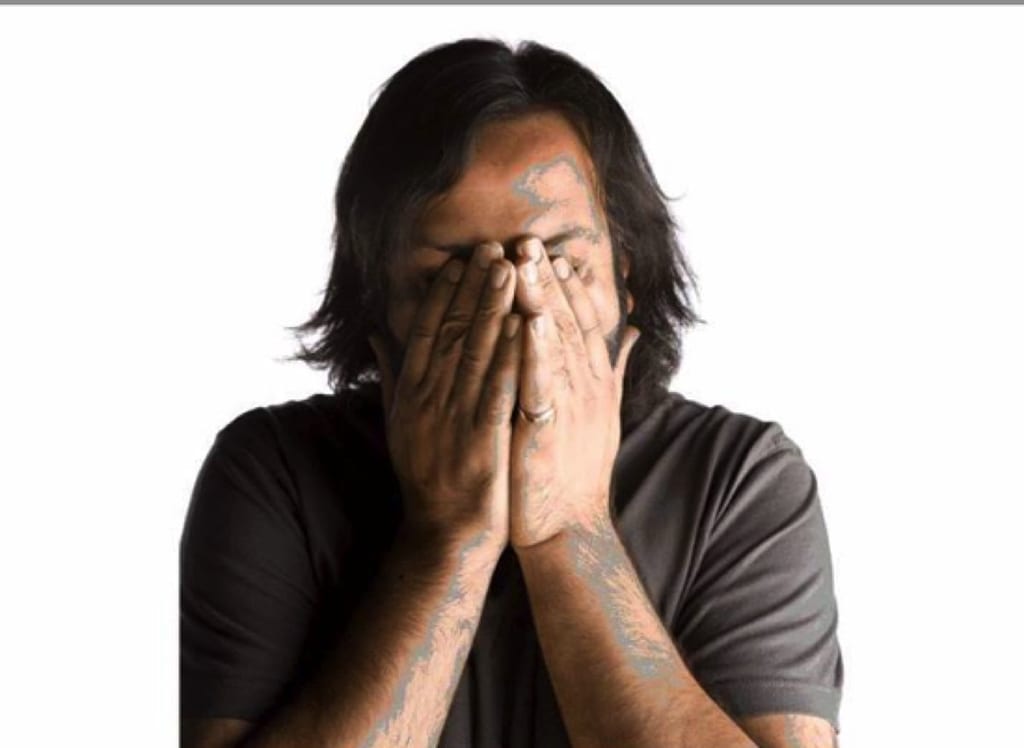

At heart the central problem is that protagonist Gary is not just a man without a voice – significantly he cuts his tongue during his final row with Kulli to indicate how all his anger is turned inwards – but a centreless, passive figure who doesn’t seem to want a voice. Happy with neither his Punjabi nor British backgrounds, even his attraction towards France seems inexplicable. Heroic failure with plenty of black comedy can be very powerful – think of Napaul’s Mr Biswas – but in this case it is hard to feel genuinely sympathetic to a protagonist who seems so mired is self-loathing, ennui and impotence.

Speaking to his close friend Raj – forcefully played by a solid Amint Dhut – we are itching for Gary to take on Raj’s rampant misogyny, his abhorrence of western female freedom and his narcissistic glorying in a very male ideal of Sikh culture. But instead, all educated Gary can do is repeat a scene from the beginning of the play where he himself had been racially bullied about his own Sikh culture while at his private school. Gary is still incommunicative and adrift between cultures: the play ends on a deliberately sour note sounded for this man who never was.