In the ferment of 19th-century Eastern Europe, amid the upheavals of empire, migration, and modernity, Jewish writers began to carve out a distinct literary tradition in Yiddish. Though long considered a vernacular tongue, Yiddish became a powerful medium for storytelling that reflected the joys, sorrows, and ironies of Jewish life in the Pale of Settlement. External literary traditions, particularly Russian realism and, to a lesser extent, English social novels, played a significant role in shaping the content and form of Yiddish literature. Yet, this tradition also evolved a unique voice, deeply rooted in Jewish life and experience. No writer embodied this synthesis more profoundly than Sholem Aleichem, whose character Tevye the Milkman stands as a symbol of cultural negotiation, humour, resilience, and loss.

Historical and Cultural Context

The 19th century was a time of profound upheaval for Jewish communities across Eastern Europe. Rooted in the rhythms of shtetl life—Torah study, close-knit family structures, and ritual observance—many Jews suddenly found themselves confronting new pressures: secularisation, nationalism, mass migration, and modern antisemitism. Out of this tension emerged a remarkable literary and theatrical renaissance. Jewish writers, working in both Yiddish and Hebrew, gave voice to the complexities of tradition and change. Their works shaped modern Jewish identity and laid the foundation for one of the most beloved musicals of all time: Fiddler on the Roof.

Abraham Goldfaden: Founding the Yiddish Stage

Among the most influential voices of this era was Abraham Goldfaden (1840–1908), widely regarded as the father of modern Yiddish theatre. His operettas, infused with folk melody and moral dilemmas, brought Jewish stories to the stage for the first time in a popular and accessible form. Long before Fiddler on the Roof brought the world of the Eastern European shtetl to Broadway, Goldfaden was laying the foundations of modern Yiddish theatre. A poet, composer, and impresario, he founded the first professional Yiddish theatre in Romania in 1876, blending folk music, satire, and Jewish folklore into a genre that would flourish across Europe and America.

Two of his most influential plays—Di Kishefmakhern (The Witch) and The Two Kuni-Lemls—capture the very tensions that later animate Fiddler. In The Witch, Goldfaden critiques superstition and spiritual manipulation in the shtetl, contrasting age-old beliefs with the rationalism of the Haskalah (Jewish Enlightenment). Meanwhile, The Two Kuni-Lemls offers a farcical take on mistaken identity and romantic freedom, as a modern suitor disguises himself as a pious fool to win a bride—poking fun at arranged marriages and inherited customs.

Goldfaden’s use of music as a narrative force was groundbreaking. His plays were filled with songs that ranged from comic to sentimental, echoing the klezmer-infused tradition that Fiddler would later popularise. Much like the score of Fiddler, Goldfaden’s music didn’t just entertain—it expressed character, belief, doubt, and change. Yiddish theatre quickly became a cultural lifeline. Audiences packed into makeshift theatres to laugh and cry through stories of rabbis, tailors, revolutionaries, and rebellious daughters. Writers like Jacob Gordin, Peretz Hirschbein, Sholem Asch, and Sholem Aleichem would follow, introducing realism, mysticism, and psychological depth to a growing dramatic canon.

Russian and English Literary Influences

The influence of Russian literature on Yiddish writers was profound and pervasive. The psychological depth and moral intensity of Tolstoy, the existential anguish of Dostoevsky, the satirical bite of Gogol, and the social consciousness of Turgenev left clear imprints. Many Jewish authors were educated in Russian schools or read widely in Russian, absorbing its literary techniques and thematic concerns. The Jewish experience—marked by persecution, spiritual searching, and societal marginality—found resonance in the dilemmas of Russian literary characters.

English literature, while geographically and linguistically more distant, gained prominence among Jewish emigrants to the West. Charles Dickens, with his detailed character studies and concern for the plight of the poor, particularly influenced Jewish writers in America. George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda (1876), with its sympathetic portrayal of Jewish identity and Zionist aspirations, marked a rare but notable English engagement with Jewish themes.

The Emergence of a Unique Yiddish Voice

Despite these influences, Yiddish literature forged a distinct aesthetic and moral sensibility. It was colloquial, intimate, and often tinged with irony. The genre developed through pioneers like Mendele Mocher Sforim, who used satire to critique Jewish society from within, and I.L. Peretz, who combined romanticism with a search for spiritual renewal. Mendele, considered the “grandfather” of modern Yiddish literature, created the persona of a wandering bookseller who offers both a critique and a reflection of Jewish life, helping to lay the groundwork for the modern Yiddish literary voice.

