An interesting, yet traditional, reading of Mussorgsky’s masterpiece is presented at the Royal Opera House in the original (1869) seven-scene version, which plays 130 minutes without interval and without the subsequently inserted Polish Act and Kromy Forest episodes. This version, which is still fairly rarely performed, is considered to be closer to Pushkin’s original drama as well as Mussorgsky’s original intentions than any other version and its cast is almost entirely a male cast of soloists.

Let me make it clear – the 130 minutes feel like no time at all. With theatrical clarity, the orchestration, costumes and set carry the magnificent chorus and the largely fine, idiomatic performances by the cast on a journey where a troubled period in Russia’s history, unfolds through Mussorgsky’s libretto and music.

Miriam Buether’s impressive set and split-level staging, simple, yet effective costumes designed by Nicky Gaillibrand and Mussorgsky’s astringent orchestration under the baton of Antonio Pappano are anchored in Richard Jones’s concept of the opera; this production is set in no given period, but creates an ambience which somehow portrays or captures the essence of Mother Russia.

Those not familiar with the historical background – in a nutshell, after the death of Ivan the Terrible (1530 -1584), the grim memory of whom is often invoked in this opera, dies, Boris Godunov, his confidant, steps in to guide the future Tsar. Ivan’s eldest son, weak-minded and pious dies and the younger one, Dimitri, is assassinated. Rumour has it (which Pushkin, on whose account of Boris Godunov Mussorgsky relies for his libretto, accepts as true) that the murder was carried out at Boris Godunov’s behest. Like Shakespeare’s Macbeth, or Richard III, the audience is left in no doubt who is the usurper and the reasons for his demise and have little sympathy with his tormented conscience.

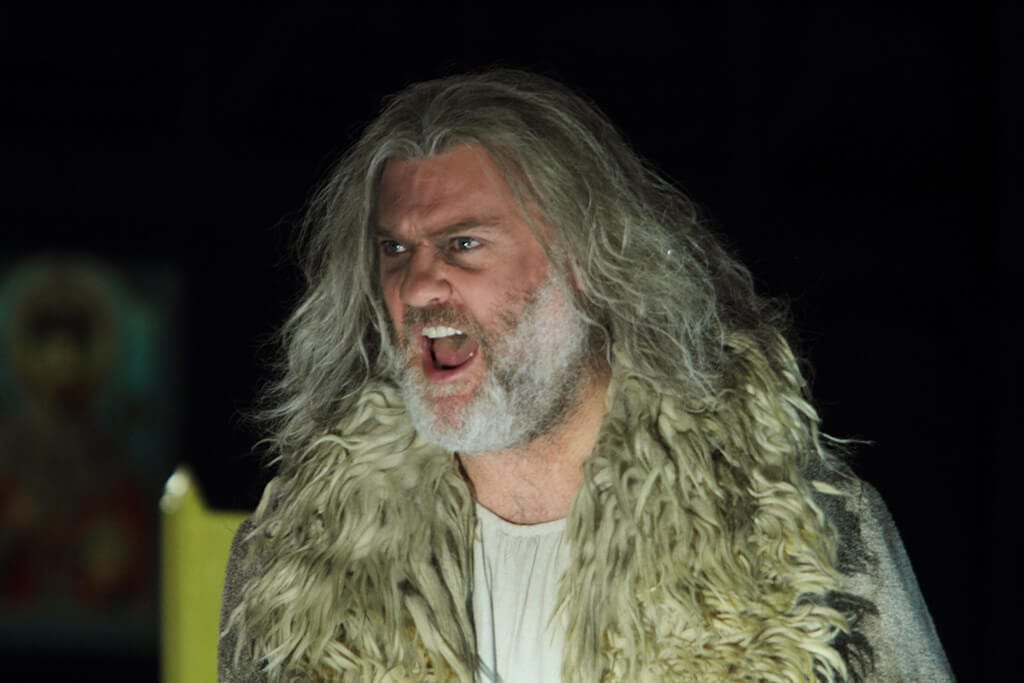

A large image of a spinning-top dominates a front screen. Once the lights dim in the auditorium, a child playing with a toy spinning-top is seen in the upper gallery while below, seated on a bench is the large figure of Bryan Terfel head down. Three figures, with their faces covered creep into the gallery, knife in hand and in slow motion re-enact the murder of the child, Dmitri.

The assassination scene reappears seven times in the course of the performance, reflecting Boris Godunov’s conscience, which is tearing him apart in each and every year of his seven year reign.

The Chorus staging, costume, choreography and singing create a complete theatrical and musical treat. This production conveys the change of mood of the drama and the characters, from obedience to menacing.

Richard Jones’s direction leans towards the main protagonist’s troubled inner world, which in turn, weakens the stature of Boris the Tsar. Terfel’s Boris is human and tender not always as domineering as this Tsar should be. He is physically towering but his bass –baritone voice although rich in tone fails to move. He is more sympathetic and vulnerable than tyrannical. His voice lightens as death approaches. Ain Anger sings Pimen, the Chronicler monk strongly with a hint of the youthful passions. Comic relief is at hand in the delightful Inn Scene with the inestimable John Tomlinson’s Varlaam. Andrew Tortise’s Holy Fool also introduces humour to a somber procession. Like King Lear’s Fool, he tells the Tsar the truth with jest. Boris pardons him for calling him a murderer and asks him merely to “pray for me”, which the Holy Fool refuses to do with a mischievous twinkle as he explains that the Virgin Mary will not permit him to pray for Herod.

This production is musically vivid, dramatic and in parts, exciting.