This, the latest offering in the Almeida Theatre’s ‘Greeks’ series — which has been a brilliant success with engaging adaptations of Greek tragedies and a series of incisive talks and events on ancient Greek dramatic and poetic culture — is a live, non-stop reading of Homer’s Iliad, involving sixty readers sharing the performance of the twenty-four book poem, the longest and some would argue the greatest in the Western tradition.

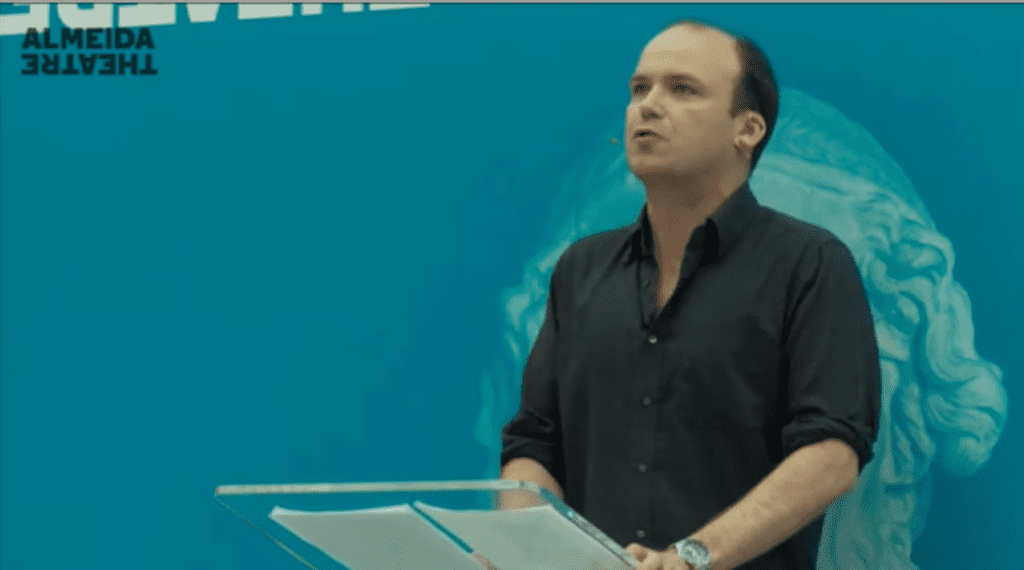

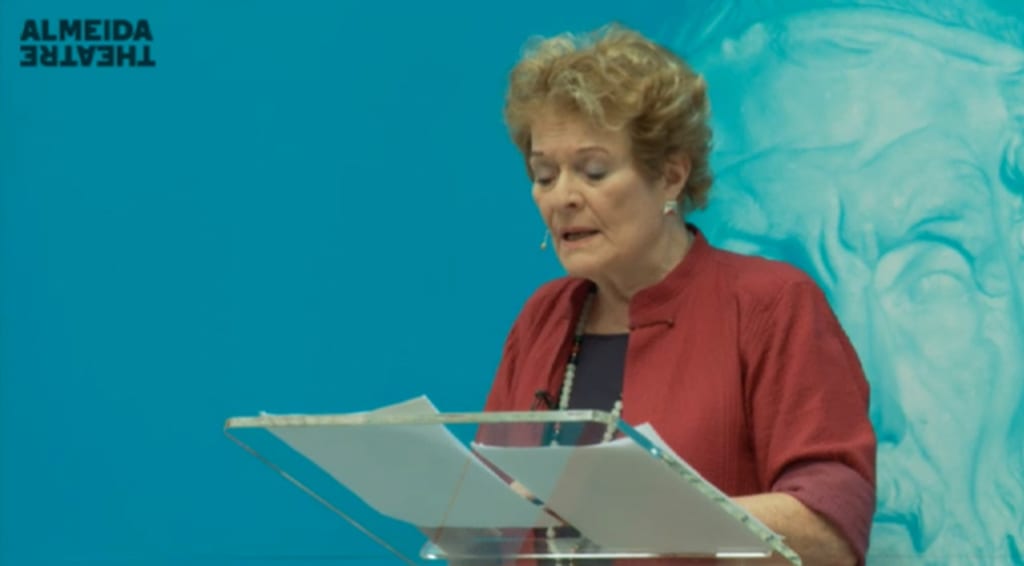

The reading begins in the Great Court at the British Museum at 9am, where benches are arranged before a podium, a microphone and television screens showing live tweets keeping audience members up-to-date with the action of the narrative, and continues until shortly before 8pm when the performance shifts to the Almeida Theatre in Islington, North London, where it finishes at around 11pm. The performance is designed for audience members to come and go throughout the day, though some staunch supporters are there from dawn until late at night. For anyone who cannot make it to the venues, the reading is also broadcast through live stream on the Internet.