Sholem Asch, a later figure in this lineage, brought Yiddish literature into dialogue with broader humanistic and even Christian themes. His controversial works—such as God of Vengeance and his New Testament trilogy—pushed the boundaries of Jewish literary norms. Though sometimes marginalized for his boldness, Asch’s influence was lasting, and he is buried in London—a fitting symbol of the diasporic journey of Yiddish letters.

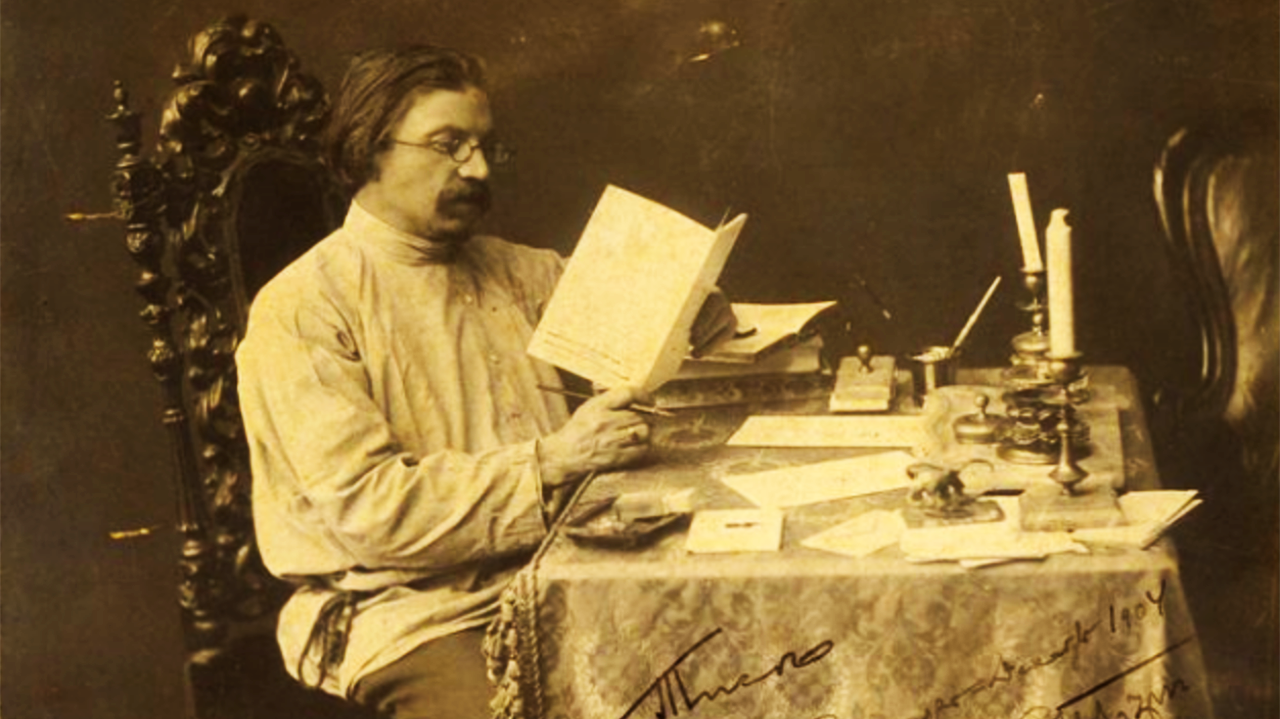

Sholem Aleichem and Tevye the Milkman

Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916) was arguably the most beloved and influential Yiddish writer of his time. Dubbed the “Jewish Mark Twain,” he brought humour, pathos, and psychological realism to stories of everyday Jewish life. His most enduring creation, Tevye the Milkman, first appeared in 1894 and continued to evolve until 1914.

Tevye is a poor milkman who speaks directly to the reader in a voice that is by turns philosophical, comic, plaintive, and defiant. He quotes scripture with ironic familiarity, philosophizes about fate and faith, and recounts the misadventures of his daughters as they increasingly embrace modern ideas and marry outside the traditional fold. Through Tevye, Sholem Aleichem gives voice to a generation wrestling with modernity, secularism, and the disintegration of traditional life.

