“They’re no angels,” actress Anna Popplewell tells me wryly, speaking of Solange and Claire, the two maidservants at the centre of Jean Genet’s dark dream of a play, The Maids, which opens at Jermyn Street Theatre this week. Based on real murders committed in Le Mans in 1933 by Christine and Léa Papin, live-in domestic staff who killed their employer’s wife and daughter, the production, directed by Annie Kershaw, explores destructive societal hierarchies and their psychological effects on the individual. As Popplewell explains, Genet’s play asks with radical provocation, “what people do when they’re pushed to extremes […] when they feel trapped, how they cope with that in terms of light and darkness.”

Jean Genet was well-versed in extremes. He was the poet laureate of the gypsy-hearted, a vagrant saint. Before he was a playwright, he was the black-uniformed orphan who had resorted to petty thieving. He grew up in the claustral walls of French prisons, measuring out his life in the books housed in their libraries. The beginnings of one of his great works, Our Lady of the Flowers (1943), was written on the back of paper bags in the absence of a notebook and rewritten from memory when the original manuscript was confiscated by prison guards. That Genet wrote for the stage at all is a miracle; he rarely went to the theatre, a cultural establishment that, to him, was decidedly bourgeois and at odds with his insurgent spirit.

Anna Popplewell, who is taking on the role of Solange, one of Genet’s great anguished outcasts, will be inhabiting his world of transgressive and sadomasochistic fantasy for the next month, first at the Jermyn Street Theatre and then at the Reading Rep. How would she describe Solange? “I keep coming back to the word heaviness with her.” Confronted with the burden of looking after her ailing sister Claire, and forced by economic necessity into a form of submission that is slowly eroding her sense of self, “she’s desperately wishing to find something in her life to keep her going and sustain her,” she says. It’s an intriguingly refreshing piece of casting. After all, Popplewell is known as the child star of the Narnia chronicles whose Susan Pevensie enchanted the imagination of every child of the noughties. Yet as I speak to Popplewell, her affinities with Genet become obvious—she too is driven by a spirit of discovery and exploration.

A highly successful early acting career was, she admits, “a happy accident”. Her casual participation in a Saturday drama group, encouraged by her parents in order to build confidence, soon led to her being scouted by an agent. Film sets beckoned. The wardrobe opened. But Popplewell’s mind kept roaming. She attended Magdalen College, Oxford, to read English, where, incidentally, C.S. Lewis had been a tutor and fellow. “It was only really when I went to [Oxford] University that I considered acting as a profession because I’d always just done it for fun […] it was always such an adventure.”

It was at Oxford that she first fleetingly encountered Genet’s play. Reading it again was like reaching a hand into a box of tricks. “You’re constantly having the rug pulled out from under you: there’s the play within a play, there’s lots of deception,” she explains. But much of her attraction to the project was meeting this challenge. Popplewell was interested in figuring out “how to observe and create that bewilderment for an audience whilst being incredibly specific and knowing exactly what you’re doing as an actor.” Furthermore, the play seduced her with its thorny lyricism; Martin Crimp’s exquisite text – the translation chosen by Kershaw in this production – is like encountering barbed wire covered with rose bushes. As Popplewell puts it, “it’s the juxtaposition of the beautiful language with the darkness of the play’s content that makes it so striking for so many people”. Since rehearsals of The Maids have progressed, she tells me she has come to realise just “how spiky and jagged the shape of it is” but also how “tightly woven”. It’s a reflection of Genet’s diagonal perspective: his acute sense of the adamantine structures that keep systems of oppression in place, matched by his ability to imagine, through the witchery of writing, the holes necessary to tear through them.

Of course, for Popplewell to truly understand the play’s twilight criminal world – a place dark enough to assuage consciences but light enough to enact crimes – she has turned to researching “modern murder cases”. Exemplifying the rigour with which she approaches her craft, she states that “it’s been my job to work out the naturalistic trajectory of how that could happen to someone”. She cites former neonatal nurse Lucy Letby, convicted of murdering seven infants, and the school shootings in America as cases that had a profound effect on her. “I think I just was most interested in looking at […] cases today where someone who otherwise appears to be having a fairly average and functional life gets tipped into a more extreme event”. It’s a reminder to be more conscientious of the people around us. With consideration in her voice, Popplewell discloses an urgent truth: “One should always be open to the idea that people are dealing with something much more massive than you might realise”. “There’s so much hidden life, whatever your social role, that gets buried by society,” she continues. This radical attempt at sympathy was Genet’s gift to theatre. Before there were John Osborne’s angry portraits of working-class life or Samuel Beckett’s philosophical tramps, Genet made martyrs of the maids in the kitchen.

Solange and Claire find release from these circumstances through participation in theatrical roleplay. In their highly ritualised ceremony – referred to by Jean Paul Sartre as a “black mass” – maids can pretend to be mistresses; the submissive can be dominant. Hierarchies, Genet points out with serious facetiousness, depend upon no more than wearing the right clothes. Popplewell is deeply attuned to the psychological solace it provides: “It’s a routine […] there’s a script, there’s a rubric. As humans we seek comfort in ritual. The idea that there’s this sort of near-religious aim that they get to play and that it follows the same pattern every night, or almost every night, is really important to them.” It’s a comment that inadvertently speaks to the mystical nature of theatre itself.

And it was the stage, as well as vibrant young director Annie Kershaw and her talented cast, that drew Popplewell to this project. She had worked with Kershaw in 2023 on Hedda Gabler, the production that marked her theatrical debut. “I haven’t done a lot of theatre so for me it’s really exciting finding my feet on stage […] I’ve really learnt a lot from watching the other cast.” She describes Charlie Oscar, who plays Claire, as a “completely phenomenal actor”: “they’re so live […] it’s a huge pleasure to watch someone with a different sensibility, different skillset, work.” Carla Harrison-Hodge, who plays the Mistress, also receives praise for her work on “humanising” the role and gusto in performing what is a “real mic-drop of a part”.

The Maids may be Popplewell’s first time on stage in London, but she is certainly no stranger, having spent many evenings observing the flickering wisdom of performances and watching theatrical history unfold. As an actress, she tells me of discovering the “magic” in the theatre of “being the last point of transmission between a story and an audience”. “You’re not quite that on film or TV,” she explains; “you get chopped up and moved around [in the edit]”. And as an audience member? “I’ve always loved watching theatre,” she enthuses. “I felt that it was this great collection, going to the theatre. Rather than collecting stamps or Pokémon cards, that you’re adding to this bank of ideas and actors and designers and directors and visions.” She stresses its inestimable value outside the auditorium too; it is, as she eloquently says, a “wonderful mental resource to draw from and relate to.” Indeed, it is the portal to understanding hidden lives, the space for dreaming, as Genet’s characters do, of other existences.

THE MAIDS

By Jean Genet & Translated by Martin Crimp.

9 – 22 January 2025 – Jermyn Street Theatre

28 January – 8 February – Reading Rep Theatre

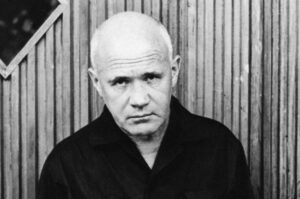

Photography by Steve Gregson