The poem recounts several days’ fighting in the last year of the ten-year-long Trojan war and has as its protagonist Achilles, the greatest warrior of the Greeks whose rage at his treatment by his comrade Agamemnon leads him to withdraw from battle, threatening the success of the Greek army, and then, upon the killing of his closest companion Patroclus, to re-enter battle and take vengeance on the Trojans for Patroclus’s death. Without Achilles’ superior fighting force, the Greeks face decimation by the Trojans; with Achilles’ help the battle is turned back in their favour.

Eighth-century BC audiences of the poem would have listened to it recited, probably over the course of several days feasting, accompanied to the music of the lyre; the written form in which the poem has come down to us seems to have been a late amalgamated record of the oral, memorized versions of the poem in circulation in Greece in the Archaic period.

The Almeida’s twenty-first century offering is clearly a long way from the original Homeric audience’s experience – no meat and wine was served for a start, and this is Fagles’, admittedly wonderful, English translation; but also, in Archaic Greece it is likely that there was just a small number of professional bards circulating reciting the poem, and, crucially, the Almeida’s version did not include a musical accompaniment.

But, listening to the poem read out aloud intensely focuses the audience on its power. The poem was designed to sound interesting, full of rich visual images and narrative patterns which can help the listener who lacks page numbers or chapter titles to follow the narrative. For anyone already familiar with the poem, this reading also brought attention to some of the finer details of the poem that may be missed in reading. Its repetitions and transitions between scenes and interludes make much more sense as part of an ongoing reading, working rather like mental breaks for the listener without the performance having to actually stop.

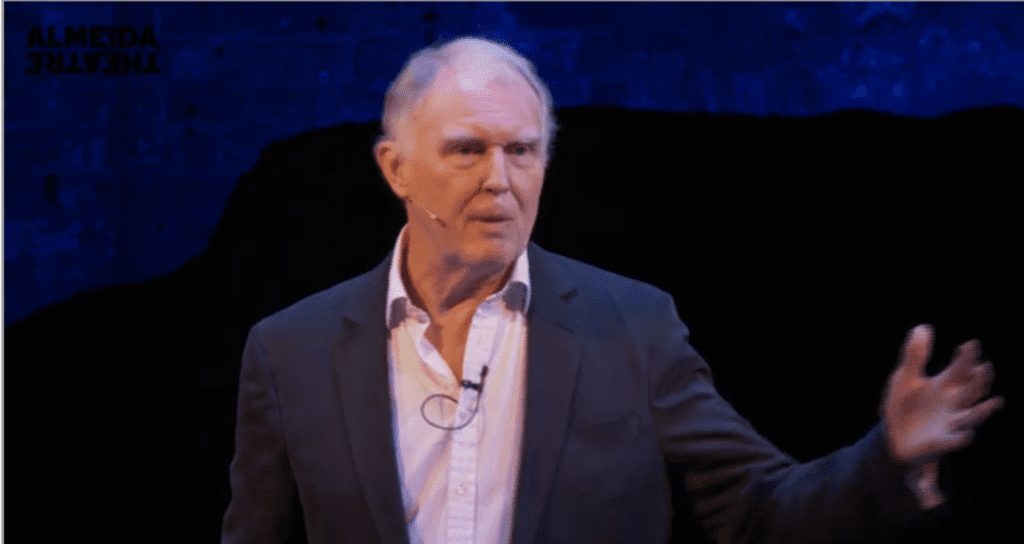

The Almeida’s performance brought the images and rich details of the poem to life brilliantly, and you could say that whatever may have been lacking in music of the lyre was made up for by the great variety and interest of the voices of the readers.

Most powerful of all was the intimacy and simplicity of sitting with other audience members listening attentively. A reading, more than an acted drama, gives each audience member more space to conjure up their own imaginative battlefield, lion-like Achilles, grieving sea-nymphs and golden dawns, all alike and unlike, common and individual.

As with the Almeida’s recent production of Aeschylus’ Oresteia, the emphasis was put firmly on audience participation – in the case of the Oresteia the theatre was turned into a court room and the production built to a climax which asked the audience to judge the guilt or otherwise of the protagonist. With this reading of the Iliad, the audience, a more constant presence than the readers themselves as they listened to more of the poem than each reader read, held the performance together by listening.

What a pity that this is such a rare occasion; please, Almeida, do it again!