Be prepared for a brief hour and 25 minutes of a totally absorbing, gripping and unsettling journey, when you take your seat at the Wyndham’s theatre to see this production of Florian Zeller’s The Father, winner of 2014 Moliere award for France’s best play.

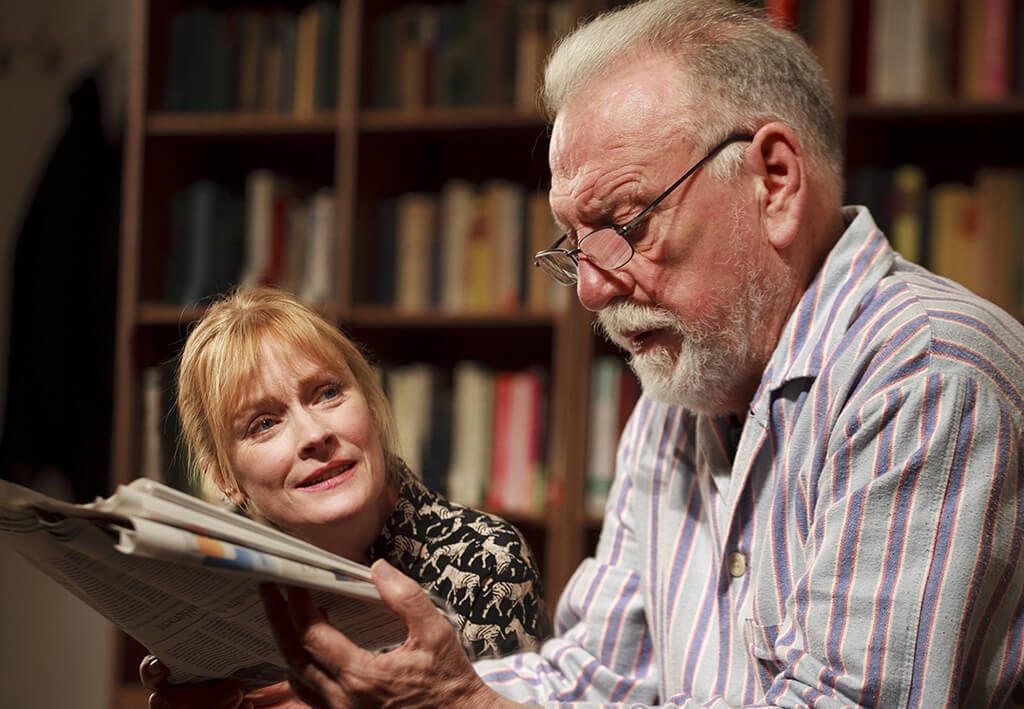

The story’s theme may sound depressing, but it is not. It is simple yet confusing. Andre (Kenneth Cranham), an elderly man with dementia struggles with time and space while his daughter, Anne (Claire Skinner), battles to balance her love for her father, the demands of his care and her own life and relationship with Pierre (Nicholas Gleaves).

The very title conveys intimacy, which goes beyond bystander observations; the shared memories, emotions and unspoken understanding between father and daughter, that are taken for granted, diminish in the face of the crippling dementia.

Zeller’s skilfully fuses physical reality with Andre’s state of mind. Andre’s eroding memory confuses events with thoughts and dreams and we, the audience, are drawn into the living room and are privy to wry comments, Andre’s flirts with one of the carers, who reminds him of his beloved daughter, Elisa, his accusations that another carer has stolen his watch, his repeated hurtful comments to Anne, his daughter, reminding her at every opportunity that she is not his favourite child. He cowers before male figures, Pierre in particular, who physically bullies Andre. But, does he really? We are never certain if what we see is what actually happens or are we shown the reality as seen through Andre’s befuddled eyes.

The room’s furniture diminishes gradually casting further doubts as to the location. Are we in Paris, in Andre’s flat or in London, at Anne and Pierre’s flat? When Andre asks “who exactly am I” one senses the pain of self-awareness.

James Macdonald’s brilliant semi-sub-plot he cuts the audience from the unfolding drama on stage, by flashing across the stage a pitch black shroud, akin to a TV screen, surrounded by light bulbs, like a mirror into which we can see nothing, or a picture frame with no picture but a solid black background, lasting a few long seconds, heightened by loudly played piano notes, reverberating like the screech of a damaged record. The transitions from these ‘dark’ moments, brilliantly mirror the progression of the disease in Andre’s brain, like a tidal wave that wipes out imprints of recent trails.

Christopher Hampton’s translation superbly conveys the humour and pain. Performances by all six actors are excellent. Cranham ‘s Andre is outstanding. He unravels a sympathetic yet not a sentimental man, one who is grumpy and funny, cruel and sweet, loveable and tiresome. He flirts with youthful charm, exposing something of the man he once was. Claire Skinner’s Anne, the daughter, wins over sympathy and understanding.

The ending of the play reminds me of a moving scene in Eugène Ionesco’s The Chairs, where the old man cries “where is she? My mamma.” which seem to join the absurd with the physical reality we live in.