What makes Tevye so compelling is his ability to oscillate between tragic insight and absurd humour. His monologues are rich with Biblical and rabbinic references, yet his worldview is deeply human and secular. Tevye is both a symbol and a person: a man trying to hold onto tradition while everything around him changes.

The narrative style—first-person, confessional, digressive—invites comparisons with Russian literary narrators, while the structure of the Tevye stories, as a series of episodic encounters with modernity, echoes the picaresque novel. Yet the texture of the work is distinctly Yiddish: rooted in shtetl idiom, communal rhythms, and Jewish theological dilemmas.

Sholem Aleichem’s choice to have Tevye speak directly to a silent listener—often understood to be a fictionalized version of the author himself—adds a metafictional layer to the narrative. This device echoes techniques found in Russian literature, notably Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground, where the narrator delivers a confession-like monologue to an imagined audience. Similarly, in Gogol’s Diary of a Madman, the protagonist’s descent into delusion unfolds through diary entries that simulate a personal, if unstable, communication. Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin also features a narrator who frequently breaks the fourth wall to address both characters and readers. Sholem Aleichem’s innovation lies in transposing this narrative intimacy into the Jewish world of the shtetl, infusing it with humour, irony, and cultural specificity. The result is a character who is both deeply self-aware and profoundly embedded in his communal context. Like Dickens—whom Sholem Aleichem admired—he crafts a world that is at once deeply personal and socially expansive. The adaptation of Tevye the Milkman to a musical, as Fiddler on the Roof has truly universalised Sholem Aleichem’s creation and emphasised its timeless character.

Sholem Aleichem directly influenced a wave of Jewish writers in Europe and America, including Isaac Bashevis Singer, who would go on to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Singer, like Aleichem, combined folklore, moral ambiguity, and wry humour to depict the richness and contradictions of Jewish life. The storytelling tradition Aleichem helped define became the bedrock of both modern Yiddish fiction and Jewish-American literature.

Yiddish literature of the 19th and early 20th centuries arose at a crossroads of empire and exile, shaped by external literary traditions but anchored in a uniquely Jewish experience. The influence of Russian realism and English social narrative provided tools for psychological depth and social critique, but the voice that emerged was unmistakably Yiddish: ironic, self-aware, steeped in tradition, yet open to change.

Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye exemplifies this synthesis. In him, we see not just a character but a worldview—a Jewish Everyman negotiating a world of shifting values and vanishing certainties. Through laughter and lament, his stories preserve a vanished world while speaking to the perennial human struggle to find meaning amid change.

While the literary Tevye ends his journey in solitude and uncertainty, the stage adaptation Fiddler on the Roof (1964) offered the world a way into that world of upheaval and endurance. The musical, drawn from Sholem Aleichem’s stories, transformed the intimate, ironic voice of Tevye the Milkman into a global symbol of diasporic identity and communal resilience. With its klezmer-infused score and Broadway stylings, Fiddler opened the gates of the shtetl to international audiences, introducing millions to a vanished way of life. But beneath the charm and music lies the legacy of Yiddish writers—storytellers who documented, critiqued, and preserved the emotional and spiritual landscape of Eastern European Jewry.

This essay, therefore, seeks not only to celebrate Fiddler‘s enduring appeal, but to point back to its deeper literary roots—to the pages where Tevye first walked, doubted, joked, and prayed.

Biographical Timeline

- Abraham Goldfaden (1840–1908)

Born: Starokostiantyniv, Russian Empire (now Ukraine)

Died: New York City, United States - Mendele Mocher Sforim (Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh) (1836–1917)

Born: Kapyl, Russian Empire (now Belarus)

Died: Odessa, Russian Empire (now Ukraine) - I.L. Peretz (1852–1915)

Born: Zamość, Congress Poland (then Russian Empire)

Died: Warsaw, Poland - Sholem Aleichem (1859–1916)

Born: Pereiaslav, Russian Empire (now Ukraine)

Died: New York City, United States - Sholem Asch (1880–1957)

Born: Kutno, Poland

Died: London, United Kingdom - Isaac Bashevis Singer (1902–1991)

Born: Leoncin, Poland

Died: Surfside, Florida, United States

Fiddler on the Roof at the Barbican Theatre until Sat 19 Jul 2025