Tennessee Williams’ 1969 play, In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel is rarely performed, and after watching, I think there is some reasoning behind that. It is far from Williams’ best work. It feels like an early Williams’ drama, laying the blueprint for his future work. It comes as a surprise that it was written over twenty years after A Streetcar Named Desire. Whilst there are moments of interest, it feels clunky and confused, and the cast consistently struggle to get to grips with the script throughout this production.

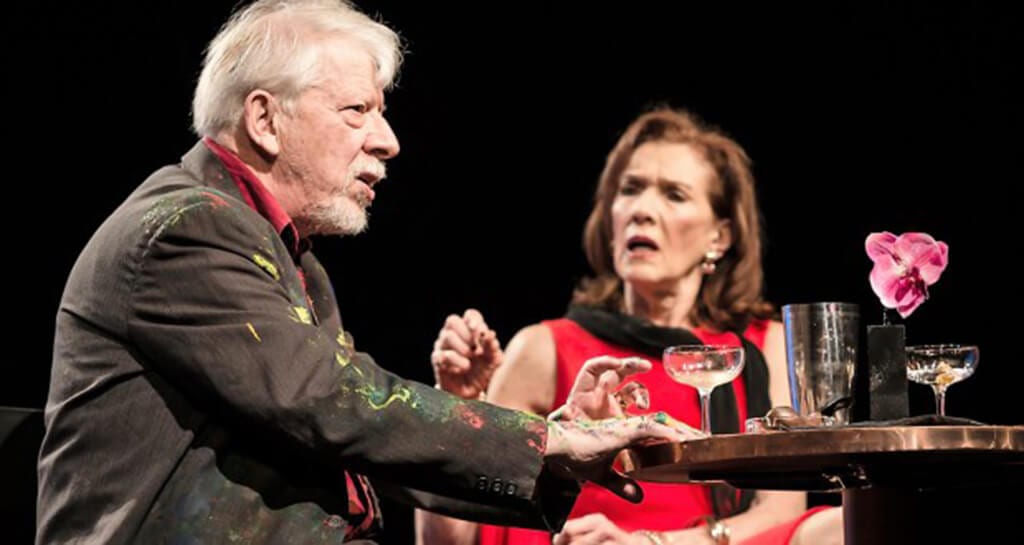

The drama unfolds, as its title suggests, in a bar in a hotel in Tokyo. We meet Miriam (Linda Marlowe) a frustrated, promiscuous, ageing American. She has travelled to Japan with her husband, Mark (David Whitworth), a successful artist. Mark is completely engrossed and tormented in his artistic project, to the point of insanity. Isolated from her husband, Miriam turns her attentions towards drinking and hopeless attempts to seduce the Japanese barman. The struggles of husband and wife run parallel to one another.

Robert Chevara’s production is upheld by Nicolai Hart-Hansen’s daring stage design. The bar is set on a steep, sloping stage, which is certainly the best talking point of the evening. Linda Marlowe’s portrayal of the frustrated Miriam is spirited, but she is inconsistent in carrying her American accent. David Whitworth struggles to connect with his role as her husband and troubled-artist, Mark. His movements seem calculated and a little over-done. A drama based solely in one room relies heavily on dialogue, which on the whole, does not come across fluidly. Interruptions are rarely well-timed. Nevertheless, the play offers occasional glimpses of comedy, which are welcomed.

In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel offers some interesting insight into Tennessee Williams’ body of work. He wrote the play after exploring Japanese Noh Theatre in the 1960s. This was an interesting move to make after the commercial success of a play like Night of the Iguana earlier in the decade. Chevara’s production is spirited, but I would save it primarily, for hardcore Tennessee Williams fans.