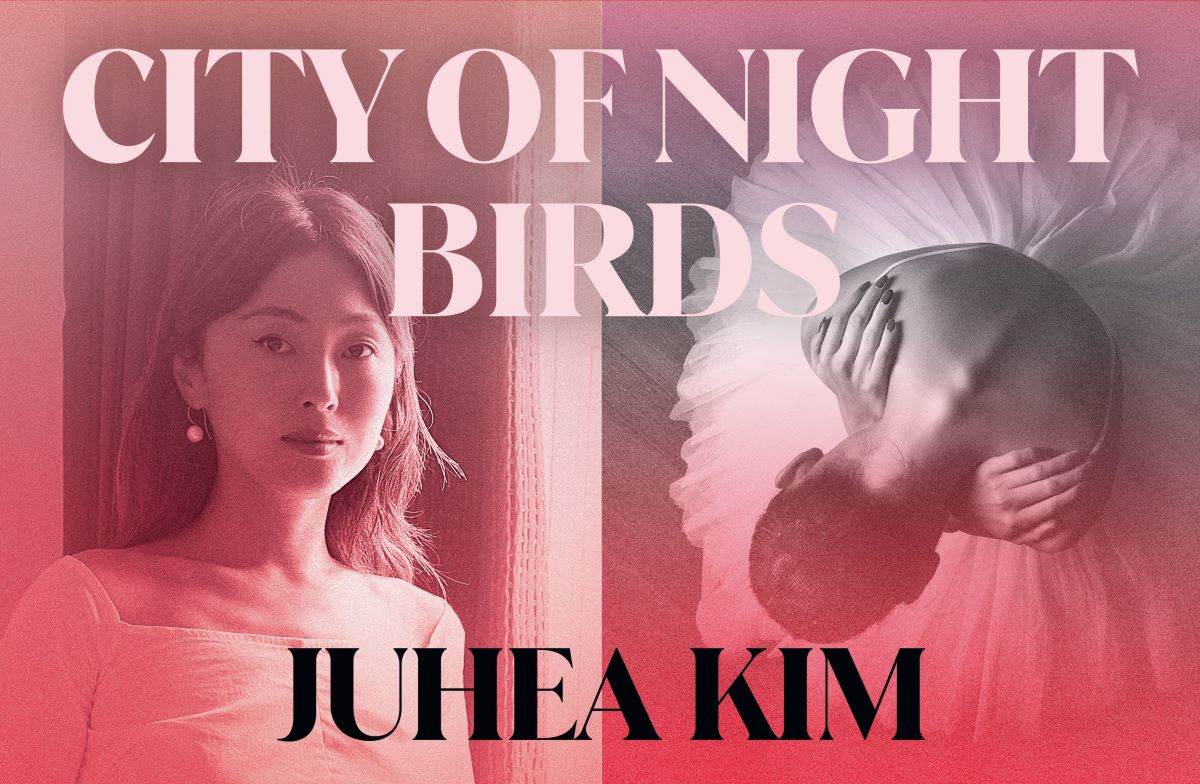

This is Juhea Kim’s second novel, and it is both a technically accomplished and highly accessible, compelling read. The story focuses on Natasha Leonova, an established Russian ballerina and the challenges she faces, both personal and professional. We meet her when she is at low ebb, sidelined after a mysterious injury, and burdened by addictions, but with a sudden tantalising opportunity to revive and return. This narrative unfolds in counterpoint with her personal relationships with two male dancers, Dmitri and Sasha, and in retrospect as we learn about the struggles of her early upbringing, and complex engagement with her parents.

This is a genuine page-turner and I would not want to inhibit the reader’s enjoyment by elaborating on the plot. Rather let me try to summarise its core general strengths that should impress any reader, but especially one intrigued by the emotionally intense, politically charged complexities, of the world of ballet.

The first quality that stands out is the evocative and graceful elegance of the scene setting. The novel’s location moves across St Petersburg, Moscow and Paris, and Kim describes each city with accuracy and successful integration into the story without resort to obvious stereotypes. The second feature that strikes the reader is the easy assimilation of the technicalites of classical ballet into the narrative. Readers often think they will find the intricacies of ballet intimidating, but here you are taken the heart of the emotions involved in the steepest technical challenges, while still receiving a clear sense of exactly what efforts and sacrifices the training and rehearsal involves. It definitely helps that Kim is herself a dancer for whom dance is still part of her regular working life. The third aspect of the writing that really succeeds is the one that is perhaps most difficult to bring off consistently. The balance between forward propulsion and explanatory or revelatory flashback is expertly maintained. This is a superbly structured and organised book, though you never see the scaffolding on which it is arranged.

Many, if not most, readers will be taken by the romantic sweep of the love story involved, and I would not want to detract from that for a moment. But it is also a novel about artistic obligations, both to yourself and to your public. There is a remarkable monologue in which Natasha examines all these issues in detail – what she owes to herself and what she owes to her art – that is one of the best meditations I have read on these perennial themes in many years. This is entirely in keeping with the Russian artistic context, where a high social salience and moral seriousness about the arts is axiomatic. You can sense the background influence of Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita not far away; and the quotations from and references to Akhmatova and the values she represented are integral to the book, rather than decorative.

If I have a criticism of the novel it is that sometimes there are at points just too many themes and issues in play; but it would be churlish to resent this richness for long. It is rare to find a novel that succeeds so well simultaneously on so many levels. It deserves to be enjoyed and cherished therefore by the widest range of readers.