With a portentous title like “The Truth”, one might expect a searing drama in this latest outing from the author of The Father, the play for which Frank Langella just won the Best Actor Tony in New York. But Zeller likes to surprise, and he certainly has, with this crackling, clever, little soufflé just opened at Wyndham’s Theatre in London’s West End. It’s a witty, joyous 90-minute sprint through a domestic minefield of infidelity and misplaced outrage. Think “Pinter meets Moliere”.

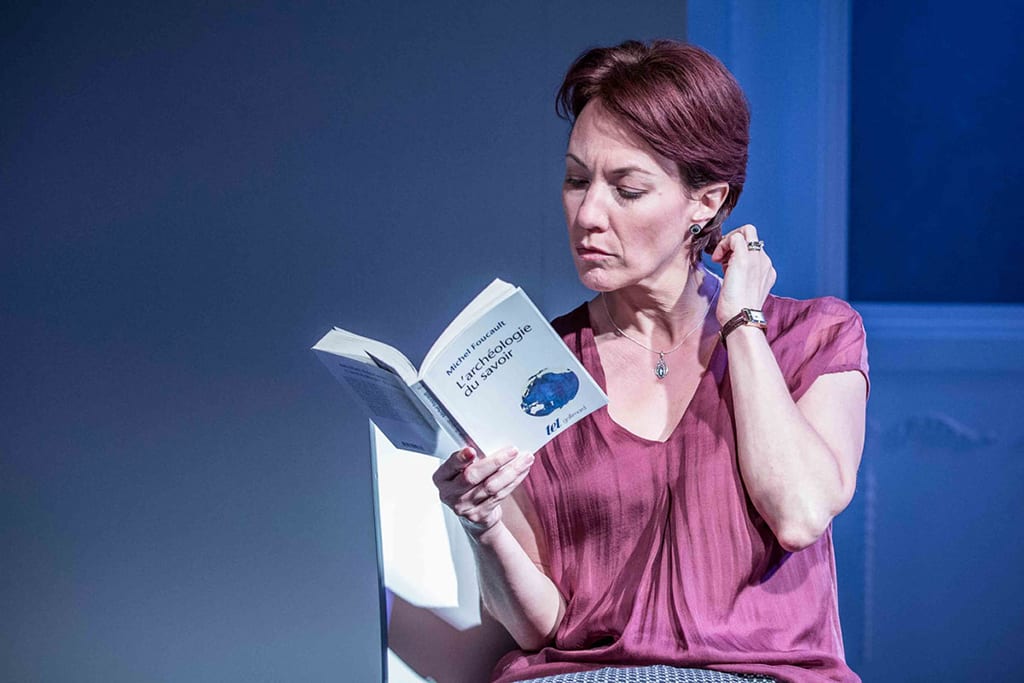

The action starts in bed. We meet Michel, a middle aged businessman in a pressure cooker of his own deceit (played perfectly right to the exact boiling point by Alexander Hanson) now in a critical passage in a months-long affair with his best friend’s wife. Alice (played with a cool clarity by Frances O’Connor, both in her sense of fun and growing guilt), is ready to have things evolve one way or the other in the relationship. She raises both the ideas of getting away for a whole night together for once and also the idea of telling their respective spouses all. This rather standard-seeming set-up becomes the foil for all the ticklish machinations to come in what is ultimately a bedroom farce of the mind.

Rather than turning solely on who discovers whom, Zeller artfully flips and twists our expectations about who knew what when. It’s very much the same central premise Pinter uses in his excellent Betrayal. But Zeller expertly and wittily extrapolates it further into a kind of multi-dimensional chess game of denial. The pressure mounts (and the audience gasps and laughs) because this is all among couples and friends who actually do love each other–enough to lie for each other’s emotional protection from…the truth.

Robert Portal is so self-assured and inscrutable as the best friend and tennis partner Paul that we constantly lose track of which way is up. And Tonya Franks as Michel’s wife Laurence brings a grounded vulnerability that ultimately strikes some of the most truthfully human notes in the evening.

Designer Lizzie Clachan’s set seems strangely spare and generic at first–with a few hundred dollars’ worth of white IKEA furniture. But as the quick-paced scenes flip from location to location, we come to appreciate the ease with which we mentally project the different settings onto the scaffolding provided.

It’s all so well executed, we can barely quibble with a thing. Zeller relies a little self-consciously on characters saying “what?” in rhythmic disbelief. O’Connor does not seem to have made quite real to herself that she is a doctor, with specific patients that have personal histories and demands on her. But it hardly matters. The comedic coils and hammers and valves are in full working order. Zeller has mastered the form.

Does The Truth reveal something new about human nature, about the inclination to dissemble and maintain appearances? Perhaps not. It’s a vein that has already been successfully mined by Moliere, Feydeau, Mozart, Pinter. Cosi fan tutti after all. But the real truth is, it’s awfully fun to come back to it, especially when done so well.