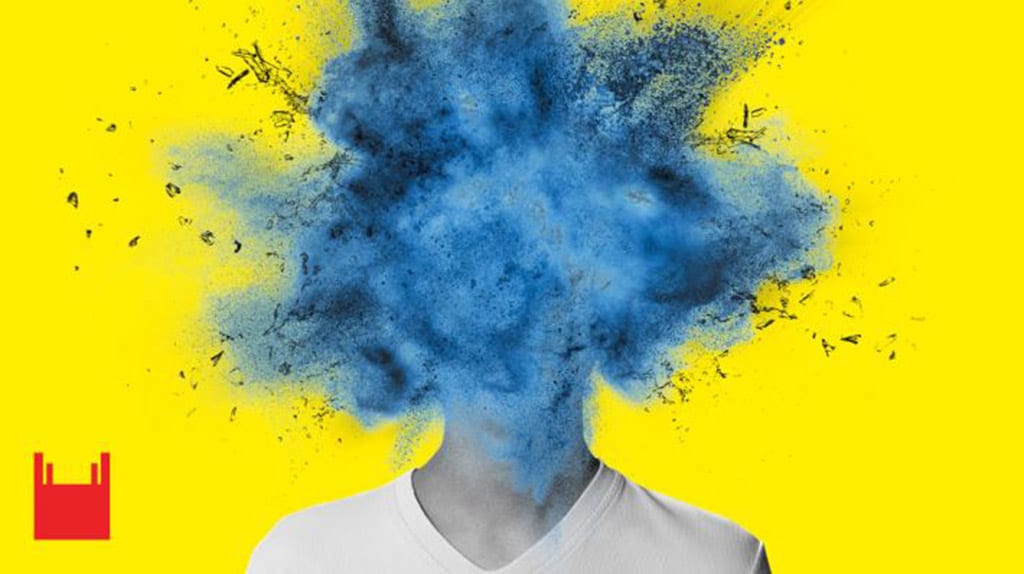

My brain isn’t broken, says a solitary teenager on stage. Life as a teenager isn’t easy; it’s confusing, frustrating and terrifying. But it is exciting, vibrant and electrifying at the same time. The Islington Community Theatre’s original production Brainstorm portrays the lives of teenagers perfectly.

The mad changes that an adolescent’s mind experiences, the complex and volatile relationships with our parents and the things we’d like to say, but can’t, are all creatively performed to a thoroughly engaged audience of all walks of life. Expectant mothers, to older people whose adolescent years seem very far away, to teenagers like myself, are all drawn in.

This production, which has been playing for almost four years with the same cast, is authentic and straight from the heart. The ten actors on stage tell stories of real experiences with passion and meaning. Ned Glasier, the director of Islington Community Theatre, spoke after the show about the selection process for young actors. He informed us that these talented teenagers were chosen not for their acting ability, but for their stories that they could tell. And in a way the performers weren’t actors at all; they were all teenagers of 14-18, like me, who struggle to tell their parents how they feel and know firsthand what it’s like to be a teenager. Any parent sitting in the audience would be reassured that it’s not just their child who locks themselves up in their room or who won’t talk to them like they used to.

This is possibly the most relatable play that I have ever had the pleasure of seeing. From the busy (and live!) WhatsApp group projected on to one of the cupboards on the set, to the agonising explanation to your mum of how to use the television remote when all you want is to do is just go upstairs and hide in your room, I felt like my life and the life of my friends was being acted out before me. But this time it is shown for an audience of adults, for them to see how we really feel behind the moping mask of adolescence.

And there is a lot more going on in the adolescent mind than you would expect. With 86 billion neurones buzzing around, our brains are not a ‘crap version of an adult’. There are more neurone connections than we will ever have again. Our limbic system is the main part of our brains that is not yet the same as a fully grown adult. We are more inclined to take risks as a result, and the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for the prevention of these actions, has less power. Brainstorm presents this information in a fun and imaginative way, providing illustrative examples for the audience to relate to.

Brainstorm is arranged in three ‘acts’. The first section is jocular in mood, with audience participation and frequent laughter from the entertained spectators. A sudden, crazy and reckless rave scene brings the comedy to an end. Demonstrating the wildness of a teenage party, the actors go mad on stage, with loud music blaring. The rest of the play has a more solemn feel. Portraying the restraint and anger of teenagers, the audience begins to sympathise with the previously upbeat actors. The parents are not demonised, rather presented as people who can never really understand us. And to a certain extent, this is true. They were teenagers once, but from their perspective as parents, it is hard to see life from our viewpoint. Despite all this anger and frustration that the teenagers on stage feel towards their parents, they still end on a touching note. Each of the ten actors holds up placards as soft music plays, dropping them one at time. On them are messages for their parents. ‘I can’t really say this to you but…’ reads one card, ‘I love you’.

The comic timing and wit of the actors is brilliant. It’s not often that adults acknowledge the life and laughter that teenagers bring to the room, but this showcases our best qualities. By the end of the performance the adults in the audience undoubtedly think more admirably of the youth’s value in society. The hilarious parodies by the actors of their parents is a light-hearted, but poignant portrayal of how our parents see us. After the show, co-director Emily Lim spoke about the main message of the play. Parents often cast their teenagers in their light, expecting them to be what they were or what they want them to be, because that is the only light they know. But the many lights flicked on and off by the actors during a moving part of the play about their dreams for the future, showed that there is no single light to cast on one’s child. They must choose which light to switch on. I was gripped and entertained.

If this play wasn’t ending on Saturday, I would say that every parent in the country should go to see this production, because they need to know what these actors told us authentically and powerfully: My brain isn’t broken. It’s just not the same as yours.