The Book of Judges devotes three chapters to the story of Samson. The composer, Camille Saint-Saëns, and the librettist Ferdinand Lemaire explore only the final chapter of the three in this opera. Samson’s heroics against the Philistines have all taken place before the opera starts. Samson is driven by his duty to his people, the Hebrews, and his insatiable desire for the alluring Dalila, a Philistine femme fatale. Delila is driven by hatred and revenge.

The Chorus, directed by William Spaulding together with the orchestra Royal Opera House conducted subtly and expertly by Antonio Pappano, creates a memorable musical experience. It is from the chorus’s opening scene through to the heroic singing of Samson the audience is enthralled.

Dramatically and musically Act I is predominantly an oratorio. The operatic drama is thinly drawn but powerfully sung. It was Saint-Saën’s initial plan to write an oratorio, a large-scale choral work based on a biblical theme, but the librettist and poet Lemaire suggested an opera, and Saint-Saëns enthusiastically embraced the idea. The result is an amalgam that is both magnificent, and not entirely reconciled within the operatic form.

The location is Gaza. The Hebrews beg their god, Jehovah, for relief from their bondage to the Philistines. Samson, their leader, rebukes them for their lack of faith. The Philistine commander, Abimélech, head adorned in gold, appears and is killed by Samson. The Hebrews rejoice in powerful and pious Gregorian chant.

The High Priest to the Philistine god Dagon appears and curses Samson’s prodigious strength. This is the prelude to Act II where the real drama slowly commences, reaching a crescendo in the final act.

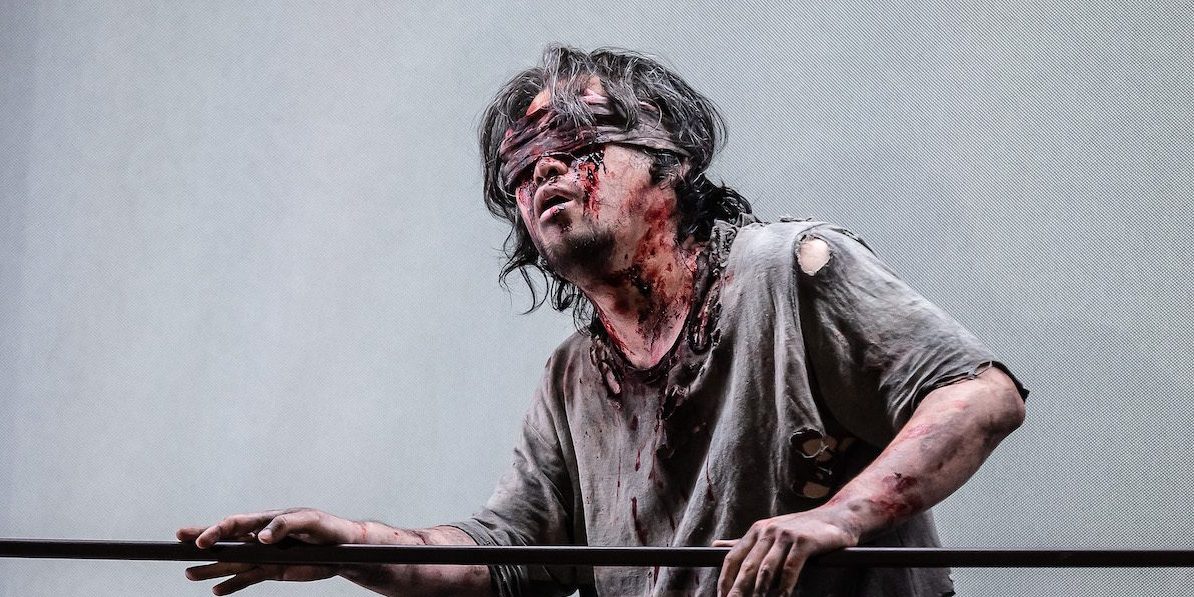

Saint-Saëns’s Samson is insecure and hesitant, succumbing quickly to Delila’s seductive, yet monotonous dance. Seok Jong Baek’s Samson has a voice that is nothing short of opulent. In the final dramatic and heroic act, he grows in stature.

Elina Garanča’s Dalila is granted full range to demonstrate her talents as a scheming seductress. She is a restless and somewhat aggressive and agitated Dalila, consumed by the desire to avenge her people. Garanča, a dramatic mezzo-soprano, has a deep and dark tonal range that beautifully articulates the depth of her character’s emotions.

Lukasz Goliński’s High Priest is initially baffling as he appears dressed in military regalia rather than religious garb. He offers a powerful and authoritative performance – his singing is firm and rich in tone and delivery.

Goderszi Janelidze’s small but important role as the Old Hebrew, Samson’s Rabbi, is vocally impressive, but dramatically, incomprehensible. He is projected as a blind man led by Samson, as a man in need of a physical crutch. This seems rather bizarre, and probably an attempt by Richard Jones, the director, to hint at what is to happen to Samson for not heeding his Rabbi’s advice.

Dagon, the Philistines’ god, is a red-nosed clown of sorts, holding gambling chips and slot machines on either arm, while the Israelites are more stayed in their tradition, brandishing prayer books in self-preservation. The scene in which two Philistines burn a small white T-shirt with the star of David on it made uncomfortable viewing, underscoring that the age-old undercurrents of antisemitism still stubbornly persist.

The famous Bacchanale with its oriental music and dance, heightens the cruelty of the Philistine’s victory over the now blind Samson, before the climactic finale.

The set, designed by Hyemi Shin is minimalist and simple, yet effective. The costume by Nicky Gillibrand is monochrome for Samson and the Hebrews but gaudy in texture and colour for the Philistines.

This is a difficult opera-oratorio to stage. The team at the Royal Opera House offers an imperfect, yet magnificent evening of this ancient story, translated into a modern drama.